Editors’ Note: Journalists are documenting history, let them do their jobs

June 8, 2020

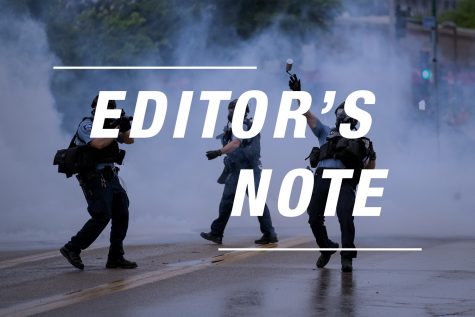

While broadcasting and covering a peaceful protest in Minneapolis, Canadian field correspondent Ali Velshi and his MSNBC camera crew were shot at with rubber bullets and tear-gassed by police.

Linda Tirado, a photojournalist based in Nashville, Tennessee, is now permanently blind in her left eye after being the target of rubber bullets from police while on assignment.

While covering peaceful protests, riots and demonstrations, dozens of journalists have been arrested, attacked and scrutinized for doing their jobs.

In a May 30 statement in response to reports of attacks on journalists by police officers and protesters while covering demonstrations across the U.S., Carlos Martínez de la Serna, the program director for the Committee to Protect Journalists, said the attacks show “a complete disregard for their critical role in documenting issues of public interest and are an unacceptable attempt to intimidate them.”

The American Civil Liberties Union, or ACLU, filed a class action lawsuit against Minnesota authorities on behalf of journalists who were beaten, shot at, tear-gassed and arrested by Minnesota police officers.

The lawsuit stated: “This pattern and practice of conduct by law enforcement tramples on the Constitution. It violates the sacrosanct right to freedom of speech and freedom of the press that form the linchpin of a free society. It constitutes a pattern of unreasonable force and unlawful seizures under the Fourth Amendment. And it deprives liberty without a modicum of due process protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.”

But the violent attacks are not even the worst part. Officers and protesters are preventing journalists from informing and educating people as transparently as possible.

Even as student journalists, we often run into a similar issue on a smaller level with our campus coverage, receiving pushback on what we cover, how we cover it and our use of transparency.

Ed Yohnka, director of communications and public policy at the ACLU, said while people are protesting police violence, they are also being met with violence from the police.

He said journalists who are clearly identified as members of the press are being targeted, which “must be challenged,” because limiting a journalist from doing their job is harmful.

“We are a nation that values the first amendment, and both the ability to protest and the ability of the press to cover those protests and other governmental actions,” Yohnka said.

The fact of the matter is, as journalists, our sole purpose is to report on events, issues and topics that are of interest or concern to our readers.

Journalists are not out covering protests or demonstrations to exploit anyone or offer a particular narrative. We are here to document history, to amplify voices and to objectively deliver a report of events.

It is not our job to please or placate anyone, even though that is a natural instinct. It is our job to make sure that atrocities and everyday injustices do not get swept under the rug or go unheard.

Just like in any other profession, as journalists, we should be forced to critically examine our personal biases and shortcomings, admit when we are wrong and make a commitment to better ourselves.

However, know we are scrutinizing every photo, every paragraph, every word we publish for accuracy and to make sure it minimizes harm to the people and communities we are covering.

We are holding ourselves accountable as much as you are.

For some, activism may look like donating to a cause, educating oneself and others or protesting in the streets. For journalists, our activism exists through our work, whether that means having sources explain their reasons for marching, providing resources for those looking to donate to various causes or being a source of information and perspective.

In any case, we are on the ground with you, contributing to movements in a different way. On a daily basis, we use our platform to call for accountability and in some cases systemic change by gathering evidence and seeking and reporting the truth, even when it may not be comfortable to read.

‘We kind of lost sight, in the blinding division of society, that at some level part of journalism is just to tell us what is happening, not necessarily what we want to hear,” Yohnka said.