LGBTQ history finds a home on the page— sex toys, birdcages and all

April 19, 2019

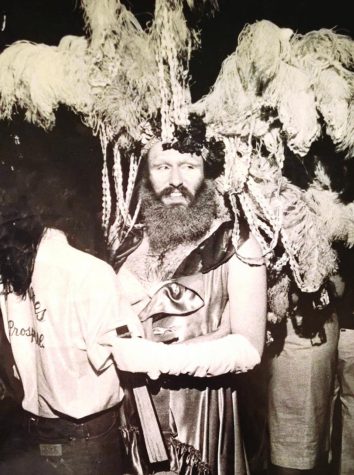

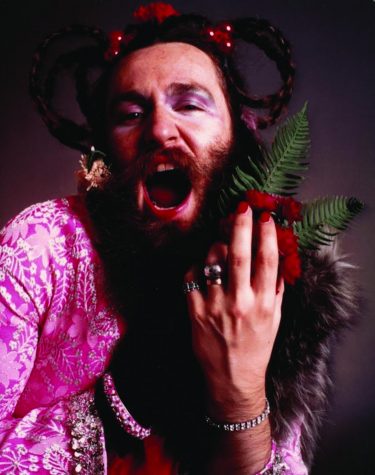

In 1974, people who visited Dugan’s Bistro in River North between midnight and 2 a.m. may have been lucky enough to stumble upon the Bearded Lady, stripping down to her one-piece bathing suit with a birdcage in her hair while The Isley Brothers’ “Who’s That Lady” blasted in the background.

Dugan’s Bistro—once at 420 N. Dearborn St.—has been gone almost four decades, but grassroots LGBTQ historian and writer Owen Keehnen is doing all he can to hold the whispers of its legacy and that of the Bearded Lady together.

Keehnen said he has been recording LGBTQ history since the 1980s, when he started interviewing activists and writers in the community simply to chronicle their stories.

When he first started writing nonfiction books in 2010, he realized so much LGBTQ history is out there but not consolidated. He said making sure these local, personal accounts are written down is important, otherwise they can be lost in the general cultural narrative.

“[The Bearded Lady’s act] … was this incredible celebration of fun, and it … embodied the carefree attitude [of the community], especially during the pre-AIDS era,” he said. “I really wanted that captured because … gay history can get really simplified in the modern era.”

Keehnen’s recently-released book, “Dugan’s Bistro and the Legend of the Bearded Lady,” was conceived after he spoke to someone about the gay nightlife scene of the 1970s and they said they could not imagine how the Bearded Lady spent her time offstage.

“Immediately, that was like catnip for me,” he said. “I became obsessed with finding out what the Bearded Lady [did] in their day-to-day life.”

What was originally a book about various entertainers of the era, including the Bearded Lady, evolved into a story of her own and of Dugan’s Bistro.

Dugan’s Bistro was sometimes called “the Studio 54 of the Midwest,” a reference to a nightclub in New York that was an iconic part of the gay nightlife in the ‘70s. However, Dugan’s Bistro actually opened in 1973— “four years before Studio 54,” Keehnen said. “In other words, it opened half the disco era earlier, and a lot of the disco norms … were pioneered by The Bistro.”

The Bearded Lady’s routine would begin with her back to the audience—what Keehnen said she called “giving back to the community”—and would then turn the performance into a kind of burlesque routine, stripping away layers upon layers of house dresses and ponchos until she got down to what was typically her one-piece bathing suit.

Her only rule, Keehnen said, was that nothing could go over her head, so as not to disturb the objects she had strewn in her hair and her beard, which could include anything from sex toys to lawn ornaments. In Keehnen’s favorite example, a telephone handset was suspended by wires, and out of the receiver was a speech bubble that read, “Hello.”

Junior cinema arts and science major Halonah Abraham Paiss thinks that in general, queer history is ignored in history classes, and says it’s important for those stories to be shared so young queer people feel represented.

According to junior fiction major Jerakah Greene, it is also important to share LGBTQ history with young people because it gives them context for what came before them.

“We have tunnel vision, all of us do, and it’s really important to know where we came from and the reason we have marriage equality, the reason [people ask about pronouns],” Greene said. “That didn’t just happen. People made it happen. It can be really irresponsible not to take it upon yourself to learn that history and take account of the privileges we have as queer people in 2019.”

However, Keehnen said it is crucial to not just focus on the heavier parts of the past. With the dark cloud of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s hanging over the LGBTQ community, Keehnen said stories from the 1970s often get glossed over because they seem “frivolous” in comparison.

“It’s a great way to also celebrate a lot of those people who were lost in the AIDS epidemic,” he said. “To portray them as these people having an incredible time and being more than a grim statistic. These were human beings, and a lot of them were having the time of their lives.”