‘The Ables’ series showcases ability in disability

November 1, 2019

Nashville-based author and CinemaSins YouTuber Jeremy Scott combines fantasy and reality in his book series “The Ables,” which follows a set of superhero teenagers who also have disabilities.

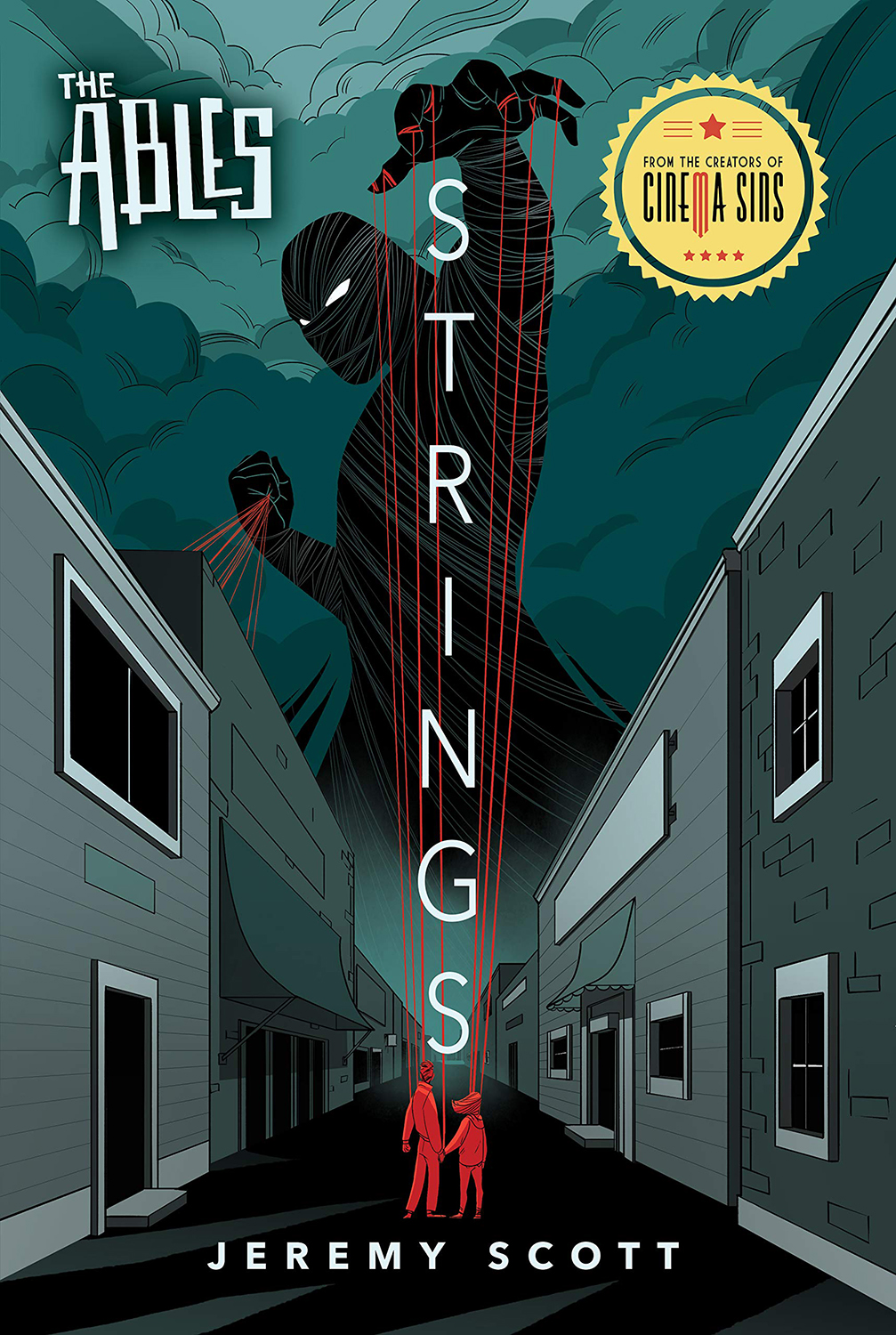

Released Sept. 24, “Strings” is the second book of his four-part series “The Ables” in which three superhero friends with disabilities are on a quest for acceptance after being put in a superhero special education class.

Because the protagonist, Phillip, is blind and has the power of telekinesis, his question becomes, “‘How do I move things with my brain when I can’t see anything?’” Scott said.

Phillip’s best friend Henry is paralyzed but has the power of telepathy, and uses his powers to send images from his eyes to Phillip’s brain.

The third friend in their group is Bentley, the mastermind of the friend group, who has a form of cerebral palsy and is hyperintelligent, Scott said.

Scott, who is 50% deaf in both of his ears and has anxiety and depression, said there is a lot of himself reflected in his characters and the story.

“Society looks at someone with a disability and says, ‘Look how good you’re doing,’ and stops there,” he said. “I don’t think the world looks at a kid in a wheelchair and wonders if he might want to be a creative writer.”

He said there are existing stories with characters who are disabled, but there is not enough representation. Scott said he hopes it is something society changes.

Sandy Murillo, a producer in the media center of The Chicago Lighthouse—an organization that assists individuals with disabilities with job security—grew up completely blind. She wished there had been representation in the media for people who shared similar characteristics as her.

“Sure, I met a few blind role-models here and there,” she said. “But it would’ve been awesome to have maybe a favorite character on TV or in the movies or something … that I could maybe relate to.”

Murillo said people have reacted to her blindness as if it is no big deal, but most of the time, when people realize she is blind, they are hesitant to interact with her.

In the past, people have raised their voices at her because they associated blindness with deafness. And recently, she said people unnecessarily assumed she needed assistance while giving a presentation when she did not ask for it.

“I don’t think they meant anything wrong … they were just trying to be helpful,” Murillo said. “This and other examples just show how ill-informed people can be about, not just people with blindness, but people with other disabilities.”

However, there are things that people can do to support those with disabilities without assuming they need help, she said. Simple things like offering to read a menu out loud, making ramps more accessible and asking before petting a service animal are easy ways to make individuals with disabilities more included in society.

Dominic Calabrese, retired senior vice president of public relations at The Chicago Lighthouse and adjunct professor in the Communication Department, said after working for the organization, he has gained a greater appreciation and understanding of everything individuals with disabilities can do.

Calabrese said he uses people-first language—which puts the person first, then references their disability—when talking about someone with a disability as a sign of respect.

“People are defined by their humanity, not their disability,” Calabrese said.

Scott said the series still has a third and fourth addition yet to come. The next book will follow the friends through college and adulthood.

“You get to decide what your identity is,” Scott said. “And who and what you’re going to be in this world.”