Intergalactic lesbians, lavender labryses and everything in between

October 11, 2019

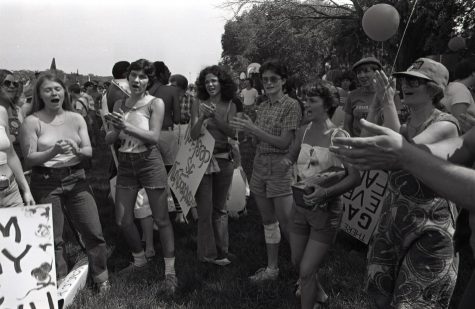

Lesbians in 1977 Gay Pride Parade. Judy Brabec on the left, In the middle: Kathleen Thompson and Christine Masterson.

In the 1970s and 1980s, lesbians and feminists in Chicago did not have to look far to find spaces to call their own.

In Wrigleyville, they could hole up in Susan B’s, a restaurant that only served two kinds of soups, which rotated daily. On the Near South Side, they could share a beer in MS, an intersectional and intentionally unsegregated bar. In Lincoln Park, they could wander the shelves of the activist bookstore Pride and Prejudice.

In its exhibit, “Lavender Women and Killer Dykes,” opening with a reception Oct. 12 at 7 p.m., Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, 6500 N. Clark St., will bring spaces like these, as well as the people and activist movements behind them, back to life, at least for the duration of the exhibit.

The title of the exhibit references two Chicago publications from the 1970s and 1980s, which served as source material for the exhibit—Lavender Woman, an explicitly lesbian feminist newspaper that included everything from surveys of lesbian bars in Chicago to articles about single mothers—and The Killer Dyke, a radical and satirical newspaper that was run by the Flippies, or the “feminist and lesbian intergalactic party.”

The exhibit was co-curated by Gerber/Hart volunteers Jen Dentel, Erik Rebain, Isabel Singer and David Sievers. It will examine lesbian and feminist community spaces from the time in all forms, such as bars, restaurants, health centers, music venues, publishing presses and bookstores.

While the original intention was to specifically highlight lesbian feminist spaces and groups, that scope expanded as the curators realized the tension that exists over the term “lesbian feminism.”

“It’s an interesting idea,” Rebain said, “because there was the whole concept at the time of political lesbianism. So it was, you don’t have to be sexually attracted to women, you just have to give your energy to women to be a lesbian. So people who were sexually interested in women and people who were not kind of clashed on that. … It was contentious. So we’re looking at both lesbians who are sexually interested [in women], and then just feminists, because that covers a much broader spectrum.”

A lot of underlying tension arose in feminist and lesbian activist movements at the time, particularly around the idea of separatism. Mary Ann Johnson—president of the Chicago Women’s History Center, which co-sponsored the exhibit with Gerber/Hart—said separatists were women who advocated for the refusal to “deal with” men in any way, whether this meant rejecting them from physical spaces dedicated to women or not welcoming men into their lives at all.

A regional example of a separatist space was the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, an annual music festival that was held in western Michigan.

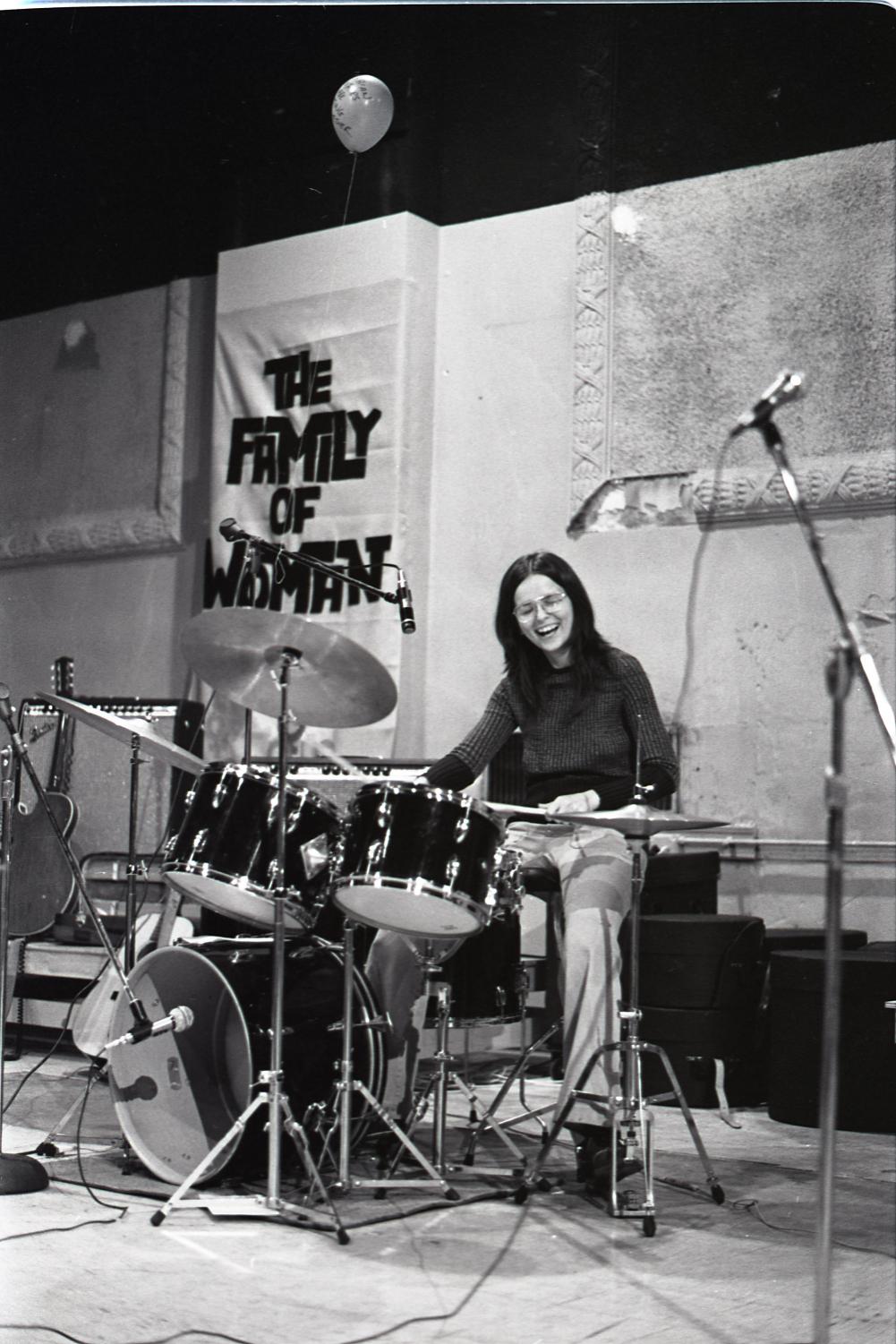

Ella Szekely, drummer in the Family of Woman lesbian feminist band.

If someone hadn’t gone to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, Rebain said, “you’d kinda lie about it and say that you went so you’re [considered] a real lesbian.”

Women’s publishing houses and female vendors selling feminist and lesbian items, such as the labrys—a double-bladed battle axe symbol of lesbian strength and independence—populated the festival camping grounds. The festival ran from 1976 to 2015, Rebain said, and had a strict no-men policy, which included children. Women who brought their sons had to keep them in a sectioned-off area, away from the rest of the festival. It was eventually shut down because of the national backlash it received for its trans-exclusive policies, as it only allowed “women-born-women” to attend.

Despite these transphobic and separatist divides in the lesbian and feminist movements, there were intersectional and inclusive spaces and organizations throughout Chicago, one being the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, a socialist feminist organization.

CWLU stood apart from other feminist organizations because it advocated for lesbian causes, while many mainstream feminist groups thought that mentioning lesbian rights would be “distracting,” Sievers said.

The Lesbian Feminist Center, originally named the Chicago Women’s Center, also ensured it brought groups together, Johnson said. It included a bookstore that sold lesbian and feminist books, the New Alexandria Library for Women and lesbian-positive counseling services provided by lesbian therapists.

Dentel hopes the exhibit will not only educate the public about history that often flies under the radar, but that it will also shine a spotlight on grassroots activism and community work that has long gone unrecognized.

“When there’s this telling of queer history, you get Stonewall, AIDS, gay marriage, that’s kind of all you get. And it’s like, well, that’s not all [there is],” Dentel said. “Chicago gets left out of a lot of the conversations about [LGBTQ+] history. … So being able to celebrate Chicago and actually look at those physical spaces that existed in Chicago, and the women that were in Chicago, is important.”