Everything you need to know about the Electoral College in 2020

August 6, 2020

With less than 100 days until the November general election, the Electoral College is once again creeping into the political conversation, even though it’s something many Americans likely know little about.

How does the Electoral College work?

Prior to the general election in a presidential year, each state’s political parties nominate a group of “electors” who pledge to vote for a party’s candidate. The number of electors from each state party is based on the number of the state’s congressional representatives, plus two electors for senators. The number of representatives in each state is based on population, which is counted every 10 years in the census.

For instance, Illinois—which has swung Democratic in recent presidential elections— has 20 electoral votes of the total 538 electors nationwide, although a candidate only needs 270 electoral votes to secure the nomination. Democratic electors include Mayor Lori Lightfoot, Rep. Jesus “Chuy” Garcia (D-Ill.) and Ald. Silvana Tabares (23rd Ward), who is also a Columbia alum.

Typically, these electors are “local party faithful” in an honorary position, said Randall Calvert, Thomas F. Eagleton professor of public affairs and political science at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

Party slates of electors are then submitted to their local Secretary of State. On Election Day, voters in all states—except for Maine and Nebraska, where a different system is used—will see President Donald Trump and presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s names at the top of their respective tickets. But what they are actually voting for is the slate of electors who pledged to vote for whichever candidate they choose.

Based on which candidate wins the popular vote in the state, the Secretary of State is expected to submit the corresponding party’s electors to cast their official votes in the election. Those votes are what actually elect a president and vice president.

What about “faithless electors”?

What if an elector goes rogue and does not vote for the candidate who won the most votes? This can happen but does not happen often and it usually does not affect the national outcome in any serious way, Calvert said.

These are called “faithless” electors, or electors who cast a ballot contrary to who won in their state. In 2016, there were seven so-called “faithless” electors. Five of them were faithless to Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton by not casting their electoral vote for her even though she won the popular vote in their states. Two did the same to Trump. Over the past few decades, there has only been around one faithless elector per presidential election.

However, a Supreme Court decision made this term could prevent as many electors from casting a ballot contrary to their state’s voters.

In the July 6 decision in the case Chiafalo v. Washington, the court unanimously voted to allow states to remove or sanction any electors who vote contrary to a state’s voters. The case stems from 2016 when three “faithless” electors in Washington voted for Secretary of State Colin Powell in an attempt to sway electors away from Trump. They were each fined $1,000.

“Here was a great example of the Supreme Court doing the right thing,” Calvert said.

But the court’s ruling does not necessarily guarantee a clean election this fall.

What may happen in November?

Edward Foley—the Charles W. Ebersold and Florence Whitcomb Ebersold Chair in Constitutional Law at Ohio State University—is concerned this year’s election will look more like the “most disputed presidential election in American history” between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden in 1876.

The election was decided in Republican Rutherford’s favor by only one electoral vote and caused conflict in Congress before the inauguration as congresspersons sparred over who would become the next president. The confusion over who won was due to both major parties in four states—Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina and Oregon—claiming they won their state’s popular vote.

The risk of a situation similar to 1876 happening in 2020 is higher than it has ever been, Foley said.

With so many states depending on mail-in ballots because of the coronavirus pandemic, it may be more likely that both parties could claim a win in a particular state, leading to legal disputes tied up in the courts that could take a long time to resolve, Calvert said.

Others have disputed whether voting by mail will cause such a disruption.

If there is no clear winner, the 12th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution would come into play. The amendment sends the decision to the U.S. House where one representative for each state casts a vote for any of the top three candidates with the highest popular vote.

Although there is a Democratic majority in the U.S. House, red states individually would outnumber blue ones in this scenario, Calvert said.

“This year in particular, it’s going to be really important whether the vote overall in the country is a close vote or a lopsided vote,” Calvert said.

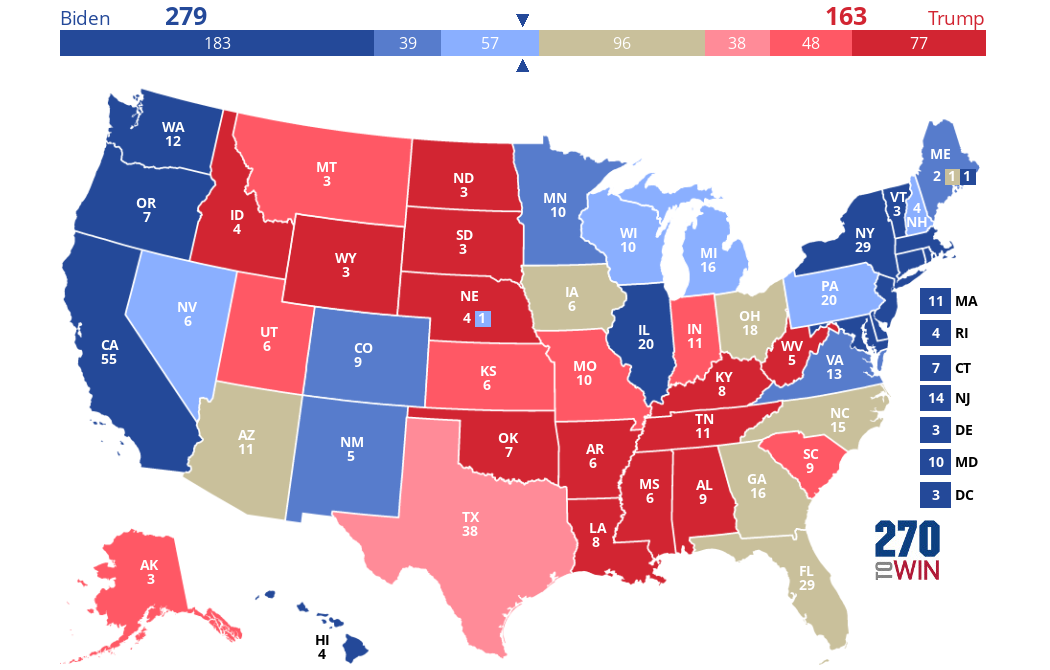

Click the map to create your own at

Click the map to create your own at