‘Stills’ move Art Institute

Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago

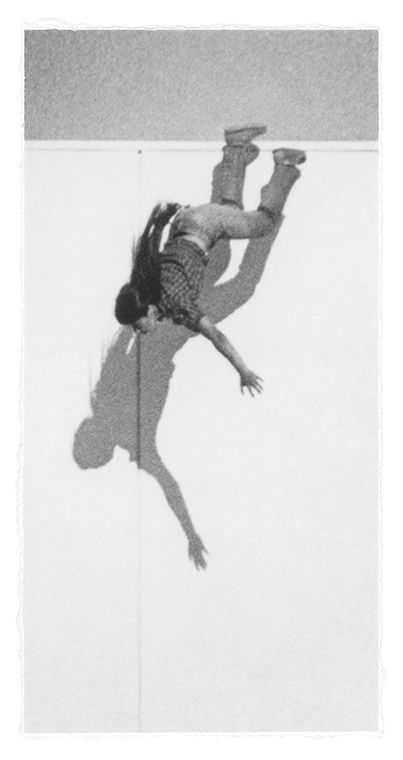

Sarah Charlesworth. Patricia Cawlings, Los Angeles, 1980, printed 2012, No. 10 of 14 from the series Stills. The Art Institute of Chicago, Krueck Foundation and Photography Gala Funds,2013.129. © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth. Courtesy the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth and Maccarone.

December 8, 2014

Conceptual artist and photographer Sarah Charlesworth’s series “Stills” is being shown in its entirety for the first time at The Art Institute of Chicago, 111 S. Michigan Ave., and is evoking a variety of reactions from visitors.

Charlesworth’s “Stills” attracted much attention when the original series, consisting of seven images, were first presented in February 1980. That was the last time any of the pieces, as well as six others that was previously omitted and one created years later, would be shown to the public. Charlesworth died suddenly in 2013 from an aneurysm and was discussing a “Stills” exhibit with Matthew Witkovsky, curator of the Department of Photography at The Art Institute of Chicago, at the time. The exhibit features all 14 of the original pieces depicting people who jumped or had fallen off of buildings, shown as a whole collection for the first time.

Witkovsky said in an email that the conceptual art movement in America that Charlesworth was involved in influenced her own work and continues to influence artists and photographers today.

“Conceptual art is perhaps the most significant movement in art of the past 50 years in the sense that it has inspired and continues to inspire generations of artists around the world,” Witkovsky said. “It arose in the ‘60s as a set of tendencies questioning the institutions of art, how art is placed before an audience and valued as important.”

Matthew C. Lange, the studio manager for the Sarah Charlesworth estate, said Charlesworth took the photos of the newspaper clippings of the falling bodies when conceptual art in America was blossoming. He also said Charlesworth took a different approach than her peers.

“Her work was a little more photocentric than a lot of the conceptual art that had been shown in the 1970s,” Lange said. “One of the big things with ‘Stills’ was she started taking little tiny fragments of newspapers and tearing out these little tiny pieces and blowing them up on a grand scale, making them 6 feet tall, something that was kind of dehumanized by being reduced to a small printed picture. She was attempting to re-humanize in a way, to put it back on the human scale.”

Lange said Charlesworth pulled about 70 photos depicting images of people who had jumped or fallen off buildings from newspapers. This method of appropriating images was common in conceptual art at the time, but Charlesworth always added an aspect of personal tangibility, such as leaving the torn edges on the photos, to make the pieces her own, Lange said.

“She was working with found imagery—she was kind of reusing, recycling, representing images,” Lange said. “But she was also doing something by enlarging them by sort of changing the scale, trying to insert a little bit of her own subjective presence in there. I think that the torn edges are really important in that they show you that this isn’t an image that I’m reproducing, that this is something I’ve had in my hand, that I’ve touched and interacted with.”

Witkovsky said the method Charlesworth used when creating the images—cropping and photographing the newspaper clippings—allows for the viewer to question what he or she is looking at despite the reality of the photographs.

“Charlesworth has cropped these images, removing any ground or land element, suspending the subjects in midair,” Witkovsky said. “We know that these people have jumped, but she does allow us some disbelief about what we are actually looking at, disbelief or uncertainty. We are shown a storyline midstream, deprived of either a starting point or a conclusion.”

Lange said the sense of disbelief viewers experience when looking at the images of the falling bodies was a conscious effort by Charlesworth.

“That’s a really important part of how you interact with them,” Lange said. “You don’t know, you’re never quite certain, you should be sort of held there stuck on that idea…. It was actually really important to Sarah. She knew the story behind each one and spent a lot of time thinking about what each story meant in the series.”

Lange read from an unpublished statement written by Charlesworth explaining her work.

“The large blowups that comprise the series each depict a person in midair, frozen by the camera in a moment of suspense between certain life and possible death. The startling commentary on the ever-present threat of violence within the visual landscape of media and culture as well as a pointed philosophical reflection on the limitation of the narrative capacity of photography, these individuals perpetually frozen, divorced in the moment of the photographs from the intentions preceding the jump to end or preserve their lives. Likewise, the outcome, the completion of the narrative in life or death lies beyond the scope of the frame, drawn primarily from wire service photographs depicting fires or suicide attempts, the pieces, the suspended narratives are titled only by name, sex or geographical location of the individual depicted without reference to other textual information,” Charlesworth wrote.

Although the images are provocative and similar photographs have drawn criticism when published in newspapers, Lange said there has never been any backlash against Charlesworth using images of real people falling or jumping, sometimes to their deaths.

“It’s kind of surprising, actually,” Lange said. “There hasn’t been anybody who has ever really been angered by them, upset by them … nobody’s ever gone after her for showing somebody in a certain way or wrongfully depicting any of the people in the pictures.”

“Stills” runs through Jan. 4.