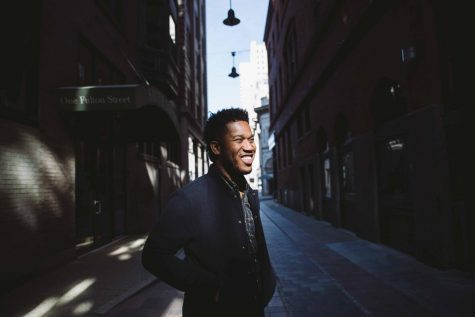

Q&A: Photographer Aundre Larrow on ‘Equity through Editing’

March 2, 2021

Although he has been involved in the practice since his early teen years, Aundre Larrow’s first formal introduction to photography was through classes he took as a journalism undergraduate at the University of Florida, where he was also the photo editor for his college newspaper.

Despite early educational experiences, Larrow said he noticed he had not learned much beyond the basics of editing in his courses. This realization led him to reflect further on the many ways photography can be inaccessible, especially for beginners.

Larrow said because of factors such as the speed at which innovation shifts, photographic practice and the legacy of racism and sexism exacerbated by gatekeeping practices, it can be difficult to learn in a way that does not perpetuate these original issues within the art form.

Larrow’s newest educational project—inspired in part by his 2018 viral Twitter thread titled “How to shoot and edit darker skin tones”—is called “Equity through Editing,” and it aims to begin addressing some of the broader issues of exclusion and discrimination within photography by making the post-production process of photo editing more accessible to everyone.

Larrow spoke with the Chronicle about the inspiration behind the educational slide series he is working on in collaboration with Adobe Lightroom on Instagram, the importance of photography and using editing to advance equity through art.

The Chronicle: What inspired you to create “Equity through Editing”?

We get really accustomed to [the things] that we see the most, which is our norm. So if you don’t learn editing techniques when you’re working at your paper or going to college, or when you’re learning photography, you’re just going to edit things like people that you admire. Maybe there’s … a kind of photo you think is awesome and you want to recreate it, but maybe when you recreated it the subject you used is not the same kind of blonde-haired, fair-skinned person. There’s just a ton of variables in photography that we don’t talk about a lot.

[For] “Equity Through Editing,” the concept was, “If I didn’t know something, and I wanted to make it for myself when I was in college or before that or even five years ago, where would I start?”

Why use the graphic slideshow format?

I’ve always found that the carousel scroll is really effective if you can get someone’s attention within the first two slides, … you can actually show something.

The point of it is to get the first line to get your interest. Then, the next slides are to actually be helpful. I think too often we’re like, “Oh, pretty thing. Let’s talk about equality. We should all be less racist.”

What was the process of working with Lightroom on this project?

It was called “Editing For Equity,” and I was like, “That doesn’t really make sense.” … “Equity Through Editing” is a nice way to put it because it’s not going to solve the problem, but it furthers the step to it. … Editing is not going to save the world, but the number of times we see bad images of Black people and Brown people that are fixable is horrible.

What are your thoughts on the impact that something like this can have on photography?

There’s a book called “Camera Lucida” by Roland Barthes. … The quote that really stuck with me … is that: “A photograph breathes a moment in time, and as a photographer, your responsibility is to capture that moment accurately. If you don’t, you’ve essentially frozen a lie, which is useless.” And so the power of photography is it not only freezes humanity, but sometimes it can be our ideal humanity or it can be inaccurate. … Perception is what we are fighting here.

You’re not taking photos to gain respectability; you’re taking photos to more accurately depict what’s going on. Sometimes that could be trauma, but other times it can just be regular, beautiful, everyday life. Some of the best Black photographers in existence just photographed everyday life, and that everyday life thing reminds people of the humanity that we’ve been constantly reminded we’re not allowed to have. So I think once you choose to get those photos, the next step is how do you take and make and edit them so they look right?

The project is important because photography is the art of observation. To be good at observing, you have to be detail-oriented, so the project is detail-oriented. The goal is to just get people to pay attention more to what they’re doing, what their presets are doing [and] what decisions they’re making with their cameras. All these things suddenly make big changes that help us perceive people better or worse.