OPINION: Ancient wonders have a lack of resonance in modern day creation

June 15, 2019

Though a crowd of onlookers in 1933 would have thought otherwise, King Kong is not the eighth wonder of the world. Perhaps the onlookers of the world at large will never find a structure or occurrence that will take that coveted spot, but we do know this much for sure—there are seven other wonders that shocked and made humans marvel at the world they live in.

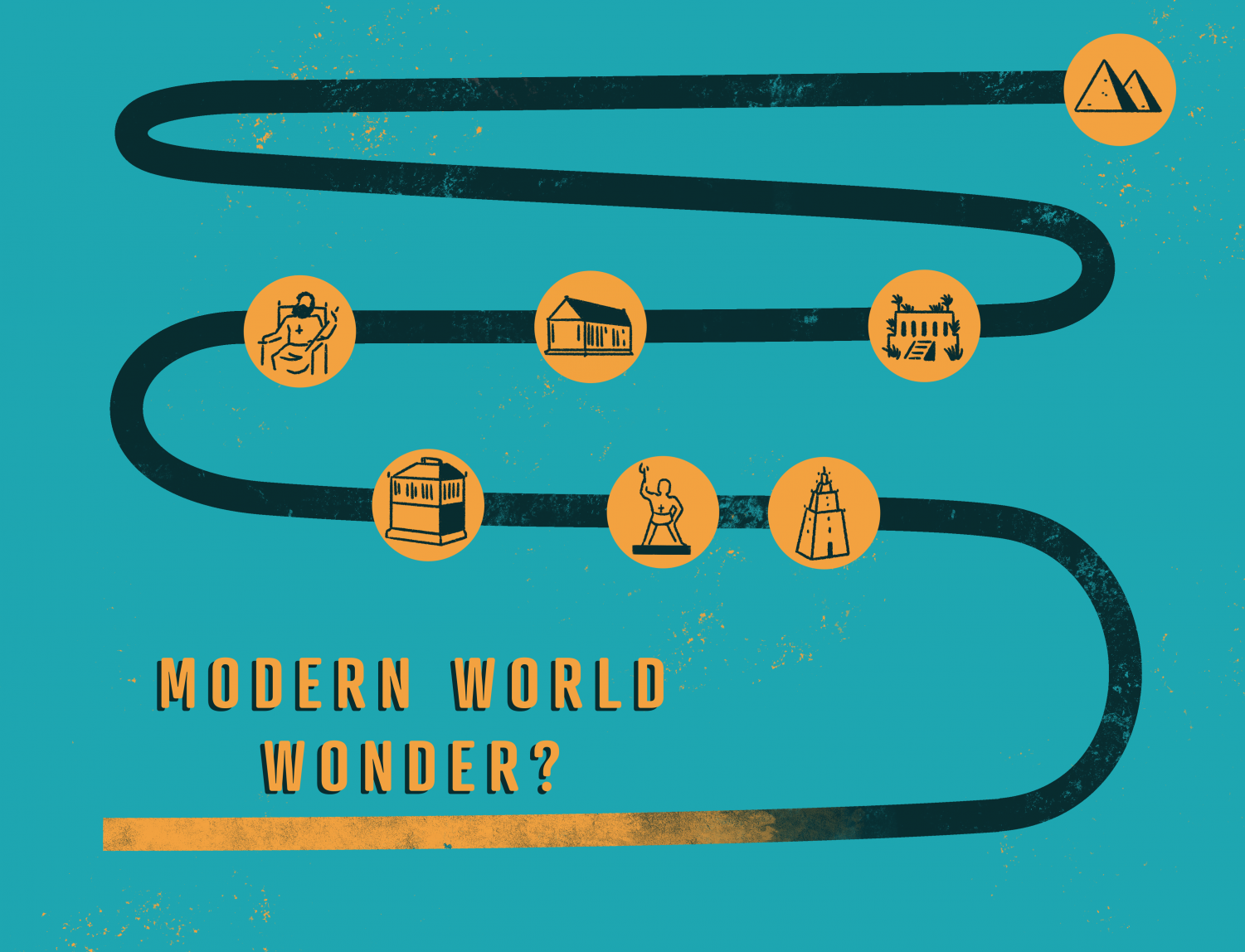

If one was to attempt to list the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, could they? Perhaps the Egyptian pyramids come to mind with ease, but what about the rest? The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus; the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus; the Colossus of Rhodes; the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, a personal favorite; the Statue of Zeus at Olympia by Phidias; and the Pharos of Alexandria, or more commonly known as the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

In our haste to be observers of the multitudes of humanity’s creations, have we yet to find a wonder of our own epoch? In 2007, an updated version of the wonders, called the Seven Wonders of the Modern World, included more recent works such as the Christ the Redeemer statue in Brazil, which was opened to the public in October 1931. Even more recently, however, our lack of desire to find something that fits in this same vein of wonder leaves the modern world at a disadvantage.

Each ancient wonder is a statement of its time and a place holder for the craftsmanship and ingenuity that existed long before the start of the modern era. To that end, the lot of us might think, “Well, what, or who, considered these to be the wonders of all wonders?”

It was Antipater of Sidon, the poet—among other men of intellectual prominence—who would be dubbed the actual compiler of the list of wonders. In a poem, comprised in 140 B.C., Antipater would write this of the wonders he had witnessed, “I have set eyes on … the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the Colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus; but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, ‘Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand.’”

What these recognizable wonders suggest is a universal community of spectators who respected these works that stretched across the world, which in turn broadened the perspective of the individual. Instead of focusing on the intricacies and impediments of any one project, it was with awe that these wonders were consumed—an experience lacking in modern times.

This is not to discredit the mode of critique often applied to modern works, however, when taking into account the technical, the metaphoric, as well as the life of the artist or creator. Yet it’s an entirely different experience to allow the sweeping feeling of awe to consume an entire international audience.

To consider the longevity of any work of art or act of brilliance, there has to be work done on the part of its audience to allow it to survive. Art, unlike any other personal conviction, can be for anyone to digest at anytime. In a world that does not allow the simplicity of existing to be enough for survival, there must be, in some sort of a second act, audience interaction. If we pause our diverted attention and set aside our bias, we could bring about that same ingenuity and promise of wonder that once existed without fear of backlash.

By allowing ourselves to commemorate a by-gone era of creation, maybe there is hope for a second wind of such wonders. To let the opportune time for conjoined expression of the masses to slip through our fingers is a betrayal of something we once collectively held sacred.

This isn’t a call for competition among finished products or the introduction of an idol, but rather the unity of attention over something much greater that speaks to a different side of humanity. There is nothing more humanizing than recognizing something for its wonder. If we turn our attention and have a similar moment of brilliance and clarity to that of Atipater of Sidon, we might all be better off as witnesses to the unceasing wonders of man.