Oh, the lengths Columbia students will go to shave off student expenses

September 30, 2019

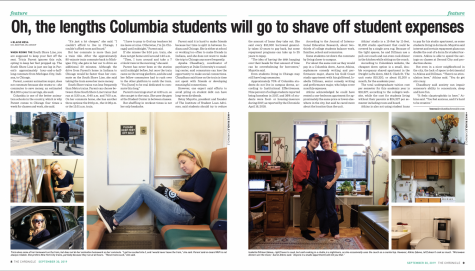

When riding the South Shore Line, you are supposed to keep your feet off the seat. Tricia Parent ignores this rule, opting to keep her feet propped up. The South Shore Line is just one leg in Parent’s approximately hour-and-a-half-long commute from Michigan City, Indiana, to Chicago.

Parent, a senior animation major, does not commute because she wants to—she commutes to save money, an estimated $14,000 a year in savings, she said.

Columbia is one of the better animation schools in the country, which is why Parent comes to Chicago four times a week for classes and work, she said.

“It’s just a lot cheaper,” she said. “I couldn’t afford to live in Chicago; I couldn’t afford room and board.”

But her commute is more than just a train ride. After the approximately 80-minute train commute back to Michigan City, she gets in her car to drive an additional 20 minutes. Although the drive from Parent’s home in Indiana to Chicago would be faster than her commute on the South Shore Line, she said taking the train saves her more money.

South Shore trains run less frequently than Metra trains. Parent can choose between three South Shore Line trains that run at 5:30 a.m., 6:40 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. On her commute home, she has another three options: the 9:16 p.m., the 11:06 p.m. or the 12:51 a.m. train.

“I have to pray to God my teachers let me leave at nine. Otherwise, I’m [in Chicago] until midnight,” Parent said.

If she misses the 9:16 p.m. train, she does not get home until around 1:40 a.m.

“Then, I turn around and take a 7 o’clock train in the morning,” she said.

Parent has never been at the station until midnight before, but once the train came on the wrong platform, and she and her fellow commuters had to rush over to the other platform to catch the train. “You [have] to be real dedicated to commute this long.”

Parent’s mornings start at 4:30 a.m. so she can get to the train. She uses the gym at the Student Center in between classes.

But shuffling in workout times is not her only headache.

Parent said it is hard to make friends because her time is split in between Indiana and Chicago. She is either at school or working too often to make friends in Indiana, and she does not want to make the trip to Chicago any more frequently.

Ayesha Chaudhary, coordinator of psychiatry at Duke University’s counseling center, said commuters can lose the opportunity to make social connections. Chaudhary said time on the train is time not spent with friends or developing meaningful connections.

However, one expert said efforts to avoid piling on student debt can have long-term dividends.

Betsy Mayotte, president and founder of The Institute of Student Loan Advisors, said students should try to reduce the amount of loans they take out. She said every $10,000 borrowed generally takes 10 years to pay back, but some repayment programs can take up to 25 years to repay.

“The idea of having the debt hanging over their heads for that amount of time can be overwhelming for borrowers,” Mayotte said.

Even students living in Chicago may still have long commutes.

Approximately 70% of Columbia students do not live in campus dorms, according to Institutional Effectiveness. Nine percent of college students reported being homeless in 2017, and 36% of students were food- or housing-insecure during 2017, as reported by the Chronicle April 16, 2018.

According to the Journal of International Education Research, about two-thirds of college students balance work, families, school and commutes.

Some students cut down the commute by living closer to campus.

For about the same rent as they would pay in a Columbia dorm, Aaron Atkins, sophomore comedy writing and performance major, shares his Gold Coast studio apartment with his girlfriend, Isabella Dillman, senior comedy writing and performance major, who helps cover monthly expenses.

Atkins acknowledged he could have rented a one-bedroom apartment for approximately the same price or lower elsewhere in the city, but said he cared more about the location than the unit.

Atkins’ studio is a 15-feet by 11-feet, $1,200 studio apartment that could be covered by a single area rug. Because of the tight spaces, he and Dillman use a pull-out couch and can even cook dinner in the kitchen while sitting on the couch.

According to Columbia’s website, the cheapest dorm option is a small, double occupancy shared apartment in the Dwight Lofts dorm, 642 S. Clark St. The unit costs $10,320, or about $1,200 a month, for the academic year.

The total undergraduate tuition cost per semester for this academic year is $16,327, according to the college’s website, while the cost for students living without their parents is $24,327 per semester including room and board.

Atkins is also not using student loans to pay for his studio apartment, as some students living in dorms do. Mayotte said interest and certain repayment plans can double the cost of a dorm for student borrowers. Atkins is able to spend the savings on classes at Second City and production shows.

But even in a nicer neighborhood in the city, the lack of space is detrimental to Atkins and Dillman. “There’s no stimulation here,” Atkins said. “You do get

stir crazy.

Chaudhary said anxiety can impair someone’s ability to concentrate, sleep and have fun.

“It feels claustrophobic in here,” Atkins said. “You feel anxious, and it’s hard to be creative.”