OPINION: Columbia needs to make period products more accessible

October 4, 2019

While washing my hands in one of the Columbia Library bathrooms, I noticed a sign that said period products are located on the 11th floor or in the bookstore, which instantly made me angry.

If I were to get my period in the bathroom I was in and not have anything on me, I would have to go down the library elevator, walk out to the lobby and go up a different elevator to the 11th floor. Or, I would have to walk next door to the bookstore.

An August 2013 study by Free the Tampons, a group that advocates for free and accessible period products in public restrooms, found that of women ages 18-54, 86% have started their period unexpectedly in public without having period products on them. Additionally, only 48% reported getting a tampon or pad from a dispenser in the bathroom.

As of now, only Illinois, New York, California and New Hampshire have acts requiring high schools to have free menstrual products.

The Illinois General Assembly passed the Learn with Dignity Act in Aug. 2017. The act, which became effective Jan. 1, 2018, requires all Illinois schools, grades six through 12, to have free period products available in all bathrooms. Legislators concluded that period products are a healthcare necessity, and when students don’t have access, it can force them to miss several days.

Colleges are not required to provide menstrual products in all bathrooms—but they should.

However, Loyola University has a student organization, Students for Reproductive Justice, that places free period products in select men’s, women’s and gender-neutral bathrooms, according to an Oct. 3 Loyola Phoenix article.

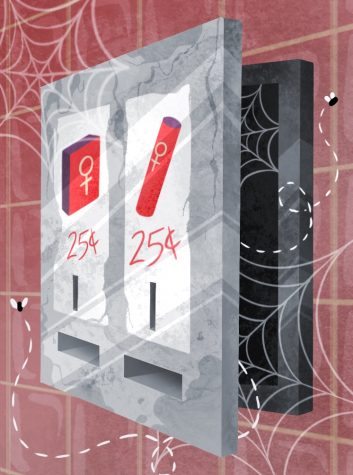

The Chronicle surveyed eight Columbia buildings to see if any of the bathrooms have period products for purchase. Most of the buildings had at least one machine in one of the bathrooms or a vending machine with period products outside the bathroom.

Lambrini Lukidis, assistant vice president of Strategic Communications and External Relations, said the machines inside bathrooms have not been functioning for 10 years. Columbia made the switch to products in vending machines because of previous issues with people vandalizing the machines and just taking the period products.

She said there is at least one vending machine in each building, with products in the vending machine usually costing $1.50. However, the Student Center, 754 S. Wabash Ave., did not have any in the vending machines. Lukidis said she would have to look into if this was something Columbia was working on getting.

Not only is it costly to pay for these products, but additionally, going to a vending machine for a pad or a tampon can be embarrassing.

There have been several times where this has happened to me, and, because of it, I decided to go home because I was frustrated. If there had been easily-accessible products, it would have saved me from missing classes, missing assignments and even missing tests.

It would be nice to be able to make it through the day with minimal interruptions because periods already have some unpleasant side-effects, such as premenstrual syndrome and menstrual cramps. Having accessible period products would be one less thing menstruating students at Columbia have to worry about while on their period.