Pushing forward: Campus leaders reflect on college’s strengths, missteps and the future

When Columbia was founded in 1890—at the time, called the Columbia School of Oratory—it was by two radical, progressive women named Mary A. Blood and Ida Morey Riley. The idea it was founded on was simple but revolutionary in higher education at the time: a place for creative-minded people to become skilled in the creative industries. More than a century later, that core value of creativity—a focus many use as a distinguishing characteristic of Columbia from other institutions—is still highlighted. But due to declining enrollment in recent years and its consequential budget shortfall, administrators felt they had to rebuild the college’s business model. That, in turn, caused some to say the college was adopting a corporate mentality.

As campus leaders contemplate goals for the next decade, administrators, faculty and students have been looking back on the past ten years to evaluate where the college fell short and where it triumphed.

By the numbers

The 2010s for Columbia were marked with challenges, similar to those faced by many higher education institutions throughout the country. According to data from Institutional Effectiveness, the decade began with enrollment down by 4% from its high of more than 12,000 students in Fall 2008; by the midpoint of the decade, enrollment was down by approximately 28% comparatively between Fall 2008 and Fall 2015. Finally, by Fall 2019, enrollment saw its first uptick in more than a decade when it increased by 122 students compared to the previous year.

Still, by the end of the decade, the size of Columbia’s student population was just more than half that of the start of the decade.

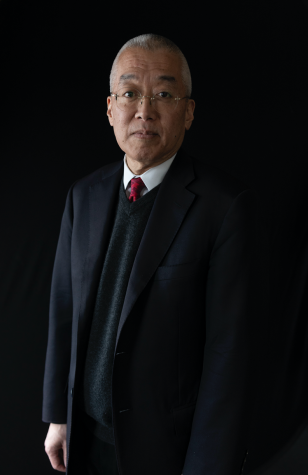

“The key to continuing the growth is to be very mindful of what young people are looking for,” said President and CEO Kwang-Wu Kim in an interview with the Chronicle.

As enrollment began to decrease, so did the college’s essential source of income: tuition.

In response to the shortfall, the college needed to adjust to a significantly smaller student population, as well as the changing landscape of higher education. The result was job cuts through the elimination of positions and faculty buyouts, streamlined resources at the student level, campus buildings sold and increases in tuition.

“[Columbia] was always focused on the right principles, and I would say about 10 years ago, unfortunately, is when I started to see … this shift … to this corporatization,” said Diana Vallera, president of Columbia’s part-time faculty union and adjunct faculty member in the Photography Department. “In the last decade, we were really guided on how much we can cut out. … It was a very limited way of thinking and one that really removed the creative visions of Columbia.”

One of Columbia’s most touted successes of the decade, though, was its ability to check off a Strategic Goal by diversifying the enrolled student population, as reported Sept. 27 by the Chronicle. From Fall 2010 to Fall 2019, the number of minority students had risen more than 10%, fortifying the college’s public commitment to its strategic Diversity, Equity and Inclusion initiatives.

Kwang-Wu Kim addresses faculty and staff about school wide changes that will be taking place, Monday, Aug. 26, 2013.

Strategic Action Plan

In the midst of many of these obstacles, which Kim inherited when he took over as president in 2013, he worked with administrators to create his vision for Columbia, called “Achieving Our Greatness: A Strategic Action Plan for Columbia College Chicago, 2015–2020.” In the Strategic Plan, six goals were outlined: student success; a 21st-century curriculum; Diversity, Equity and Inclusion; community engagement; optimizing enrollment; and aligning resources with goals.

“A phase of rapid and heady growth is behind us, and we now have an opportunity as well as an obligation to reexamine our programs, structures and practices to ascertain if, and how, they continue to advance the college’s mission and purpose,” the plan states.

Many of the action items in the plan designed to achieve these six goals included tasks such as re-evaluating whether certain resources like the Center for Black Music Research were still valuable to students; adding or modifying majors and programs; increasing enrollment rates and financial stability; and meshing DEI initiatives into students’ core curriculum, to name a few.

Kim pointed to the DEI goal as one of the most successful initiatives in the Strategic Plan, crediting it with changing the conversation surrounding diversity and issues of race on Columbia’s campus.

“We’ve begun to shift the culture in terms of how we think about how we recruit people, how we think about racism in the institution and what we’re doing about it systematically,” Kim said.

Many leaders at the college found the objectives outlined in the Strategic Plan a quantifiable success.

Sean Johnson Andrews—Faculty Senate president and associate professor in the Humanities, History and Social Sciences Department—said one of the best things Columbia accomplished in the past decade was the development of the Strategic Plan, which he said allowed the college to identify those who would be a good fit for the institution.

“What we’ve done well in the last decade is take stock of what we should be doing in the future,” Johnson Andrews said. “We could’ve been working on [that] the whole time, … so, I guess, we’re back to where we should have been, on a certain level, but maybe that detour was necessary to figure out where we stood.”

The administration has faced backlash for certain changes, such as the discontinuance of some majors and the current lack of dedicated staffing in the Center for Black Music Research.

Vallera, who sat on a committee for the Strategic Plan when it was in the works, said the plan operated as more of a show-and-tell checklist rather than a guiding set of objectives based on Columbia’s unique values that go back to its radical, progressive founding.

“It was honestly a leadership that was following instead of leading,” Vallera said.

She said throughout its history Columbia embraced “pretty radical changes as an institution, not afraid to be progressive and really ahead of its time.” Vallera would like to see the college once again embrace that mentality. “We have to change the way we’re thinking.”

Kim discounted the criticism, and said he has seen quality go up.

“I’ve never understood how people use the word ‘corporate’ as a negative because this is a $200 million business, basically, and the money—unlike corporations—doesn’t come from people buying things, it comes from tuition dollars. So, we have a moral obligation and responsibility to use that money as responsibly and effectively as possible,” he said. “The key to this plan for sustained growth is that we’re trying to get the college into a healthier financial condition so that there’s more resources to reinvest in the college and programs.”

Johnson Andrews, who echoed this pivotal overlap of serving students while being fiscally responsible, said Columbia’s idiosyncratic features, such as its budgeting or curriculum model, may give it the appearance of being corporatized, but that needs to happen because it “is an economic institution, as well.”

In large part, Johnson Andrews attributed this amplified campus culture of perceiving corporatization throughout the past decade to nationwide changes, specifically with former President Barack Obama’s changes to the Department of Education. Those changes, and ensuing requirements, in turn, caused some “growing pains.”

“We have to have that data in order to prove to the world and the U.S. Department of Education and the parents who are thinking about sending their kids to this school, we have to have that data,” he said. “But that shouldn’t be the only data we’re using to figure out if we’re successful as an educational institution.”

Vallera said the result of the changes at Columbia is a “smokescreen” for students who come here after being marketed one version of Columbia, only to enroll and find the administration more focused on profits.

“Even if [the Strategic Plan] resulted in financial stability in some capacity, it’s at what expense?” Vallera said. “We think that our students aren’t smart enough to realize what’s going on, and that’s just not true.”

Isaiah Moore, co-president of the Black Student Union, and junior TV and cultural studies double major, wants students to have the resources they’re promised when they are admitted. Moore said students who attend Columbia are looking for an inclusive, art-focused space, but feel as though the Career Center or portfolio creation is “rushed” onto them too early. In turn, they said students often decide to leave to find a different campus culture.

“Sometimes, it feels like they’re not as focused on the student experience, they’re just focused on a corporate feel,” Moore said. “There’s growing pains in some of the changes the school has been going through. It can be frustrating because we’re not hearing about it a lot of the time from a student point-of-view. … At the end of the day, the administration does work for us in our experience here, but sometimes it feels like that’s not the case.”

One solution Moore proposed is having a rotating student representative sit on all college committees to provide a fresh perspective on what students truly desire out of the college. Moore pointed to their position as a representative on the National Alumni Board as a model for how this plan could operate.

“If no one came to Columbia, Columbia wouldn’t exist,” they said.

One of the college’s most ambitious goals in the Strategic Action Plan was building a Student Center, which was finally completed in Fall 2019.

Pushing forward

Despite differing opinions on how in-tact Columbia came out on the other side of the 2010s’ many challenges, the goal for what Columbia may embody by 2030 remains in-line with Columbia’s founding value of being a place for creatives.

Going forward, campus leaders hope to expand on the goals laid out in the Strategic Plan, focusing on areas with underwhelming results, such as with community engagement, Kim said.

“By 2030,” Kim said, “I want it to be really clear that this is the school that a young creative comes to because they want to be successful in the real world; because they want to learn how to be very skilled at complex collaboration; because they believe that, as a creative, part of the definition of who they need to be is someone who is deeply engaged with the world and social issues. … And that we have the physical infrastructure to support those students.”