A WHOLE NEW WORLD: International students strive to fit into the Columbia way

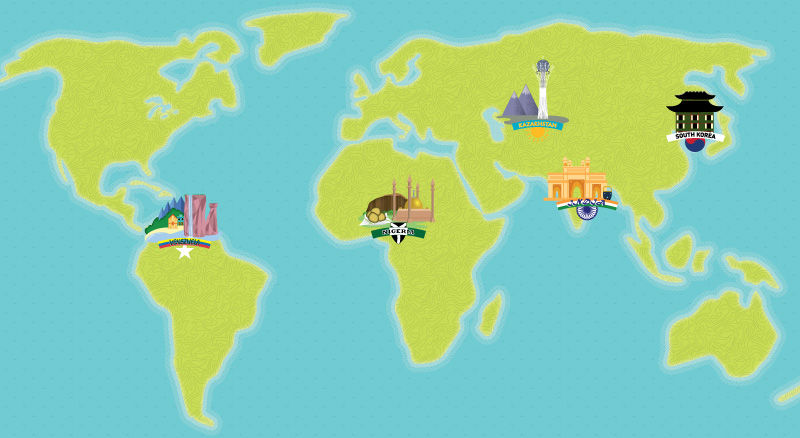

Around the world

February 29, 2016

Lectures, exams and solitary book-cracking—is that the way to learn about art, music and creativity? International students seek out Columbia to do it all differently—with collaboration and self-expression.

For example, SungJin Kim came to the United States from South Korea to attend Columbia because she wanted a place to express her interests in music, photography and art. The senior music major also wanted an education that was more individualized and less regimented than what was available in her home country. In South Korea, the education is lecture-based with more tests and minimal student discussion.

Kim expected Columbia to be a place of collaboration and hoped to enlist other students to produce creative projects outside of class. But, Kim soon found the language barrier and amount of homework made this unlikely. Two years later, she is still unable to work on outside projects with other students and struggles with American culture and slang.

Time is also part of the problem for students and there are still plenty of class requirements.

“We should take less liberal arts classes and do more collaboration,” Kim said. “We don’t have enough time to hang out with friends from different majors.”

Adjusting to college is difficult enough, but even more so when a student comes from a foreign country. The list of challenges includes language and cultural barriers, economic obstacles and compliance with immigration regulations on top of the burden of being thousands of miles away from friends and family.

Kim is one of approximately 400 international students who come to Columbia from 63 countries across six continents, according to Kevin Obomanu, coordinator of Columbia’s International Student Affairs Office. The number of international students has steadily grown throughout the years with an increase of 172 new students for the Fall 2015 Semester.

Most international students come from China—which makes up one fourth of the international population with 88 students, followed by South Korea, Brazil and India, Obomanu said. The Cinema Art + Science Department attracts the greatest number of foreign students, along with the

Photography Department.

Gigi Posejpal, the director of the International Student Affairs Office, and Obomanu assist these students in acclimating to Columbia through workshops, social events and day-to-day advice and counseling.

“If you are going to a different country and you are used to things back home like getting a job or driving—and all of a sudden [you are] going somewhere else where some of those things you cannot automatically do—that’s very difficult,” Posejpal said.

While the office dates back to the 1950s when Columbia started accepting international students, the college began emphasizing greater inclusion in Fall 2013, leading to the creation of a special orientation that starts before Welcome Week. The college also helped restructure a number of programs, including cultural workshops to educate the student body and a buddy system, Posejpal said.

Students receive information about their visa from their home countries before coming to the U.S., but the office recently instituted workshops to help students understand what their visa means. It advises students of the deadlines for filing necessary paperwork to maintain their status and any restrictions. For example, a frequent need is a Social Security number, which is essential to get a driver’s license, state ID or have a cosigner for renting an apartment. Identifying a need for more progress by assisting international students at Columbia, Obomanu took over the Buddy Program—originally created seven years ago by a former international student. The program connects incoming international students with Columbia students to help adjust to the new classes, culture and Chicago’s melting pot. Most incoming students apply for the program, especially ones that are coming to the U.S. for the first time. Obomanu said there were 67 international students who wanted a buddy in the Fall 2015 Semester.

Along with residency and inclusion issues, international students say they frequently experience cultural insensitivity and glaring ignorance about life outside the U.S.

Manuela Alcalá, a senior television major from Venezuela, said she was appalled that some people do not know where Venezuela is on a world map and was once asked if her home country was in Africa. She said she also noticed people in the U.S. judge others based on their financial status.

Alcalá said some U.S. residents label all Venezuelans as poor, based on what they hear in the news, which tends to depict all of Venezuela as having a terrible economy.

“[People] look first at how much you are paying for something and then they decide what kind of person you are,” she said.

Rafael Alvarado, a junior graduate student in the Interactive Arts & Media Department who is also from Venezuela, said he noticed in his two years at Columbia that his classmates were ignorant about South American culture, failing to grasp how countries differed.

“Somebody told me once that I don’t look like someone from Mexico,” Alvarado said. “We are all from different backgrounds and cultures.”

Venezuela faces economic struggles, but Alvarado said he never encountered racial harassment or discrimination to the extent he has seen here. He said it was strange to come to a place where this is still very much an issue, and understanding all the underlying racial stereotypes in U.S. society was striking to him.

“Those kinds of things, they don’t tell you,” Alvarado said. “You kind of have to figure it out when you come here.”

Sarah Olaniran, a junior double major in dance and radio from Nigeria, is known in her home country for dancing in popular music videos and concerts. She said people at the school have asked her odd questions like whether she has pet lions and compliment her on her command of English.

“‘English is our first language in Nigeria so I don’t know what you’re talking about,’” Olaniran responds.

Olaniran said these assumptions about her home country are irritating and wishes her classmates were better educated about other countries and cultures.

Posejpal said she warns students they may be faced with questions by domestic students that may be off-putting or offensive to internationals, adding that media portrayals of other countries shape Americans’ perceptions of them.

“We have to tell international students not to take things personally,” Posejpal said. “Whatever is being communicated is being done through a lens; whereas when you are meeting with an international student, you can have the opportunity to hopefully get the other side of the story.”

On the social side, the ISO offers student clubs, workshops and events so global students can immerse themselves in the Columbia culture and get connected with other students, like the Lunar New Year Celebration on Feb. 12, which featured Asian cuisine, origami and a chance for people to learn about new cultures. Group dinners to a cultural part of the city like Chinatown is also a community event that the group hosts.

“Multicultural Affairs is truly the microcosm of the college,” Posejpal said. “We embody what Columbia is all about. With work that has been done through the LGBTQ Culture & Community, and one of our coordinators being involved in the ‘Practicing Diversity’ series, we are bringing it all together [at Columbia].”

For many students, however, the greatest challenges are financial. The college does not offer scholarships to international students, so they have to pay full tuition. Student visas generally restrict recipients only to campus jobs limited to 20 hours a week and pay minimum wage as well.

Alcalá said she was lucky to work at the TV Cage in the Television Department during the Fall 2015 Semester, but not all students can find employment as easily.

“[With] the amount of money you earn [from Columbia], you are never going to be able to pay rent, bills, groceries, everything,” she said.

Alcalá said she knows some international students at Columbia who work under the table to make ends meet financially, but she has never needed to.

Obomanu said he has heard of students working illegally, although the law prohibits this. He understands the financial struggle with finding a job on campus, and Columbia’s limitation on international scholarships makes it difficult for them not to cut corners. He said there is a misconception that all international students are wealthy, but that is not always the case.

“A good portion of students come from very typical middle class homes where their parents have put together this money for them to study in the U.S.,” Obomanu said.

But Columbia’s rising tuition poses unanticipated budget problems to international families, causing them to worry about raising more money—resulting in some students eventually transferring.

Similarly, ISO faces resource challenges of its own to give international students what they need to succeed. The Learning Studio, 618 S. Michigan Ave., houses The Writing Center where students can go for writing and language assistance. However, it only offers two English tutors to international students. Posejpal said this poses a big problem given the influx of international students who need language assistance. Having more tutors, mentors and staff members, along with financial resources to fund programs, are ways Posejpal says the college can improve in helping these students feel at home at Columbia.

“Being able to work with faculty and providing them with support so they can do what they need to do effectively [is crucial],” Posejpal said.

She said she has used resources from another department, but the college is in the process of developing a Global Education Professional Development series that has support from the Provost’s Office and will begin in Fall 2016 to include more programs beneficial to international students.

Despite the hurdles faced by international students, many express satisfaction with the education they receive at Columbia.

Terry Travasso, a senior photography major from India, said the photography program has given him an excellent education, exposing him to advanced photography classes and allowing him to make connections that span the country.

“The people I met here in the photo department are amazing. I love collaborating with different people,” Travasso said. “It helps you network and create bonds for the future.”

Yana Tyan, a senior advertising major from Kazakhstan, said she came to Columbia because she wanted a more creative education. Art school culture was a different U.S. college experience for Tyan, but that was part of Columbia’s attraction, she said.

“No one is afraid of expressing their opinion,” Tyan said. “Sometimes I have different perspectives because I am from a different country, but people are still very supportive.”

While music major Kim is still disappointed by the lack of collaborative opportunities, she is very happy with the diverse student organizations on campus and the community’s self-expression, which is refreshing for her to experience. She said her tuition gives her an incentive to participate and interact with Columbia’s mixed student body and resources. She feels her education is quite the opposite of strict.

“Everybody is creative and there are no limitations or rules,” Kim said. “You can do whatever you want to do—your identity is respected.”