Accumulating points or knowledge: Do letter grades miss the mark in assessment?

Accumulating points or knowledge: Do letter grades miss the mark in assessment?

April 29, 2018

On the day of a final exam, Thomas Guskey asked an intelligent 14-year-old girl in his Erie, Pennsylvania, science class whether she had studied for it.

“No,” she replied.

“Why?” Guskey responded.

“She looked at me really quizzically and said, ‘Mr. Guskey, I worked it out. I only need a 51 percent to get my A. I don’t need to do better than 51 percent,’” said Guskey, who is now an educational psychology professor at the University of Kentucky specializing in grading and assessment. “This 14-year-old had worked it out to the tenth decimal place what she needed to do to get her A.”

Guskey was shocked. He had his 8th grade class take final exams to better prepare them for high school-level coursework, and he couldn’t understand why one of his brightest students would not want to strive for excellence, he said.

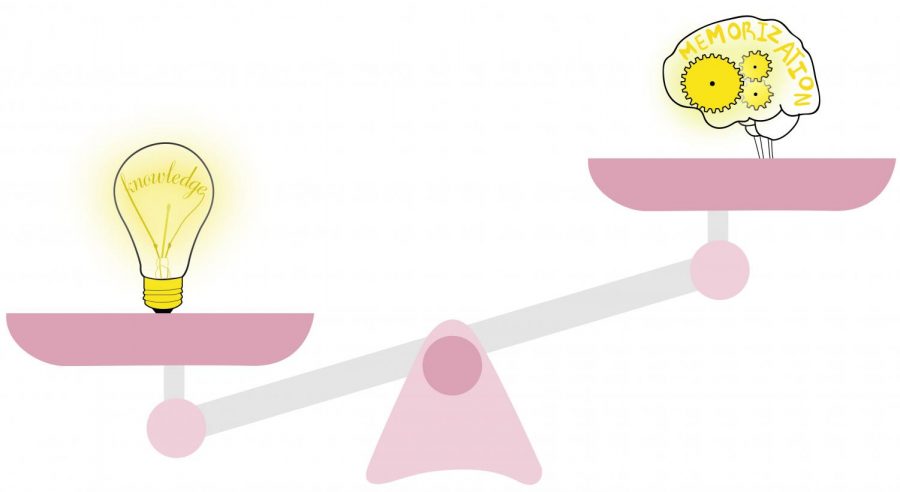

Such incidents suggest that teachers are trapped in a grading system built on accumulated points to calculate a percentage average.

With an emphasis on achieving a high GPA rather than acquiring knowledge, the traditional American grading system encourages students to prioritize grades over learning outcomes, according to education psychology and policy experts.

Those experts suggest the system presents inaccurate assessments, inflates grades and fails to reflect students’ learning outcome proficiency. And once students have caught on, they learn how to “game” the system by focusing on points rather than knowledge.

“It develops students as grade grabbers, not as learners, because everything they do gets scores, and every score becomes part of the grade,” said Ken O’Connor, an independent education consultant who advises school districts on grading and reporting systems.

This approach causes students to do the bare minimum and avoid challenging themselves, O’Connor said. Often, students will assess their own grades before a final exam to determine what they need to pass the class or get their target grade and do no more than that. These strategies do not prepare students for the working world, which favors competency and proficiency, O’Connor noted.

Even the highest achievers appear to be motivated by grades regardless of whether the grade translates to proficiency or even mastery of a subject, according to a June 2014 study by CBE Life Science Education, a life science education group.

Alternatives to conventional grading are being tested in elementary and secondary education and have begun to filter into higher education institutions. At least 10 colleges or universities have adopted variations of pass-fail systems or provided students with alternative assessment models.

Brown University, for example, allows students to choose between two grading systems: a conventional grading system but only grades A, B and C are used with no minus or plus signs, or a “satisfactory/no credit” system, that allows students to request written evaluations, according to the university’s website.

Traditional letter grades, based on points and percentages that are averaged by the end of a semester or term, are not an effective method of assessing the actual retention of a students’ knowledge, O’Connor said, adding that points-based grading undermines the ultimate goal of education: to develop a student’s knowledge to help them accomplish to whatever endeavor they choose.

At higher education institutions in which a final grade is heavily dependent on a final exam, students realize that they can neglect much of their work throughout a semester but still pass their courses as long as they receive a high enough score on their final exam.

“As a friend of mine once said, ‘Any game you set up, students will learn how to play it,’” said Susan Brookhart, an independent educational consultant and senior research associate in the School of Education at Duquesne University. “If you set up a game where students can get into a situation like that, you are setting them up to do bad things. It may work in the short run, but it certainly doesn’t work in the long run.”

This practice, if successful, will encourage students to continue to cram information the night before a final exam, O’Connor noted, and could potentially follow them when they enter into the workforce.

Despite the point system’s drawbacks, Guskey and O’Connor agree change is unlikely because so many school systems rely on it. But a student’s grades could also be inconsistent or inflated, especially when behavior is calculated in the assessment, O’Connor said.

“The lovely young person who smiles sweetly and does everything they’re asked for often gets inflated grades,” O’Connor said. “The problem with that is those inflated grades may get a student into college. But, almost inevitably, they will then fail in college because they were promoted beyond their level of capability.”

It can also create a reverse effect for students with high academic potential by deflating their grades because they do not behave properly, O’Connor said.

“People who were brilliant who could have done great things for themselves and society end up dropping out because they got grades that understated their achievement,” O’Connor said.

According to the CBE Life Science Education study, grades can be inconsistent both within an individual instructor’s grading and in comparison with grades calculated by colleagues. Ethnic, racial and gender biases can also influence grading. The study cited a survey in which 142 teachers were asked to grade the same English paper, and the grades ranged from 50 percent to 98 percent.

There is also no precise method to calibrate grades so modest, incremental differences are greatly meaningful, O’Connor noted.

“Nobody in a meaningful way can tell the difference between a 72 percent and a 74 percent,” O’Connor said, “or, more importantly, between a 89 percent and a 90 percent, which is often the difference between an A and a B. They appear to be precise, but they’re not.”

Some higher education institutions have adopted pass/fail systems for first-year freshmen, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Wellesley College. This allows students to adjust to college and live away from home for the first time without the burden of grading, O’Connor said.

But Brookhart cautioned a pass/fail system may also cause students to only do the bare minimum and avoid intellectually challenging themselves.

Brookhart encourages more one-on-one feedback from teachers to students, even for assignments that won’t be graded. However, providing students feedback creates another challenge for teachers and institutions: class sizes.

“If you have 200 people, you need help [providing] that feedback,” Brookhart said. “Teachers [who are] not giving feedback are not falling down on the job. Some of them who are not giving feedback don’t realize how important it is.”

Standards-based grading is an alternative system that is gaining ground, O’Connor said, and he would like to see it applied more often in higher education institutions.

A standards-based grading system separates achievement and behavior and bases grades on learning goals, competency and proficiency instead of points and percentages to calculate a letter grade. This system helps eliminate the problem of inconsistent grades, according to O’Connor.

In this model, grades are based on demonstration of proficiency toward learning goals. Students attempt standards-aligned activities, such as projects, quizzes and essays, and instructors assess a student’s output and identify the appropriate proficiency level demonstrated.

Typical scales in standards-based grading have four levels of proficiency to reflect students’ increasing skill. 1s indicate that students have little understanding of a subject, 2s are for when students show partial proficiency, 3s are when target goals are met, and 4s are used when a student excels beyond goals.

However, some educators and education administrators value the traditional grading system’s efficiency and argue that the standards-based system doesn’t solve the problems of inconsistent grades and brings problems of its own.

The final letter grade a student receives at the end of a term should reflect their overall learning outcome, said Neil Pagano, Columbia’s associate provost for Accreditation and Assessment. But there will always be grade fluctuations in the same assignments between teachers no matter the system used, he added.

“We’re human, and it’s very difficult to calibrate everyone’s standards 100 percent,” Pagano said.

There is a potential for abuse by higher education institutions with a grading system based on competency and proficiency rather than points and percentages, Pagano said. It can also be difficult for an institution to demonstrate that its process to assess student competency is reliable and its graduates have achieved it, he added.

“Students would go apply to an institution, and the institution would say, ‘Alright, I’m going to sit down with you and see what you can do.’ There’s potential for the institution to exaggerate the competency of the student applicant and give them credit for competency,” Pagano said. “It becomes messy, and the default position is to go back to what we’re all used to, which is letter grades.”

Letter grades also have efficiency standards built around them to calculate a GPA for a reason, Pagano said. Much of the features and awards for letter grades, such as dean’s lists, help students apply to post-undergraduate school programs, which are based on GPA. If a student achieves a bachelor’s degree without a GPA or letter grades, it could become a challenge to apply to graduate school, he noted.

Having that mark of high achievement, such as a high GPA, is significant to Maneet Mander, a 22-year-old interactive arts and media major. Mander wants to apply to graduate school, and having a high GPA will help her when she applies and motivates her to do coursework, she said.

“[What] motivates me to keep [my grades] high is the opportunities after,” Mander said. “Not that opportunities are limited to your GPA, but certain doors are open to you because it’s not just, ‘Oh, you got good grades,’ it’s, ‘Oh, you’re dedicated. You put in a lot of time and effort and you care enough to keep your grades high.’”

But O’Connor and Guskey insist that the problems that accompany alternatives to traditional grading systems are not insurmountable.

“If teachers are working with a limited number of levels, they’re found more consistent with their judgments than with percentages,” O’Connor said. “Ultimately, they’re more accurate and fairer for students.”