We live in a social order in deep crisis and this threatens a whole range of institutions that refuse to define themselves completely by the logic of commercialization. Institutions of higher education may have a particular responsibility to defend themselves against the enormous attacks they are being subjected to right now.

I hope to present a “realistic defense” of the humanities in the context of President Kwang-Wu Kim’s Advisory Report, which will determine the future of this 134-year-old media and arts institution. I take the humanities to mean their most advanced traditions and what is inherently critical and self-reflexive about them.

With the advent of neoliberalism and as the logic of commodification replaces that of the public good, all things public, including universities, are viewed either as a drain on the market or as a pathology. This is bound to lead to the decline of all public institutions, which offer a sense of critical agency and social imagination.

At their very best, the humanities embody in a concentrated form certain resources and reflexes of reason, without which universities no longer meet the historic standard that distinguishes them as a kind of educational project. And without these resources and reflexes, no discipline can sustain a claim to contribute to a process of social progress and to engage in the critical and self-reflexive pursuit and production of knowledge. Without these, a discipline settles for the status of vocational and trades training no matter how high its level is. This is not to deny the value of trades training. Trades training is much like what universities have always done and some of the training is not academic at all. But that’s not the point.

The point is that even in the most specialized practice disciplines, one can’t do away with these reflexes and resources of reason. For example, whenever an artist finds herself pausing in the application of a familiar technology and an unforeseen question about its presuppositions, she has modulated from her art practice into the realm of philosophical, critical, and reflexive inquiry. Whenever two practicing physicians are negotiating what procedure to perform on a patient, based on what kind of insurance she has, they have already modulated from their medical practice into the realm of ethical and political inquiry.

These modulations are not complements; they are the signs of critical, intellectual effort at the center of received understandings in these fields. Questions about presuppositions, norms, and procedures are the natural growth points of any engaged and self-critical specialist practice.

A university or college that does not operate in this spirit is an institute of higher technical or vocational learning. So what if, in fact, universities are at the risk of being precisely the kind of organization in which that ethos of self-critical questioning is more and more of an irritant and an obstruction, something that now needs to be managed and disciplined in the interest of the pressing business at hand? In truth, the pressures are very real and administrators are, on the whole, not misleading us when they say that they can’t provide for the future without some drastic changes in programs and policies.

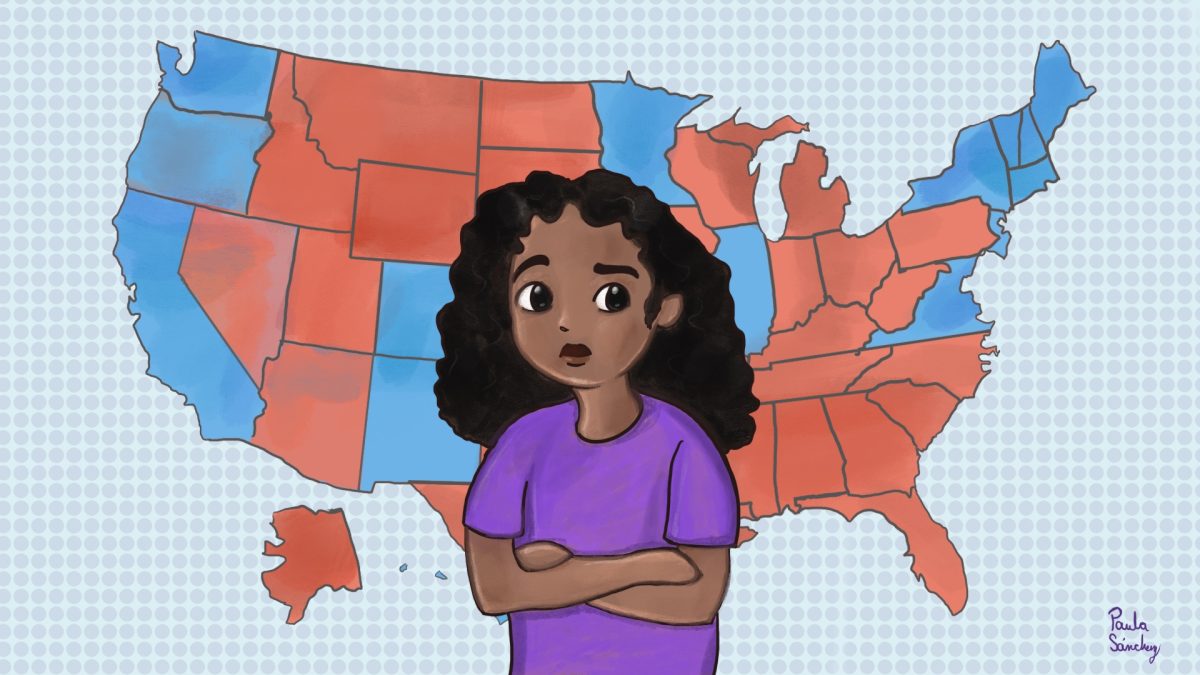

When all is said and done, universities must make their way in conditions they don’t choose. To deny this is simply to sign off from reality. The role of robust humanities is largely a question of connecting up much of what is already taught in the disciplines and the constitution of critical citizenship and democracy. What has been absent from a lot of defenses of the humanities is what the needs of a common democratic culture might be —conviction about the demands of a functioning, healthy democratic culture. What are the democratic practices by which in however limited sense the population can be said to govern itself?

A democracy is a form of governance in which alternatives are conceived, circulated, interpreted and evaluated in open debate and then decided on directly or according to various norms of representation, one in which the essential deliberative is embedded in a wider culture of investigation, criticism and advocacy, one in which the general culture supports an open play of suggestions imagining and evaluating the possibilities of a common life. It takes an enormous educational effort to sustain and foster that kind of culture, and for some of us, it takes a big effort to just begin to imagine it. And that seems to be a valuable reason for the humanities. The practices that are the everyday core of humanities learning and teaching are also the core practices of democratic culture. Therefore, as the Columbia community engages in this significant, soul-searching process, we might do well to remember that blowing up the humanities might be one of the last wires that the neo-conservative project needs to blow up American democracy itself.

Jaafar Aksikas is a professor of media studies and cultural studies in the Humanities, History & Social Sciences Department at Columbia College.

Submit an op-ed of no more than 850 words here or email editorialboard@columbiachronicle.com