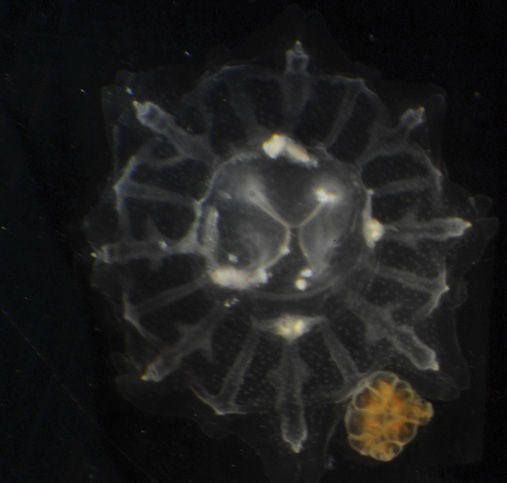

Don’t eat the peanut butter jellyfish

Peanut Butter Jellyfish

February 10, 2014

Not to be mistaken with the lunchtime classic, the world’s first peanut butter jellyfish has been created by an aquarist and an aquarium supervisor at The Dallas Zoo and Children’s Aquarium Aquarist Zelda Montoya and Aquarium Supervisor Barrett Christie fed peanut butter-enriched brine shrimp to a group of jellyfish simply to see if it could be done.

“It was an idea I had quite a while ago as a joke,” Christie said.

The idea was put on the backburner for a couple of years, Christie said. But when papers were published elsewhere detailing a shrimp and fish aquaculture in which the fish were fed a peanut meal in place of the regular shrimp diet the idea resurfaced, Montoya said.

The study, published in January in Drum and Croaker, a non-peer-reviewed, informal journal for public aquarium professionals, took things a step further when the jellyfish were only fed emulsified peanut butter in the seawater.

“[This] is a better test because we’re seeing if they will grow only on this peanut butter-based protein, only on this vegetable protein instead of the brine shrimp protein,” Christie said.

Results showed the jellyfish did not initially grow as fast as they would by eating their normal diet, but they grew over time as they would had they been fed brine shrimp, Christie said. The next step is to see if the jellyfish breed and produce second-generation peanut butter jellyfish.

“[This] would be the ultimate proof that this [diet] does actually meet every one of their nutritional needs,” Christie said.

The aquarium jellyfish are usually fed a shake of brine shrimp and other proteins, Montoya said. Jellyfish are carnivores and feed on small prey such as plankton and krill. They use the stinging cells embedded in their tentacles to fire neurotoxins into their prey, according to Simon Alford, professor of biological sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“They’re not like a saber tooth cat running across the prairie and chewing on things,” Alford said. “[But] if it’s a high protein diet, for whatever reason they take it up.”

The jellyfish did not initially show any changes from eating the peanut butter other than getting food into their systems, according to Montoya. But after a week, the jellyfish started to grow.

“We were noticing exactly what we would expect from a jellyfish as their size continues to grow and [become] actual jellyfish,” Montoya said.

The study also altered the environment in the aquarium and created a bit more work for Montoya. The water became dirtier because of the emulsified peanut butter put into the water to feed the jellyfish and required more frequent water changes.

Maintaining a clean aquarium is an issue when keeping and breeding jellyfish, Alford said.

“The animal is going to eat and it’s going to excrete and that all ends up in the same water,” Alford said. “You’ve got to keep replenishing seawater and you’ve got to have bacteria in your filter pumps that deal with seawater instead of freshwater.”

Replenishing seawater is difficult for the aquarium because Dallas is land-locked and artificial seawater has to be made, Christie said.

“Adding the peanut butter into the water will foul the water quite quickly if it’s not removed,” Christie said. “We have to be very careful about the water chemistry of all our tanks, especially [with] something as delicate as jellyfish.”

Overall, the peanut butter has not completely fouled the water and has proved to be a satisfactory diet, Christie said. It will not be incorporated into the normal jellyfish diet any time soon, but Montoya and Christie are working with the zoo’s nutritionists to try to conduct some controlled studies that will observe how much nutrition is actually in the peanut butter samples. The results would determine whether the peanut butter diet could be implemented into the daily jellyfish meals.

“It kind of opened up a novel source of food to us,” Christie said. “It gives us an avenue to pursue.”