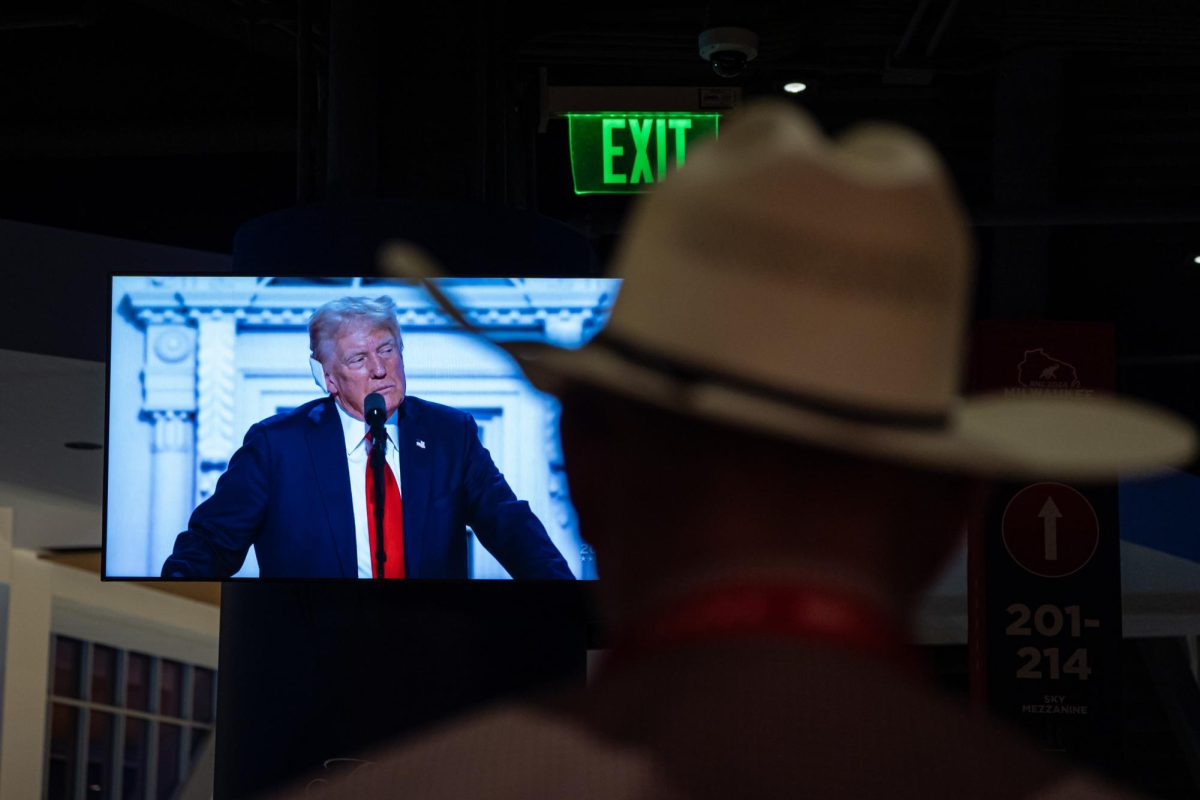

Students at Columbia are concerned about what will happen to financial aid and student debt relief when President-elect Donald Trump takes office in January.

Both Trump and his running mate, Vice President-elect J.D. Vance, have attacked higher education, even though both have Ivy League degrees. In a September debate with Vice President Kamala Harris, Trump called President Joe Biden’s student debt relief program a “total catastrophe.” Vance has called universities “the enemy,” an increasingly popular view of conservative Republicans who are set to control both houses of Congress.

The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 playbook for a second Trump term would abolish the Department of Education, privatize student loans and debt forgiveness, and undermine civil protections for LGBTQ+ students.

Although Trump cannot dissolve the federal department on his own, as the Chronicle previously reported, students nonetheless are worried about the impact on higher ed funding and resources for college students. The department manages the majority of federal student loans, worth about $1.5 trillion.

The Education department under the Biden-Harris administration provided an estimated $127 billion in student debt relief and increased university communication requirements about financial aid.

At Columbia, 48.8% of students receive federal aid, and 49% receive the Pell Grant, the largest federal grant program available to undergraduate students with the greatest need.

Because there is a possibility this funding could be impacted, students are already starting to come up with alternatives to paying their tuition if this large funding shift happens.

Junior film and television major Gabriela Ortega has thought that if she needs to, she may have to drop out and start saving up in order to ensure her success.

“I rely on financial aid from the government in order to be here, if [Trump] has plans according to how he plans it, I unfortunately will have to find another way or will have to drop out and collect money,” Ortega said. “My plan has always been to go to college, major, get my degree, and then from there start working in the field that I want, but without that type of help, I would have to drop out and actually have to be in the workforce and then collect money and try to get a career.”

Some students looking ahead to post-grad schooling have started having second thoughts considering the possible changes in available aid.

“I was looking into doing either a combined program for MFA or going into grad school, but now I’m playing it by ear based on what happens over the next four years,” said sophomore film and television major Cornell Franklin-Smith. “And since I’m a sophomore, I’ll have a lot more information like by the time I’m ready to graduate and ready to go into grad school.”

Franklin-Smith had not wavered until now on his thoughts on going to grad school, but is now planning on deciding what to do when policy is more definite. The change has also started to bring in a wave of depression among students as their possibilities may quickly become more limited.

“I was kind of sad. I was planning on going [to grad school], but now I don’t know if I can, I don’t know if I’ll financially be in a position where that’s a good decision for me, so I just have to play it by ear,” Franklin-Smith said.

James Rabon, a junior creative writing major minoring in education, is worried about the impact on teachers.

“I’m a child of a single parent from the South, so education was kind of an escape for me to get away from that environment and to pursue a career and hopefully better my future and other people’s futures as well,” Rabon said.

According to the Education Data Initiative’s 2024 Financial Aid Statistics, 56% of undergraduates, or 6.1 million students, receive federal grants each year. These grants, which have an allotted budget of $31.1 billion, close the gap of access for many marginalized communities. Without them, there will be a large gap in education, including for Rabon himself.

“I’m a first-gen student, disabled, low income, so I kind of tick all the boxes in terms of needing support and losing access to those things would essentially mean I won’t be able to get an education,” said Rabon, who graduates in 2026. “I can confidently say I do not trust what’s about to happen. I’m hoping that no big changes happen before I graduate.”

However, first-year music major Jock Savard is skeptical that Trump will actually go through with all of the plans.

Knowing Trump, “he says a lot of stuff, none of which he follows through on. But if he does follow through miraculously, then I mean, I would think I just have to pay more for school, which is kind of ridiculous,” Savard said.

Through the Department of Education, the federal government holds colleges and universities like Columbia accountable, including collecting information on graduation and employment rates. The Biden Administration put in additional protections in 2023 that further require colleges to be upfront about the value of a degree.

It’s unclear if that data would continue to be collected if the Department of Education were to be eliminated or if it were not fully funded, which is one way that its power and responsibilities could be curtailed under Trump.

Michael Romero, a first-year radio major, consistently went back to one question: Why?

“You’ve got to consider everything that surrounds education, the help that the department could be bringing, just for it to suddenly all be lost. I don’t know, it doesn’t make any sense; out of all the departments, why that one?” said Romero.

Additional reporting from Emily Ramirez and Anastasia McCarthy.

Copy edited by Trinity Balboa