Textbooks or lunch? College students struggle for daily meals

Textbooks or lunch? College students struggle for daily meals

April 16, 2018

In the nation’s higher education institutions, some students use their free time harnessing their creativity to craft art projects, music or films. Others try various ways to earn money for food by selling their blood, said Anthony Hernandez, a third-year doctoral educational policy studies student and research assistant at the Wisconsin HOPE Lab.

With skyrocketing tuition, fees, textbook prices and more than $1.5 trillion in college student loan debt, young minds hungry for an education also find their stomachs craving an adequate meal, according to a 20-state survey of 40,000 college students by the Wisconsin HOPE Lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison released this month.

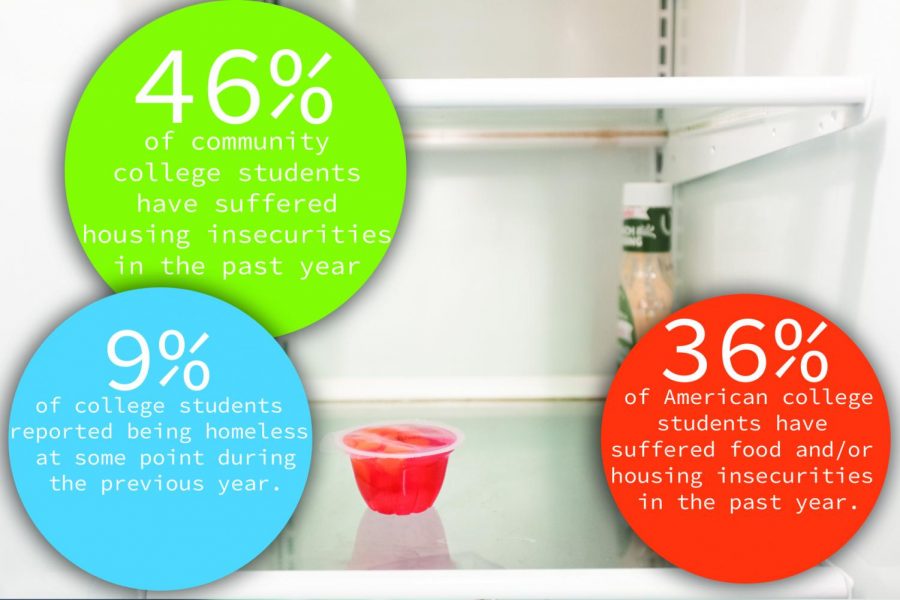

Thirty-six percent of college students said they are food and/or housing “insecure” and 9 percent reported themselves homeless during the previous year. The alarming numbers are even higher among community college students, with 42 percent struggling to find a meal and 46 percent unsure whether they will have shelter at night, according to the survey.

All the researchers were “alarmed” by the survey’s results, said Hernandez, who co-authored the report. The stronger the obstacles to basic filling life needs, the greater the challenge for college students to complete their education. The survey supports the idea that college is too expensive, he added.

“There’s a stress that students experience, and it can be harmful not only to your mental health, but it could be harmful to your physical body,” Hernandez said. “When you’re not eating meals regularly and have poor nutrition, your body and mind pay a price. If you’re in that state, you cannot be your best possible student.”

Hernandez said students told him stories of how their financial struggles caused distractions in the classroom.

“They were thinking about ways to navigate different domains of hardship,” Hernandez said. “They were making calculations. They’re trying to survive. There were students who would skip meals.”

Some students said they have even resorted to dumpster diving and sharing scraps with friends to save money.

This practice has become common among Taylor Jensen’s community. An elementary and middle school education junior at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, Jensen said she has never dumpster dived herself but was unknowingly served pizza from a dumpster by a friend.

Jensen attended Columbia during the 2014–2015 academic year and would often share a bucket of onion rings from Devil Dawgs with her roommate and count it as a meal, she said.

Although the number of students reporting food and housing insecurities was surprising to the researchers, Jensen said she thought it would be higher. A friend of hers was homeless in summer 2017 because she could not afford the area’s housing prices and resorted to sleeping in a hammock in a ravine near campus.

This is the research lab’s third report on food and housing insecurities among college students, Hernandez said. The surveys are gaining more institutions’ attention, which has led colleges and universities alike to create food bank programs at their respective campuses.

“We’ve seen some institutions like the University of California conduct their own survey in their own college campuses,” Hernandez said. “Now that the word is out, administrators want to know what’s going on in [their] orbit, [and] what’s going on with [their] students.”

Columbia has also taken notice of students’ hunger struggles and created its own food bank, which is available to all enrolled students on a walk-in basis at the 623 S. Wabash Ave. Building.

Columbia Care Packages, which was launched two years ago, is funded in various ways, including fundraising events and donations. Most of the students who use the program are referred by faculty or other students, according to Associate Dean of Student Life Kari Sommers.

While some students in need may not know of the program, others could be too embarrassed to use a food bank, Sommers said.

“We have to do everything in our power to make sure our students succeed,” Sommers said. “There’s complex issues and challenges a student might have, and sometimes they’re basic challenges. None of us know what’s going on in someone’s private life. Whatever support we can offer, that’s what we want to do.”

Each Wisconsin HOPE Lab survey has raised awareness about the issues of food and housing insecurities among college students, Hernandez said. But there are still prejudices to overcome, such as myths surrounding college students’ work ethic and financial needs, he added.

“Many people share the idea that you can go to college, it’s affordable. Work during the summers, eat ramen, sleep on the couch; those stereotypes just don’t ring true with the experiences that we’re hearing,” Hernandez said. “You can’t just work over the summer to afford to go to school now. Many students that we talked to are working multiple jobs.”

Another method to address this issue is with what is called a “single-stop model,” in which institutions provide incoming students with a holistic assessment to determine their needs and connect them with social service organizations, according to Hernandez.

This approach allows college students to harness all available resources, preventing a crisis, Hernandez said.

“As an administrator, you would want to know those problems exist, and you would want to try and fashion solutions so those students can be thriving,” Hernandez said.

While it is the humane approach, Hernandez said it is in higher education institutions’ best interest to address food and housing insecurities among their students because it will benefit their graduation rates.

“[Addressing these problems] is about college completion. Who’s against that?” Hernandez said. “Administrators should embrace that. When you help students by taking care of their needs, you’re going to drive the results that you want [to see in the end]. And as a society, then we can have an educated citizenry.”