50 years later: Columbia in 1968

September 4, 2018

Dominated by political turmoil and public unrest, 1968 is a year imprinted on U.S. history.

The United States continued its involvement in the Vietnam War and launched the Apollo 7 and 8 flight missions. The civil rights movement reached new heights after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April. Much of the U.S. was devastated, and flames engulfed Chicago’s West Side as protestors took to the streets.

Just a few CTA stops away from the center of the protest marches sat Columbia’s main campus building, 540 N. Lakeshore Drive, where many students and faculty studied and participated in the movements.

In January 1968, Columbia had 70 faculty members and approximately 500 students. The small but growing college worked toward its goal—which some would say has been achieved—of creating a center for contemporary film education by establishing a department of motion pictures, among other expansions.

Also in 1968, Columbia adopted its mission statement, which is still used today, to encourage students to author the culture of their time. Then-President Mike Alexandroff challenged trustees and faculty during a January 1968 speech to produce these unique students, saying: “We cannot turn back from the transcending moral imperatives of our times. We’ll be damned if we do.”

Heidi Marshall, head of Archives and Collections at the Library, said Columbia’s continuous social engagement is the result of the philosophy of the college during the ‘60s.

“Columbia has involved itself historically in a lot of large social movements. In the ‘60s, Vietnam and Kent State reactions, and up through the ‘80s, when you had the provost and president picketing outside the South African consulate to protest the apartheid government in South Africa,” Marshall said. “There has always been this engagement with the community.”

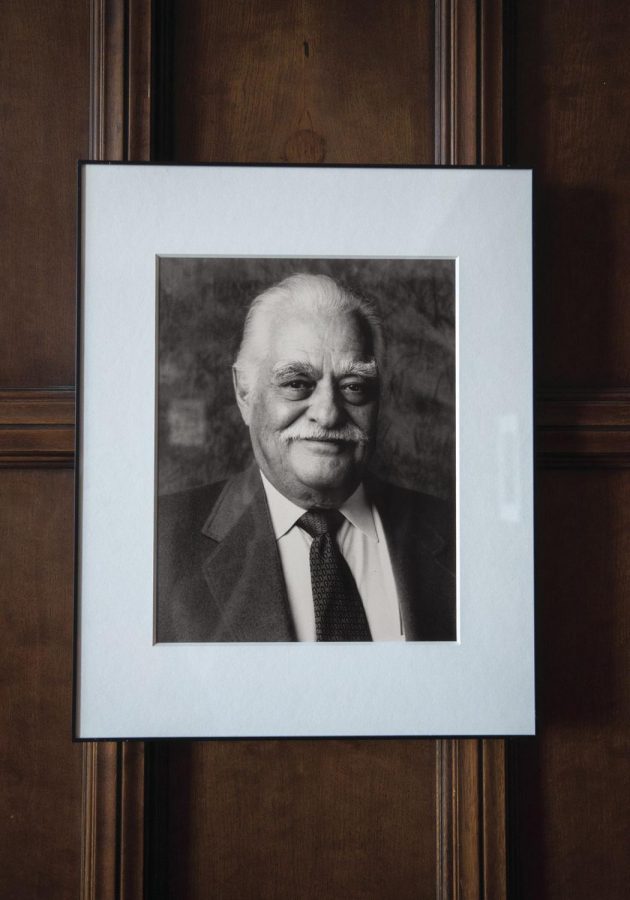

Bert Gall, a 1969 alumnus who studied journalism, worked in the campus bookstore during 1968 and went on to work at Columbia for 34 years. A regular protester and activist, Gall said Columbia was a natural place for people like him because he grew up around activism.

Before walking as valedictorian at commencement in a Viet Cong flag and rice hat in protest of the war in 1969, Gall remembers participating in the Democratic National Convention demonstrations, a week of protests at the end of August that began in Lincoln Park—the neighborhood where the majority of students lived—and shifted to Grant Park, culminating at the John Alexander Logan monument across the street from Columbia’s current Michigan Avenue buildings.

Anti-war protesters arrived at the DNC to challenge the Democratic Party stance on the Vietnam War. Then-Mayor Richard Daley prepared the city by deploying 12,000 police officers and 15,000 state and federal officers to contain the protesters.

Gall said he would not have wanted to be anywhere but Chicago during convention week, describing it as “a time like no other time in our lives.”

“[There was] a lot of gas. A lot of adrenaline. An astonishing display of a police department out of control,” Gall said. “I’m reminded of it when Black Lives Matter talks about police violence in 2018, and yet the origins of police violence go back to 1968. We’ve had a police department out of control for 50 years, doesn’t seem to matter who the mayor is.”

Gall added that faculty also participated in the DNC protests, including the late John Schultz, a creative writing professor who joined the college in 1966 and became the college’s first chair of the former Writing/English Department.

Also protesting during the convention was then-lecturer Staughton Lynd, who was arrested Aug. 28, 1968, and fined $500 for not following police orders to leave a sidewalk at 43rd and Halsted Streets, according to a May 1, 1969, Chicago Tribune article.

Associate Professor in the English and Creative Writing Department Tom Nawrocki spent convention week differently. Nawrocki wouldn’t enroll at Columbia until 1970, immediately following the end of his military service, but in 1968 he was almost faced with confronting demonstrators.

“If you didn’t get into college right away you were going to be drafted, so there were a lot of us who, rather than be drafted into the army for two years, you would enlist so you would have some sort of control over what was going to happen to you,” Nawrocki said.

He became apprehensive about the war after hearing from returning veterans and losing his cousin during the Tet Offensive.

“There was such turmoil in America. I enlisted to be a Marine and defend my country against communism in a foreign country, and in 1968, they started training me to be a riot control officer to go into the American streets and break up riots in American cities,” Nawrocki said. “I would be putting a bayonet in the face of somebody I might’ve gone to school with.”

Nawrocki began riot training following MLK’s assassination and was on standby in North Carolina for the DNC protests. He questioned the war but felt pressured to follow military orders, even as others discussed fleeing to Canada if deployed for riot control. Nawrocki faced a moral dilemma. He said he is happy he was never deployed to Chicago.

“I had to think, if [Marines] refuse to go, then I’m going to have to sign documents to send them to prison,” Nawrocki said. “It’s odd to be put in that position, to carry a rifle with a bayonet on the end and think that you have to put it in an American’s face with hostile intentions. I didn’t sign up for that, but there it was.”

Nawrocki said the divide over the Vietnam War took place largely between older generations who survived World War II and held trust in the government, and younger generations who began to suspect the government was lying about the events of the war.

Andrew Wilson, an adjunct professor in the Humanities, History and Social Sciences Department, said the Tet Offensive was seen as the end of the U.S.’s involvement in the war, but also when people began to see the truth behind the war.

The Tet Offensive was a series of coordinated attacks against U.S. and South Vietnamese militaries by North Vietnam and Viet Cong forces in January 1968.

“It was because of Tet that many people began to see that what the United States had been telling the American public about progress in Vietnam wasn’t actually the case [and] that this war was not going to be over anytime soon and that it was going to cost a lot more American and Vietnamese lives before it ended,” Wilson said.

Chris Broadhurst, an assistant professor of Higher Education at the University of New Orleans, said an influx of student activism during 1968 was due to the emergence of counter-culture among youth that defied societal norms.

“Cities like Chicago, New York or San Francisco had larger centers of resistance,” Broadhurst said. “There were a few [college presidents] that wholeheartedly supported [student activism and] there were some that vehemently opposed any form of activism and disruption. No college president, even the ones that supported the right to voice their views in support of the causes, are going to support disruptions of classrooms.”

However, Nawrocki witnessed Alexandroff’s support even in 1970, when the college shut down in support of anti-war student protests at Kent State University.

“He left it up to the student body and we said, ‘There are other schools that are closing down for a week to protest this action, these killings at Kent State, and there’s going to be protests in the street and we want to join that.’ He said ‘Ok. The school will shut down, we will suspend the classes and there won’t be any penalties.’ I was out on the streets protesting the war with hundreds of thousands of people.”

Norman Alexandroff, Mike Alexandroff’s son and communication coordinator for the Library, said Columbia’s focus in 1968 was creating opportunities for underserved and minority communities and becoming more connected with the city.

Columbia expanded into the Lincoln Park neighborhood with a dance center and The Free Theater, an admission-free public theater run by then-music program director and musician Bill Russo.

Albert Williams, an associate professor of Instruction in the Theatre Department, was a student studying music in 1968 who joined the theater company in 1970. According to Williams, “The Civil War” was a 1968 production directed by Russo that compared the civil war of the 1860s to the divide in America during the 1960s.

“The end of the show was a song about a mother grieving over her son who has been killed in the war and the last lines of the show are ‘The war is a mother that takes back youth,’ and that was repeated over and over again. The audience was stunned, and it launched The Free Theater as a viable theater company to produce other works,” Williams said. “It established Columbia as a presence on Chicago’s cultural scene as the voice of the new, young people.”

The theater was once turned into a makeshift hospital for anti-war protesters driven out by police with tear gas during the DNC protests, which solidified the production’s message, according to Williams.

As part of the college’s community engagement, Mike Alexandroff hosted an “Arts in the Inner City” conference in 1968 to bring together artists and educators from minority and working-class communities from around the country to address a lack of representation of African-American and Latino communities.

When COBRA, the Coalition of Black Revolutionary Artists, unexpectedly took over the conference to protest white power structures that controlled arts funding, the college found itself embroiled in controversy.

“It was the first time there was a black, white confrontation in the arts and because a lot of the foundations were invited, they recognized that they needed to reorder their priorities to serve communities of color,” Norman said. “It was an effort to create some publicity for the college, but it also started a conversation that resonates to this day in terms of minority representation and the need for communities of color to shape their own communities.”

Norman said the social activism of 1968 is embedded into the college’s DNA due to Mike Alexandroff’s commitment to producing socially aware artists and communicators who could lead social action and change.

“In 1967, Martin Luther King had called on Columbia students, faculty and staff to join him at the march in Marquette Park, where other college’s had presidents standing on tanks,” Norman said. “Columbia was organizing marches in support of Dr. King. Columbia was the center of this counter-culture movement in the country and Chicago in particular.”

Issues of 1968 are still fought by students today, using similar tactics, Broadhurst said.

Bert Gall sees movements he participated in reflected in today’s demonstrations.

“I look at the kids in Parkland, who are impressive as can be, organizing against gun violence,” Gall said. “As you look at things like the women’s march in Washington after the Trump election, you think the reach of much of that goes back to the 60s.”

Norman added that Columbia’s relationship with society during the 60s was reciprocal in that the social movements contributed to the college’s growth just as the college’s community helped shape Chicago.

“It’s hard to separate the time and place of Columbia from the 60s, particularly 1968,” Norman said. “Columbia is a byproduct of the time and place and it’s hard to imagine we would have existed or grown in the same way had we not been central to these mass movements of people in the 60s.”