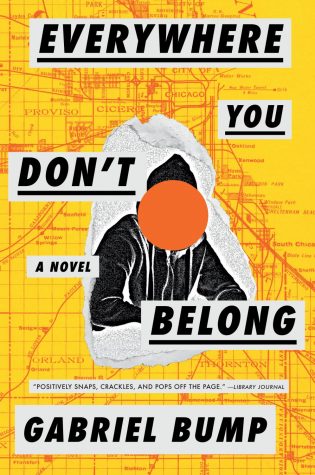

Review: ‘The microcosm of South Shore,’ a literary coming-of-age in Gabriel Bump’s ‘Everywhere You Don’t Belong’

Gabriel Bump is a Chicago native. His debut novel, “Everywhere You Don’t Belong,” takes place on Chicago’s South Side.

The city of Chicago has been documented in various ways, some positive, others more critical. The historical and political aspect of the city has been commemorated in books such as “Chicago,” by Dominic A. Pacyga, professor emeritus of history at Columbia. The social movements and morals of specific neighborhoods of the city have also been penned in novels such as Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle.”

But what exists in Chicago outside of grand sweeping narratives that encompass life itself in the city, is the personal, close-to-home and vulnerable lives of people who live in neighborhoods that are not on everyone’s radar when they think of Chicago—neighborhoods that sit south and west of the heart of the city.

Gabriel Bump—a South Shore, Chicago native—dedicated 272 pages to this very idea in his 2020 debut novel, “Everywhere You Don’t Belong.”

The plot follows the comical coming-of-age tale of Claude McKay Love, an average kid from South Shore—with the name of a Harlem Renaissance poet—who redefines who he is and where he comes from with every act of independence, every instance of vulnerability and every question of the world that surrounds him.

Bump wrote the novel over an eight-year period, starting with short stories focused on just a few of the main characters, while earning his undergraduate degree at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. He later wrote the bulk of the novel when he attended graduate school at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The narrative is one of human vulnerability and consequence that comes from taking risks—both when they do and do not pay off—intertwined with the preconceptions already surrounding people from South Side neighborhoods.

The realism evident in the writing comes from an author who is not only writing what he knows but is writing where he knows.

“The setting is pretty real. I grew up in South Shore, I grew up on Euclid Avenue—like the narrator grows up on Euclid Avenue. And there are other landmarks in South Shore and in Chicago that are taken from real life,” Bump said in an interview with the Chronicle. “It’s a made-up story; it’s fiction. But … particularly emotional elements are taken [from real life].”

The story’s arc consumes time like a vacuum, covering approximately 13 years of McKay Love’s life, shown in the novel’s dissection into two halves—the first titled “South Shore” and the second titled “Missouri.”

“We start in the [Michael] Jordan years and then move up to the eve, and then the subsequent election, of Barack Obama,” Bump said.

This coming-of-age tale does not necessarily come to a grand epiphany or life-altering decision—as many overdone narratives do—it merely tells a sincere story that needed to be told for an endearing purpose.

“At the heart of it, this book is about anti-exceptionalism. It’s about an average kid just trying to be himself, who isn’t totally concerned with being the next Michael Jordan, being Barack Obama … or [being] the next great journalist,” Bump said. “[There are] these mantles that he is incapable of reaching, just because of who he is, and I think that that’s okay that he is exceptional in non-traditional ways, or ways that society doesn’t necessarily value.”

The structure of time in this narrative does not exist to mark the progress or regression of characters alone, but of the city, too.

“Neighborhoods all over Chicago are changing really fast,” Bump said. “Gentrification is finally coming to South Shore in a real way, and the neighborhood in 10 years may not look the way it does in this book—the way South Shore didn’t look the same when I was growing up to how it did in the ‘60s.”

Considering the elements of craft at play in the novel, clipped moments in the first half push the eager reader along, such as the subsection titled “Bubbly and Nugget,” where pages at a time are spent on dialogue exchanges between characters, and even more intriguing is the dialogue tags that join them, adding another layer of depth, or often humor, to what had been said.

Lines such as, “He was old and scared and ready to make history,” or “I smelled fear and booze” tease at a larger picture not yet revealed, enticing the reader to consume the next line and the next.

However, it is the language that lingers and the complex, raw emotions woven into the text that transitions this book from a quick read to one that overhauls the way we understand the logistics of human connection. Specifically, connection that exists on the South Side of Chicago, which many Chicagoans and outsiders alike have given a negative connotation. This is realized between character exchanges, specifically when Grandma, the matriarch of this novel’s family, tries to bring justice to her neighborhood, and their neighbors “think they’re better than us,” refusing to help.

The novel needn’t say much in its short lines and stanza-like paragraphs to convey a lot about these characters who, at this time, are living a life that is simultaneously universal and a “microcosm,” as Bump would describe South Shore.

Personal to him, Bump said he hopes this story is evergreen, while still providing a snapshot of life on the South Side.

The mark of a successful story is one you can close the cover of, place on a shelf and leave open in your mind, spurring further contemplation. “Everywhere You Don’t Belong” achieves this, whether you’ve seen the lawns, homes and landmarks of South Shore or not.