Dismantling the definition: Columbia student spreads message of ‘your disability doesn’t define you’ through clothing brand

March 1, 2023

Columbia student Abad Viquez was born with sacral agenesis, a rare condition that causes an absence of a tailbone.

Doctors told his family they were not sure if Viquez would live past birth. Now 21, Viquez is a junior and studying journalism and sports communication.

“They told my parents that I had less than six months,” he said. “They said I wasn’t going to be able to walk, talk, hear or do anything. For me to be here, it’s just a blessing, and I just thank God because I’m here today.”

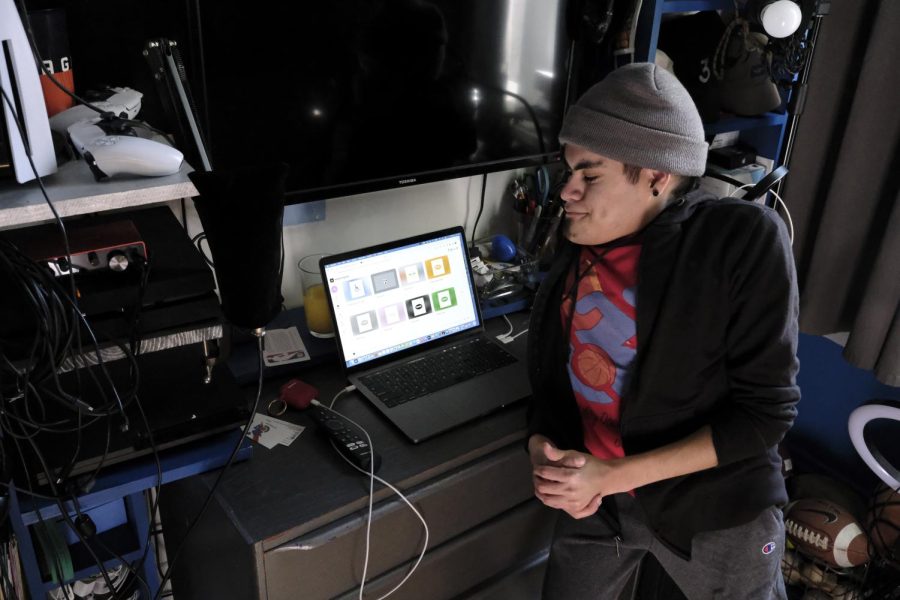

Viquez has used his experiences to create a media platform and clothing brand, YDDDY, which stands for, “Your Disability Doesn’t Define You.” He sells branded T-shirts and hoodies, hats and accessories, all of which he designs himself.

YDDDY empowers other people with disabilities to find their voice and not be singularly defined by their disability, Viquez said.

Viquez started YDDDY in 2019 during his senior year of high school. He donates all proceeds to the Free Wheelchair Mission, a nonprofit that provides wheelchairs to people around the globe.

“The whole goal of this is to let people know that your disability doesn’t define you,” Viquez said. “As soon as people see us, they think that [we] can’t do this and that … I want people to treat me and other people the same.”

While Viquez has some mobility, most days he uses a power wheelchair to get around and to manage the pain in his back and legs. Although there are surgeries to minimize his pain, they risk his ability to walk — something that Viquez doesn’t want to jeopardize. He often plays basketball to tune out stress in his life.

Although Viquez’s clothing line focuses on raising awareness around disabilities, rather than accessibility, Reyes Witt, practitioner in residence in the Fashion Department, said many inclusive brands are shifting to bring adaptive clothing mainstream.

“Inclusive brands are shifting their stereotypes, bringing adaptive clothing into the mainstream,” Witt said. “Global, national, and niche brands are experimenting in this growing category,” expected to reach $400 billion by 2026.

Witt said Major brands like Nike, Tommy Hilfiger and Skims are leading the way in development, but there is still a “substantial void” in product development in adaptive fashion.

Going in and out of surgeries and physical therapy sessions has caused both mental and physical challenges for Viquez. This has been difficult for him to navigate, especially while he’s been in school.

“I try to stay positive because I don’t want people to look at me and start feeling bad about me,” Viquez said. “Like saying, ‘Hey, look at that kid; he’s in a wheelchair. I feel bad for him.’ No, don’t feel bad for me.”

Viquez, who has undergone 23 surgeries, said using a wheelchair comes with privilege as both power and non-power chairs can be tens of thousands of dollars. He said it is like buying a car.

“I feel like things that are a necessity — wheelchairs and medical [expenses] — shouldn’t have to be that much money,” he said.

Abad’s mother, Rebeca Viquez, said although their family has good insurance, it doesn’t cover all the expenses that come with medicine, wheelchairs and transportation. Both Rebeca Viquez and Abad’s father, Carlos Viquez, work multiple jobs to afford what insurance does not cover.

“That’s the only thing that you can do: work and work,” Rebeca Viquez said.

Growing up, it was hard for Viquez to not feel defined by his condition.

For a long time he avoided talking to his parents about the bullying he faced at school and online until a particularly traumatic incident during fifth grade when another student put a pair of scissors and a written note in his backpack telling Viquez to kill himself.

“I was afraid to go to my mom and tell her what happened to me in fifth grade,” Viquez said. “And that was really the first time that I told my mom that I was going through something.”

Once his family knew everything he was dealing with, his parents wanted him to be more involved in school. They signed him up for a theater program that paired students with and without disabilities together in a production. This helped him be more comfortable and confident in his body.

“I said my lines and at the end, as soon as everybody started cheering for every single one of us, I felt like this is the first time I’ve ever felt something like that, where hundreds of people are cheering for me,” Viquez said. Later, in high school, he competed in the August Wilson Monologue Competition. He returned home with a first place award and a ticket to compete in New York at nationals.

“It was acting that changed my life because from there, that’s when I wanted to do my brand,” Viquez said.

Rebeca Viquez said that supporting each other as a family is the best way to make it through life’s struggles.

“I always tell him that the only disability that can make you stop is the disability that someone can put in your mind,” Rebeca Viquez said. “To be honest, I don’t know where we would be without God. But I will just say that love, the love of the family, is the best medicine.”

If he could go back and tell his younger self how to deal with the negativity from others, Viquez would tell himself to use his voice and speak to those he can trust.

“Forget about the negativity and focus on who you are and surround yourself with good people and the right people.”

You can find more information about Viquez and YDDDY on his Instagram page: @yourdisabilitydoesntdefineyou.