‘I’m no different than anyone else’: LGBTQ Christians share their journeys to finding acceptance

May 21, 2021

Editor’s note: This article is one in a series of stories from the Communication Department’s award-winning Echo magazine, featured this summer on the Chronicle site.

_____________________________________

Standing among a bustling crowd of thousands awash in glow sticks and phone screens at a Hot Hearts religious music festival, Tabitha Samuel looked up at her idol, Christian singer-songwriter Natalie Grant, and her heart sank. As a queer woman, Samuel thought she would never know what it felt like to passionately perform worship music.

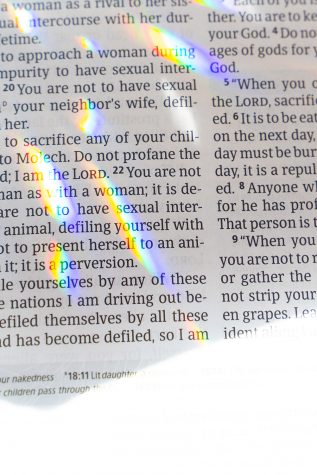

Like generations of LGBTQ Christians before her, Samuel struggled to reconcile her faith with what she had been told about people like her:

You’re going to hell. I love you but I don’t accept your sinful lifestyle. God wants you to repent and change your ways. You can’t be Christian and gay. God created man and woman. Man shall not lie with man.

For members of the LGBTQ community, especially those who grew up Christian, these phrases are deeply familiar. The hurtful words from people in church pews and pulpits put LGBTQ Christians at odds with themselves and hinder their ability to figure out their identities, meaning most have a long journey to recovery and self-acceptance.

Samuel says she has been in church her whole life while living in Texas, which is part of the Bible Belt.

Around age 14, Samuel realized she was queer, and in spite of her religious upbringing and many sermons condemning equal marriage as a sin, she wasn’t ashamed to talk about it.

In high school, Samuel planned to audition for a role in the church worship service, where she would be able to play guitar and sing, until her youth group leader told her there was “no way” she would be able to do that because of her sexuality.

Discouraged and hoping to gain some clarity, Samuel asked the youth group leader for answers regarding her faith.

“Can I be gay and Christian, does God love me the same, and will I go to heaven or will I go to hell? Those [were] my three big questions,” Samuel says.

Quickly, the youth group leader answered that Samuel could not be “actively gay” and Christian, that God hates sin and, essentially, that Samuel could not go to heaven.

“I was struggling for about two or three months after that conversation,” Samuel says. “I was looking up research and all these things. One day I was like, ‘You know what, I don’t even care anymore. I am who I am. God loves me the same, he’s made me. I’m no different than anyone else.’”

Matt Nightingale, a gay spiritual director, teacher and pastor in Santa Rosa, California, grew up in a fundamentalist evangelical community in Northern Indiana. While Nightingale knew he was gay early on in life, he loved his church and Christianity was important to him and his family.

“I had no role models of healthy gay people, let alone Christian gay people,” Nightingale says. “I knew even at the age of 10, I just needed to shove that down and hide it.”

After becoming a full-time music minister in 2000, Nightingale began coming out to people, including his wife, because he was convinced it was sinful to be gay and he wanted to be healed. He tried conversion therapy, support groups and a 12-step recovery program for sex addiction, to no avail.

Eventually, he began to accept and embrace the label of gay and found that God blesses same-sex relationships and queer identities. Then, in 2016, he left his mixed-orientation marriage and resigned from his local church to start a new life as an openly gay man.

After training to be a spiritual director in a two-year program, he started the group Spiritual Conversations for LGBTQ people of any faith to connect with God and spirituality. During the coronavirus pandemic, around 30 group members have attended Zoom sessions every other week.

He says other queer Christians have helped him affirm his own sexuality and faith through exhibiting the “fruit of the Spirit.”

“I just couldn’t deny that I saw healthy, faithful spirituality in these people who I have been told my whole life, couldn’t be authentically Christian,” Nightingale says.

Donté Jones, a pansexual United Church of Christ pastor, says he has been preaching since he was “like six years old.”

Growing up in the conservative environment of a Black Baptist church, Jones says once he discovered in his youth that he liked the same gender, he wrestled internally with the discontentment and shame he felt surrounding his identity.

“My whole life is a journey of self-discovery, embracing and celebrating authenticity,” Jones says. “For me, the whole story of Christianity from Genesis to the story of Jesus is the story of life being that conduit in which [people] discover their relationship to this divine thing and their relationship with themselves and each other.”

At his current church in Central Pennsylvania, he says the congregation loves authenticity and does not want anything other than the truth. So, the topics of his sermons have no limits and often include LGBTQ-affirming messages.

“Where I found Jesus, when I was going through my coming out phases, was in the gay clubs of New York City,” Jones says. “No matter who you [were], nobody questioned you, you were always welcomed, you were loved. To me, they were more like Jesus than the people that were preaching hate.”

Aaron Brown, a counselor at The Christian Closet, an online resource for LGBTQ people looking for therapy, spiritual direction and coaching, says it has been gratifying to help other LGBTQ Christians continue their spiritual journey without hating the Bible or completely ditching what they have learned.

“What I see with a lot of people is their identity feels very split,” Brown says. “Not even so much because of religion, but because of how once they step outside of that, they lose a sense of belonging.”

While involved in a season five episode of the Netflix show Queer Eye, Noah Hepler, a pastor at Church of the Atonement in Philadelphia, says the Fab Five cast helped him process leftover baggage he was carrying after coming out later in life. This gave him the drive to work on his theological dissertation and better lead his small congregation.

Although there is still more work to be done, Hepler says he has taken significant steps toward accepting himself.

“I don’t really know where I am,” Hepler says. “And I’ve learned to be more okay with that.”

He says during filming for the show he realized Christian churches need to engage in genuine reconciliation with those it has oppressed on the basis of sexuality and gender as well as race.

“We’ve done incredible harm to people, and they may never come back to church,” Hepler says. “And that’s not their fault. It’s ours.”

Hepler says it is important that affirming Christians walk with and empower people who have been harmed by those using the faith abusively.

“We might not have been the individuals who actually harmed you, but we know we’re part of the community that did,” Hepler says. “And we’re going to honor and respect your story and work hard to change things so that won’t happen to anyone else.”

For Christians not part of the LGBTQ community, it can be especially difficult to depart from what they have been taught and accept those identifying with various sexualities and gender identities.

Susan Cottrell, the founder and president of FreedHearts, an LGBTQ Christian advocacy organization, founded the network with her husband after their oldest child came out and they realized the church did not know how to support Christian families with LGBTQ family members.

At first, Cottrell was worried and confused, wondering if her child would find love and acceptance. To try to come to a consensus, Cottrell got out research materials on LGBTQ people in the Bible and spread them on the kitchen counter, reading and sorting, when suddenly she just pushed everything aside, and said, “There’s no love in this.”

“If there’s no love in it, it’s wrong,” Cottrell says. “You’re on the wrong track. Jesus said love God and love others. Anything that doesn’t line up you need to scrap that and start over again.”

Following this revelation, Cottrell began reading and listening to LGBTQ people’s stories and eventually went on to a progressive seminary school. To her, the end game is being at peace with God, rather than fitting into theology or construct.

“Since I began this journey, I have become a much more loving, kind, beautiful, accepting human being,” Cottrell says. “Much more Christ-like than I ever was when I was in the church.”

The Rev. Richard Lanford of St. Peter’s United Church of Christ in Skokie, says while he came to the church in 1992, the congregation did not vote in favor of becoming LGBTQ affirming until Pride Sunday in June 2018. Lanford first went through his own theological process and gauged church members’ interest in being part of an open and affirming community.

As an open and affirming church, the congregation holds same-sex marriages, observes Transgender Day of Remembrance during worship by saying the names of transgender people who have been killed in Chicago and attends various pride month events.

At Samuel’s new church, there are plenty of messages about accepting everyone and opening the doors so that everyone can follow God’s word and feel his love. She is in a fulfilling relationship and is also able to sing in front of the congregation.

“I feel closer to God when I’m listening to Christian music and playing Christian music,” Samuel says. “It’s just me and him when [I’m] singing or when I’m worshipping.”

Samuel says from the very beginning Christians are taught “Jesus loves me this I know,” in nursery rhymes and should remember this going forward.

“You are seen, you are loved,” Samuel says. “You are heard and you are valid. You don’t have to be the ‘perfect Christian,’ to be loved and be accepted by God. There’s no such thing.”

_____________________________________

The 2021 issue of Echo will be available this summer on newsstands across campus, and PDFs of all issues are available online.