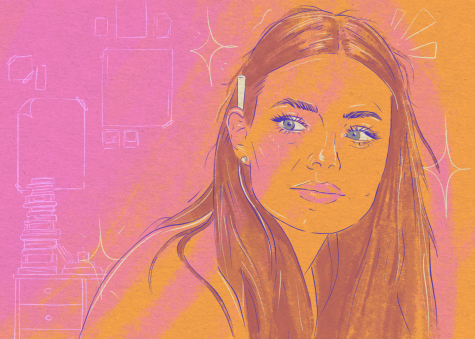

Opinion: I wanted to be a ‘manic pixie dream girl’: The effect of the male gaze in literature and film

July 22, 2021

“I stared, stunned partly by the force of the voice emanating from the petite (but God, curvy) girl and partly by the gigantic stacks of books that lined her walls,” wrote John Green in his novel “Looking for Alaska.”

When I was 15 years old, I was admitted to the hospital after severe anaphylactic shock, and I read “Looking for Alaska” for the first time there. My impressionable mind got stuck on that image of a manic pixie dream girl who says mysterious things and then disappears, leaving everyone in the room in love with her.

But no matter how hard I tried to chase that image through dyed hair, mysterious phrases and conventional looks, it always managed to slip away — until I realized many years later that I was not trying to “look for” Alaska within myself but to desperately serve the male gaze.

The male gaze is a feminist theory in which women characters are portrayed through the eyes of heterosexual men in mass media as sexual objects with a lack of individuality. The idea originates from a feminist film theory by Laura Mulvey in her book “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

Jeanne Petrolle, associate professor in the English and Creative Writing Department, said the theory of gaze evolved and scholars study not only male gaze, but female gaze, white gaze, colonial gaze, etc. because it is a “strategy of power.”

I felt that power was held over me since I was a little girl and was told not to wear clothes that were too short or too revealing. I learned to objectify my body, to hide it away from grown men who might be uncomfortable with it or even aroused.

“We live in a world of images, and power circulates through those images and who’s doing the looking and who’s being looked at and in what way; power circulates through all of that,” Petrolle said. “That’s why it’s important to analyze who’s looking, who’s being looked at and what power relationships are being transacted.”

In books, we are left to our own imagination and interpretation of the characters, while in films, we are conditioned to look at characters and their portrayal by the filmmakers.

One of the characters that inspired my rotating hair color was Ramona Flowers from “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World,” a romantic action comedy film. I viewed Ramona through the eyes of Scott, and I have to admit, I was in love with the image of her that he created, but I’m happy they never ended up together because he was in love with the idea of her and winning Ramona as a prize.

A well-known comparison between the male and female gaze is the portrayal of Harley Quinn in “Suicide Squad” and “Birds of Prey.” The director of “Birds of Prey,” Cathy Yan, said in an interview for Den of Greek that when they were creating costumes for the movie they focused on if it flattered Margot Robbie and picked outfits like they would for themselves—without any intention to impress men.

The differences between the two films are not solely based on the male and female gaze of the filmmakers but the intended audience each is trying to reach, said Susan Kerns, associate professor in the Cinema and Television Arts Department.

“‘Birds of Prey’ is a little bit different from how they were positioning ‘Suicide Squad,’ as a more male audience-oriented action film that might be more interested in Margot Robbie as a fetish object rather than as a female character with a lot of agency,” Kerns said.

Mass media was the first place where I ever experienced objectification because the majority of my family members are women. My dad passed away when I was three years old and I never admitted that it affected my mental health until recently. For the majority of my teenage years I sought male validation in my looks and behavior. I had a dominantly heterosexual male friend group for a period of my life, but I never felt included, no matter how hard I tried.

One day, I was so fed up surrounding myself with this negative energy that I cut them out without a warning, and, not surprisingly, they did not care. Since then, I started to seek validation internally; I shaved my eyebrows and finally got a mullet.

It took me a lot of therapy, self-reflection and hours of fighting against my internal misogyny to realize I do not wish to be Ramona Flowers or Alaska. I want to be myself.