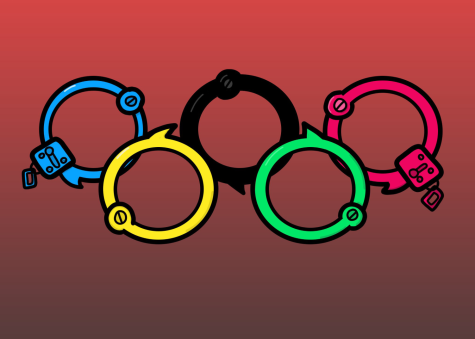

Opinion: The Olympics have always been a political platform for global issues, and this year was no different

February 21, 2022

This year’s winter Olympics in Beijing gained a lot of attention — from the world’s excitement of the Games, to the pride citizens have for their countries, to a big political issue that stood out: China’s human rights violations.

The Chinese government has targeted the Xinjiang region’s mostly Muslim ethnic minorities with internment camps and surveillance as part of a campaign of forcible assimilation, according to the Wall Street Journal. The government’s justification for these actions is to “fight terrorism and protect national security.”

Some countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, India, Lithuania and Kosovo, condemned the actions of China by joining in a diplomatic boycott and refusing to send government officials to the opening ceremony.

But others made an effort to publicly stand with China. The president of Russia, Vladamir Putin, along with China’s President, Xi Jinping, made their opinions clear. In their eyes, the Olympics and politics have no reason to go hand-in-hand.

“Together we stand against the politicization of sport and demonstrative boycotts. We support the traditional Olympic values, above all, equality and fairness,” said Putin in a televised meeting about the Olympics on Feb 3.

But the Olympics have always been a platform for social and political change, and because of the efforts people have put into having their voices heard during an event that is viewed worldwide, many countries have shifted — culturally and politically.

While a handful of nations boycotted the Olympics for various reasons at earlier Games, the first major boycott of an Olympics came in 1976 when about 30 mostly African nations sat out of the Montreal Games, protesting New Zealand’s rugby team touring apartheid South Africa, according to the New York Times. Twenty‐two African nations, along with Taiwan, Iraq and Sri Lanka, were absent from the opening ceremony of the Montreal Olympic Games.

In 1968, Mexico held the Olympic Games, but not without protest from its citizens.

Ten days before the Games started, students protested the Mexican government’s funding for the Olympics. Students wanted those funds to be used for social programs to aid the development of communities instead. They gathered in the Plaza of Three Cultures, and army officials fired their weapons. In this protest, more than 200 protesters were killed and about 1,000 were injured.

Additionally, American politics were put in the spotlight during the Mexico City Games. According to Britannica, U.S. sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos protested America’s treatment of Black citizens during the men’s 200-meter award ceremony.

Smith and Carlos stood barefoot, with their heads bowed and raised a single fist while wearing black gloves during the national anthem. The American sprinters and second-place winner Peter Norman from Australia wore human rights badges. Because of this political statement, Smith and Carlos were banned by the IOC and the U.S. Olympic Committee.

Politics have become a constant part of the Olympic Games, so saying the Olympics are no place for politics would be incorrect. The Games have always been a platform for political change and awareness, and this year was no different.

China tried to dismiss the claims of their human rights violations against Uyghurs by making Dinigeer Yilamujiang, a Uyghur cross-country skier, the face of the Beijing Olympics, having her carry the Olympic torch during the opening ceremony on Feb 4.

Multiple political issues aid the decisions of countries to stand with or against the Olympics, and there is no way to say traditional Olympic values exclude political issues. For every Olympic year, there have been politics involved in one way or another, and this year’s political involvement should not be ignored under the disguise of world peace and friendly competition.