Dwindling numbers of native students at Columbia results in lack of representation

April 19, 2019

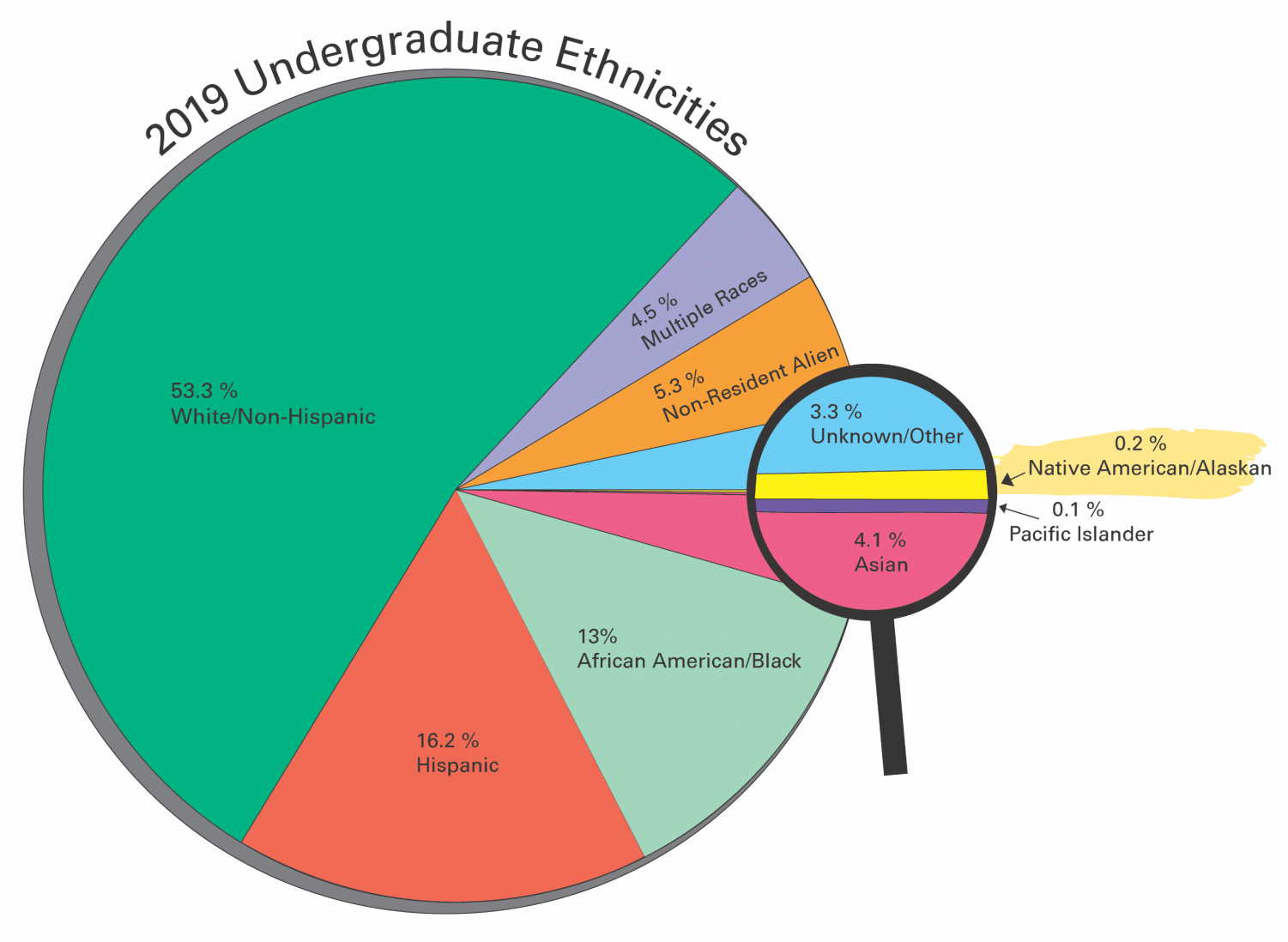

Native American students are few and far between at Columbia, a college that advertises its diversity. As of Spring 2019, there are 11 American Indian/Alaskan undergraduate students enrolled, according to Institutional Effectiveness.

Junior illustration major Gabriel Marin is one of those 11. Marin understood there were not going to be many Native American students at Columbia when he transferred from Marquette University in Wisconsin, but he said he is frustrated with how few there actually are.

“No wonder I couldn’t find anybody else. There’s 10 other people,” Marin said.

Raquel Monroe, associate professor of dance and co-director of Academic Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, said DEI is aware of low enrollment among Native American students, but said low numbers are a problem at higher education institutions nationwide.

“That’s absolutely something we would look into at the DEI office,” Monroe said. “The DEI advisory committee is our way of thinking about how to get more people involved in those types of issues in terms of recruitment and developing programs.”

The DEI advisory committee was created to develop DEI initiatives beginning in fall 2019. The committee will be comprised of full-time faculty, part-time faculty and staff, as well as students and administrators.

“It’s really frustrating that Native [American] students don’t really get support like the other students do,” Marin said.

As a transgender student, Marin is more comfortable at Columbia than he was at Marquette—a Catholic Jesuit university—because the college has a more welcoming environment. However, some instructors have used outdated terms to identify Native American people and culture, he said.

“Sometimes a teacher will say Indian instead of Native American or Indigenous people, and that can get annoying,” Marin said.

Native American students are one of the few ethnic groups without an organization or club at the college.

Although the college provides an inclusive environment, Eurocentric courses are dominant, Marin said. Students would be interested in courses on Native American culture, and it would be beneficial to have Native American instructors teaching those subjects, he added.

Professor in the English and Creative Writing Department Karen Osborne, whose expertise includes Native American literature, said more Native American faculty and courses would attract more Native American students.

“When students see people they identify with, that inspires them,” Osborne said. “We could have a program in Native American studies, but you have to have a Native American faculty member heading that kind of a program.”

In an April 19 email to The Chronicle, Academic DEI Co-director Fo Wilson said the college is working on recruiting more diverse faculty and students. However, she added that before the college can recruit more Native American students, it must increase consciousness and offer coursework that honors the history of Native Americans and their presence in the city and country.

“We are working on that, bringing more equity and breadth to our curricular offerings with DEI initiatives that include building a common understanding and language around what DEI in curriculum means at our college as a first step. This goes beyond content and inclusion, using more transformative

Dwindling Native American enrollment at the college has coincided with overall enrollment declines. In 2010, there were 46 Native American undergraduate students and four graduate students at the college. Since then, Native American enrollment has dropped each year.

Cheryl Crazy Bull, president and chief executive of the American Indian College Fund, wrote in a June 17, 2018, article for The Chronicle of Higher Education about the factors that contribute to low enrollment at schools nationwide.

“Many students tell us they feel invisible or unwelcome at mainstream colleges, and we have no reason to believe this will change until those institutions take steps to remedy systemic and institutional racism,” she wrote. “This, coupled with financial need, may be the reason for low college enrollment and degree-attainment rates among Native Americans.”

During a March 14 DEI forum, President and CEO Kwang-Wu Kim said he invited Native American rap artist and Columbia alumnus Frank Waln into his office just before he graduated in 2014 to ask him about his experience. Waln told Kim he liked Columbia, but said it is not a good school for Native American students because the college failed to recognize a different tradition.

“I have been thinking about that a long time,” Kim said. “I realized we [have] got to do it right.”

Before he began his tenure in 2013, Kim was the dean and director of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts at Arizona State University.

Arizona State University has one of the largest populations of Native American students in the country, but the attrition rate—students who drop out before completing a degree—for those students is more than 50%, according to Kim.

“It is a classic model of what doesn’t work in this space, which is to spend all of [one’s] energy focusing on getting people to come and not thinking at all about ‘what are [we] providing?’” Kim said.