Students of color want more diverse faculty, better connections in classroom

Columbia’s student population is getting more diverse, with the number of Hispanic, multi-ethnic and Asian students increasing in the past 10 years, according to a new data analysis from two faculty members.

In spring of 2022, less than half (48%) of undergraduate student were white, reflecting the larger demographic shift in the United States. White Americans are expected to become the minority by 2045.

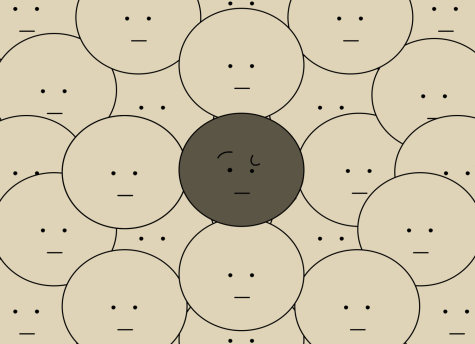

But even as the student body has become more diverse, the full-time faculty has not. The same analysis from Columbia associate professors Madhurima Chakraborty and Chris Shaw showed that 81% of full-time faculty is white.

Students of color told the Chronicle that this has impacted their experience at the school.

Almost 60% of the freshmen class of Fall 2022 identified as people of color, according to Associate Provost for Student Retention Initiatives Greg Foster-Rice. But many of them did not return. The college’s enrollment director told the Faculty Senate on March 10 that 67% of students who did not return to Columbia after their first semester as freshmen were students of color, as reported by the Chronicle.

Some students said there is a disconnect between the diversity that Columbia promises when they are admitted and what they actually see and experience once they get here.

“You’re priding yourself on something that you don’t have, only for your diversity to become lower when after the first semester half your diversity pool leaves because they can’t afford it,” said freshman graphic design major Ameriyah Coleman.

Freshman acting major Saffron Hurt was not surprised to hear that other freshmen of color were choosing not to return to Columbia after their first semester on campus. “As I started to look around, most of the students that I do see or run into are predominantly white,” she said.

Andrew Martinez, a sophomore fashion major, said that as the only Latino student in a class that was predominantly white, he felt like he “had to carry the representation of my own heritage,” and “make up for who was not in the class.”

It doesn’t help when the faculty member also is white.

Freshman fashion merchandising major Seng Xiong said in some of their classes, they were either one of a few or the only Asian student in the class.

“I don’t know if we’re just [spread across] multiple majors or it’s just we don’t have a lot of representation here,” Xiong said. “So I do sometimes feel left out.”

Coleman said he did not feel comfortable opening up to his peers in his English class because he was concerned they would not understand his experiences.

“I would love to speak on my experience within the class, but, I don’t want to talk about my experiences as a Black person only to [be met] with crickets,” he said. “What’s the point of starting a conversation that no one’s gonna finish?”

Experiences outside of the classroom have also have an impact.

Xiong said early in their first semester, their roommate at the time began to make racist jokes at a party. Though Xiong left the party beforehand, a friend told him that the roommate made “Asian jokes” and used anti-Asian slurs.

“They immediately were like, ‘Oh my God, I didn’t mean it like that, it was a total joke,’” Xiong said. But Xiong did not feel like it was a joke.

The incident “shocked” them. “I was like, wow, I really thought they never would say that, especially if they go to Columbia,” Xiong said.

Freshman cinema and television arts major Amaris Echenique said she felt she was “discriminated against” when she and another student of color were followed around the Student Center coffee shop and shouted at by a white student who worked there.

“We were just so confused and it threw us off,” Echenique said.

The college’s Antiracism Transformation Team is holding a panel discussion Wednesday, March 22, in the Student Center. The team was created in 2021 to advance the college’s diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and to “more systematically interrogate how white supremacy and other systems continue to shape institutional culture.”

The college has asked people to register for the event, which will be from 3:30 to 4:30 in the Student Center.

Rachel Horton, director of Student Persistence, an office which supports academic success, said education continues to be structured in a way that does not serve most populations well, and so many of the issues students of color face are systemic.

Horton is a fellow on the antiracism team.

“Higher education was only created for wealthy straight cis white males who did not have disabilities,” Horton said. “When someone goes to college, as a person of color, the very act of going to class is fighting against generations of racism.”

Because creative majors rely on mentorship and networking, Horton said students are dependent on faculty taking an interest in them in order to progress.

“You can be around nothing but nice people, but if you feel isolated and they don’t reflect your identity, and you haven’t had a chance to connect with them for whatever reason, then you still might sort of drift away and leave the college,” Horton said.

Echenique said she is not surprised by students’ reluctance to return to campus and she sees a lack of diversity particularly in her field.

“All my teachers are white and they can’t really relate to where I’m coming from,” Echenique said. “Some of them make comments that are not appropriate – especially either about my hair or if I bring up a concern to them that I have about their class, they really don’t understand.”

A 2018 study found that graduation rates among underrepresented students were higher when the faculty of their schools were diverse.

Horton said that students have told her that they do not feel represented in the “pretty Eurocentric” curriculum, which can make them feel “isolated.”

Though there is racial diversity among their peers in the Fashion Department, Xiong said most of their instructors have been white. Xiong said one teacher in their experience has been “a little micro aggressive” toward non-white students, and primarily teaches about white designers and fashion history.

Horton also said “bias” can inform instructors’ critiques on creative work.

“I’ve had Black students say, ‘I spent the whole critique time explaining my identity, and why I painted it this way, or why I represented it that way. And I didn’t actually get any feedback on my art,’” Horton said.

Sophomore creative writing major Yemima Kebede said that lack of diversity in faculty affects students of color in creative fields especially.

“My professors at Columbia, they’re great. They’re very understanding, and they can listen to the struggles of being a Black person — a Black creative — getting into the industry, but they won’t be able to understand or give proper advice on how to help us and how to inspire us,” Kebede said.

Freshman fashion studies major Shamya Banks said that having a diverse array of professors allows for the perspectives and information that students receive to be diverse also. “If they don’t embody the POC identity, then they need to be intentional about at least sharing resources that give insight on the perspectives that they can’t give insight on,” Banks said.

Andrea Bates, a sophomore communication major, said Columbia’s talk of having an equal and inclusive campus can be “smothering.”

“I would say they really support the creative mind and they’re not always just looking at the outside. I do think if they were to just keep emphasizing the creative mind and not emphasizing the color of the person, that might work out,” Bates said.

Hurt said the instructors in her acting classes have helped her feel supported at Columbia, and that students should look for peers with common interests.

“There’s a community for you,” she said. “You just have to have a really, really open mind, because there’s a group for everybody.”

Kebede said that she has noticed a lack of diversity across campus, but found support in her job at the Student Organizations and Leadership Office.

“Our workspace is very diverse and I love it there. It’s very inclusive, it’s very welcoming: different backgrounds, different cultures, different identities,” Kebede said.

Kebede added that she sometimes forgets that Columbia is a predominantly white institution because of how welcome she feels on campus.

“I’ve been affirmed by the people I’ve been around in that I have every right to take up space, ask questions, to aspire and make the most out of what my money is being put to work here at Columbia,” Banks said.

Since its start in 2021, Horton has worked with the Scholars Project, which provides academic support to first-year students who identify as BIPOC or first-generation students through programs and mentorship.

“Instead of treating it as student success being a student issue, we’re looking at it as an institutional challenge and how we can better serve the student,” Horton said.

Coleman said that resources at the school should be more accessible.

“If there’s resources to help us get through, I feel like I shouldn’t have to go out and look for it. I feel like it should be out in the open. [We should be] told that ‘Hey, I’m here for you, if you need somebody to talk to,’” Coleman said.

Banks said that there should be more counselors of color on campus, so that students “know that they have someone on campus outside of program leaders and professors, but someone who’s actually trained to help them and can relate to their specific or unique identities,” Banks said.

Echenique said that it would be helpful for students to be assigned a mentor. “They can partner us up with a mentor — a teacher in our field that can walk with us and coach us through, so that we don’t feel alone when we’re going through school and we feel like we have someone we can relate to,” Echenique said.

Mauricio Guerrero, sophomore music major, suggested an anonymous poll for students to discuss racial issues on campus could help with “addressing the little things that might trigger a person to actually drop out or change schools.”

llove@columbiachronicle.com

Leah Love is a senior journalism major, minoring in Black World Studies. Love has covered Chicago politics, breaking...

vrichey@columbiachronicle.com

Vivian Richey is a sophomore journalism major, who reports on the college's Faculty Senate, Columbia's COVID-19...

egonzalez@columbiachronicle.com