Student loses $2,000 in Columbia Outlook email phishing scam

October 7, 2019

A Columbia student lost $2,000 in September after falling victim to one of several alleged dog walking job scams circulating among the school’s Outlook accounts, causing Columbia administrators to warn students to be on the lookout.

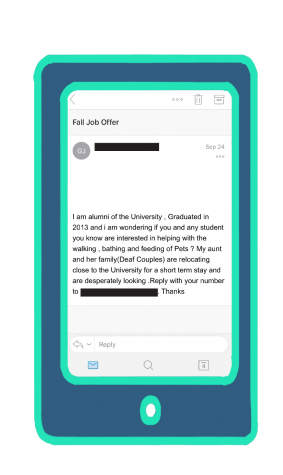

The student—whom the Chronicle will not name for privacy concerns and will be referred to by the pseudonym John Doe—said the interaction started when he received an email from a “colum.edu” account asking if anyone wanted to walk dogs for an aunt, who was identified as Janette Winston, and was moving from California to Chicago.

Looking for a lighter workload and better pay, Doe said he took the job, feeling secure that the offer had come from a fellow Columbia student because the address had a “colum.edu” extension.

Kathie Koch, chief information officer at Columbia, said this popular form of phishing attempts to coerce users into clicking on a link sent by an external source, allowing hackers to send a scam email to everyone within the institution’s email system.

“At that point, it looks like an internal email being sent,” Koch said. “It’s really being sent from the phisher, but because you clicked the button, you gave them access to our address book, and now they can send it to everyone.”

A Sept. 12 email from the Office of the Chief Financial Officer cautioned students to avoid phishing scams by looking out for emails with suspicious domains, not releasing any personal information and being wary of unrecognizable attachments.

That same day, Doe began email correspondence with the alleged scammer.

Doe was told to email Winston from his personal account because the alleged student said their aunt would not respond to Outlook emails.

The real name of the person whom the emails originated from and whether they attend Columbia is unclear.

Doe said Winston sent pictures allegedly of themself and the dogs, was very personable and crafted detailed messages, making them seem like a trustworthy figure.

“[It was] very to-the-point… She’s never asking me [about] my bank account or anything like that,” Doe said. “It always felt like she was trying to get something situated for her move. … To me, because of all the details, I just thought, ‘Oh, OK, this looks legitimate.’”

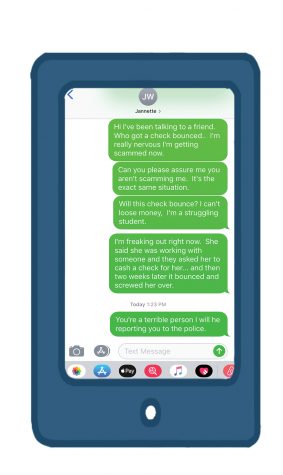

However, once they began texting, Doe said it quickly became apparent how “shady” the details of the situation actually were.

Over the course of a week, Winston asked Doe to complete a series of tasks. First, he was instructed to deposit a $2,450 check that was mailed to him into his bank account, using $2,000 to pay for appliances for Winston’s new home, keeping $350 for himself as pay for the job and using $100 to buy dog supplies.

Winston suggested Doe withdraw the $2,000 in cryptocurrency.

“[The store manager] also [accepts] bitcoin as means of payment,” Winston texted to Doe. “I can look for a bitcoin ATM not more [than] 15 minutes from you and instruct you on how to deposit it in their bitcoin account via the bitcoin ATM.”

When Doe thought the check had cleared at his bank, he opted to withdraw the money in cash, then spent it on a money order.

“When she asked me to do bitcoin, immediately I didn’t want to be involved anymore,” Doe said. “I was going to end the relationship, but I thought I had her money.”

Not wanting Winston to call the police and accuse him of theft, Doe said he then complied with more of Winston’s requests.

Doe used the cash to buy a money order, sending it to the address of an office in Indianapolis that Winston provided via an overnight delivery. The address is the location of an apartment complex.

While he was very suspicious at this point, Doe said he knew he was being scammed on Friday, Sept. 20, after talking to a friend from high school. She told Doe she was tricked in a situation nearly identical to his, where the initial check she thought had cleared later bounced.

“[It was] literally the exact same thing that happened to me,” said Doe who later learned that his check had also bounced. “I was like, f–k, I need to go to PNC [bank], right now. I already knew the cash was gone, but I didn’t want them getting into my bank account from the check itself.”

That same day, Doe went to freeze his bank account and was informed that since he had withdrawn the amount in cash and spent it on a money order, there was nothing that could be done. He then called the Chicago Police Department with help from Campus Safety and Security.

Finally, on Saturday, Sept. 21, the counterfeit check bounced, taking $2,000 out of his account. Doe is currently waiting for a CPD investigator to begin work on his case.

In its August Consumer News report, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation warned that due to federal regulation, funds may be made available in one’s bank account before the check has officially cleared. Scammers often take advantage of this by having victims deposit counterfeit checks into their accounts and then asking them to send the proceeds elsewhere before the check bounces.

While this incident caused him to lose a good portion of the money he had saved from his stressful summer job, Doe said he fortunately had enough in his account to pay back the money he had withdrawn and avoid legal action.

“At the end of the day … it’s money, it’s a setback,” Doe said. “And I have a pretty good life, I have access to education, support from my boyfriend and my mom. I have a happier life than that person who’s scamming people. But it just sucked.”

The Chronicle attempted to contact Winston but the phone line was disconnected, and they did not respond to email interview attempts.

While there is not proven correlation between the use of Microsoft Outlook and spam emails, some students have become more aware of the practice since the school’s mandatory switch to Office 365— which includes Microsoft Outlook— at the start of the Fall 2019 semester.

Nicole Denton, senior comedy writing and performance major, said she receives scam emails on her school account once or twice a week, and usually deletes them right away if they look “informal” or are not school-related.

After talking with classmates, Denton found there were other people who received variations of the same dog walking email scam she did.

“I found that weird because it seemed very informal to be sent out to a large section of the student body,” Denton said.

Senior creative writing major Alison Brackett said she was shocked and disappointed when she received an email from a professor she did not know, asking her to review an “important message from University Admin.”

“It was definitely concerning, considering [Outlook] is new and [the college is] making us use it,” Brackett said. “I would expect it to be safe, and it worries me because other people might click on the link. Because I almost did it. It was a Columbia email, so I was like, ‘I don’t have any reason not to click it.’”

Terry Cottrell—vice president for Information Technology and Planning at the University of St. Francis in Joliet and the instructor of “Advanced Cyber Security” at Northwestern University— said while there are many administrative benefits to using Microsoft, the platform is more vulnerable to spammers because it is so prevalent in the business world.

“Once an institution adopts that platform, they’ll see an increase in spam attacks, and they will need to purchase a stronger front-end anti-spam platform to try and compensate for it,” Cottrell said.

According to Koch, students and faculty should forward all scams to itphishing@colum.edu and report the instance to client services. The most important step in fighting for cyber security is helping people identify the red flags of a fraudulent email, she said.

Koch said the Information Technology Department has started raising awareness by adding banners to the tops of emails that originate from outside of Columbia and distributing fliers with warning signs such as strange URLs, poor grammar, urgent wording and requests to send money.

Within the next few months, the school will also offer interactive, internet-based modules to students and faculty through KnowBe4, a security awareness training platform designed to help people detect phishing scams.

“It’s all education,” Koch said. “We, as users, have to be really careful. It’s all in making sure people understand. If [there’s] any question at all, don’t click it.”