Riley Malcomson, a sophomore double major in theater and ASL-English Interpretation, is a first-time voter registered in Illinois.

To prepare for the upcoming election on Nov. 5, Malcomson is watching both CNN and Fox News in an attempt to avoid biases. Being skeptical of misinformation, Malcomson said she tries to fact-check what politicians say.

“I try not to take everything at face value,” she said. “Being an ASL interpreting student, one thing we have to do is interpret for meaning. I see how politicians will say something, but what do they mean? Or they’ll say a statistic, but what’s the background of that?”

Young and first-time voters like Malcomson are preparing to cast their ballots through a host of resources available to help people prepare for the election. Non-partisan organizations like Columbia Votes, Chicago Votes and the League of Women Voters Chicago all assist voters looking for answers to their election questions.

“Anything that makes it easier and demystifies the process, I think is helpful,” Evan Segelke, a senior film and television major, said.

This is the first presidential election for Ahmed Ankolkar, a first-year acting major and registered voter in Ohio. He has his go-to sources, like the news agency Reuters, but will also fact-check information. “If sources aren’t really posted, I try to see if there are other sources I do trust that say the same thing.”

Besides news and online educational resources, some students said they also reference what they learned in U.S. government courses from high school.

Anastasia Wynecoop, a first-year music major and registered voter in Illinois, reflected on the government class she took at her high school in Indiana.

“It was a really eye-opening class, but it was not exactly engaging with political beliefs and everything like that,” Wynecoop said.

Eric Hansen, an associate professor and the graduate program director for political science at Loyola University Chicago, said a “well-designed curriculum that promotes student engagement” and participation positively correlates with voter turnout. Mandatory statewide civics exams also push young people to the polls.

“We should expect these programs to be most helpful in encouraging turnout among people who don’t learn about politics or voting from their families and communities outside of schools,” he said.

Illinois has a civics mandate for grades nine through 12. The mandate states that two years of social studies are required. The history of the U.S. or a combination of U.S. history and American government is required for at least one year. Additionally, “at least one semester must be civics,” which should help high school students “acquire and learn to use the skills, knowledge and attitudes that will prepare them to be competent and responsible citizens.”

In July 2021, the Illinois legislature passed a measure requiring that every public high school include a unit on media literacy in its curriculum by the next school year.

Yonty Friesem, an associate professor in the School of Communication and Culture, was involved in the workshopping of the act, giving feedback and suggestions. Friesem doesn’t think that schools are executing the requirement effectively, as the law doesn’t require schools to collect any data showing such, they said.

“The teachers claim that they do teach, and we don’t really see that,” they said. “It’s important that it created awareness, but there’s more that needs to be done.”

Friesem said there also needs to be money for teachers to get professional development and certification requirements. “If teachers get professional development, they’ll know what they’re doing,” they said.

Olivia Byam, a senior fashion design major and registered voter in Michigan, was also required to take a civics course in high school by the state.

“I think it gave me a better understanding of democracy in the United States,” Byam said. “As far as the election or voting goes–not really.” However, she said she still felt encouraged to vote since her teacher was a very big advocate for young voters.

Byam said that nowadays, she likes to do her own research on political matters, “whether that’s through the library, like scholarly websites,” or talking to others and keeping up with the televised debates.

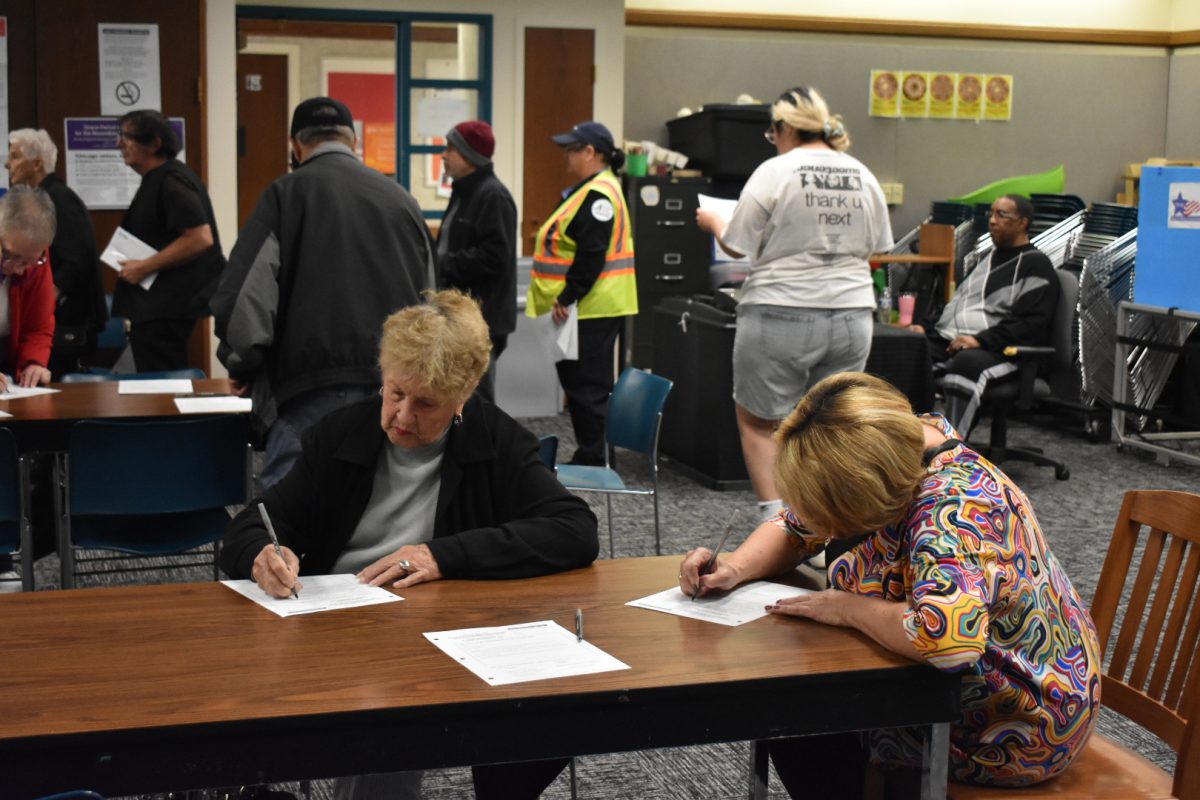

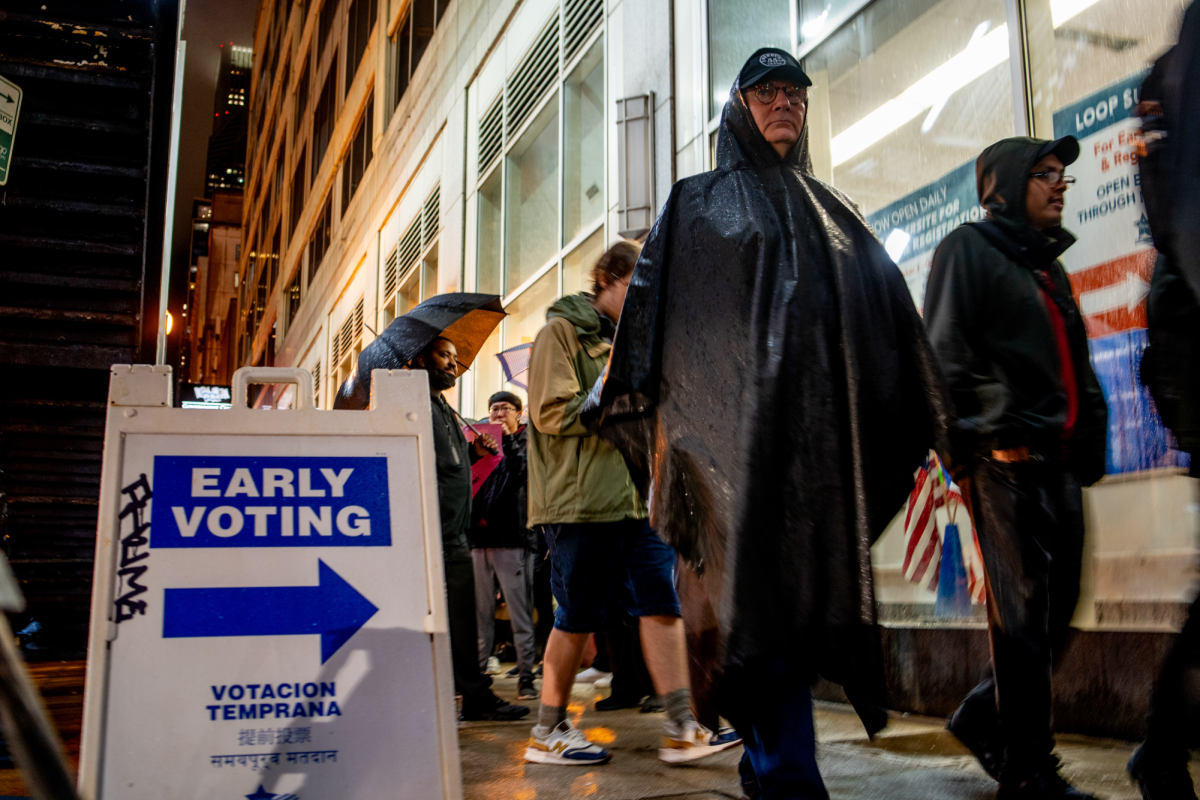

Beyond access to scholarly materials, Chicago Public Libraries also offered other educational resources and opportunities to inquisitive voters. In October, CPL hosted voter registration events across their libraries around the city in collaboration with organizations like ONE Northside and HeadCount.

“I think Chicago has plenty of resources,” Hansen said. “I think the trick is getting those resources into the hands of people who need them and delivering the content in a way that resonates with people who aren’t already seeking them out.”

Tre King, the current board director and former fellow and organizer of Chicago Votes, said that with Chicago Votes, their goal is to “help young people understand the power of their role and understand why civic engagement is important – literally to connect people like you all, young Chicagoans, with the political space in Chicago.”

In addition to civil society organizations, Hansen said that another source for credible political information is local election officials. He thinks that “local election officials have an important role to play in disseminating information about how to vote and about the election process,” he said. “These are dedicated folks often working in underfunded offices.” He referenced the Chicago Board of Elections, which is currently working on unionizing.

Hansen said he thinks these officials are doing the best they can to educate voters considering any possible “public scrutiny and sometimes threats and harassment.”

Despite all the information available to voters, Hansen said that providing accurate and credible information won’t necessarily “help restore confidence in elections.” Instead, “the bigger issue here is about how people evaluate information,” he said.

“If people are inclined or motivated to believe untruths about the electoral process, they’ll probably discount any accurate information you do give them,” he said.

Kamiyah Castellanos, a senior theater major, is a first-time voter registered in Maryland. “There is definitely a lot of misinformation being spread and fear mongering as well, which makes a lot of people nervous and confuses more than it makes it clear,” she said. “You have to know how to navigate, like media literacy, the media if you want to be less confused during the election right now.”

Segelke said one of his roommates told him he wasn’t going to vote because “it doesn’t seem like that big of a deal; it’s such a hassle.”

“That kind of opinion is what scares me, because people who I think are smart, intelligent, like these guys at law school, should be voting,” Segelke said.

Additional reporting by Emma Jolly.

Copy edited by Doreen Abril Albuerne-Rodriguez