Chicago’s segregation costs billions, stunts society growth

Chicago’s segregation costs billions, stunts society growth

April 10, 2017

The Chicago region’s high levels of segregation costs the area billions of dollars in economic growth in addition to creating a less-educated public and leading to hundreds more homicides, according to a March 28 study from the Metropolitan Planning Council.

In conjunction with the Urban Institute, the Chicago-based public policy research group studied three types of segregation patterns in Chicago and the seven surrounding counties: economic, African-American-white and Latino-white segregation in 100 of the most populous metropolitan areas. The study also looked at indicators such as educational attainment, median and per-capita income, homicide rates, and life expectancy among the regions, to understand where Chicago placed.

The study’s mission was to find out how segregation affected Chicagoans, said Kendra Freeman, a manager with the MPC.

“In some ways, [Chicago has] reduced levels of racial and economic segregation, but at the pace we’re going, it would take until 2070 to get to [the national] median level [of segregation],” Freeman said. “We don’t have time to waste. We’re losing income, and we’ve lost potential [as well as] lives.”

Out of the cities studied, Chicago has the fifth highest combined racial and economic segregation and the tenth highest African- American-white segregation.

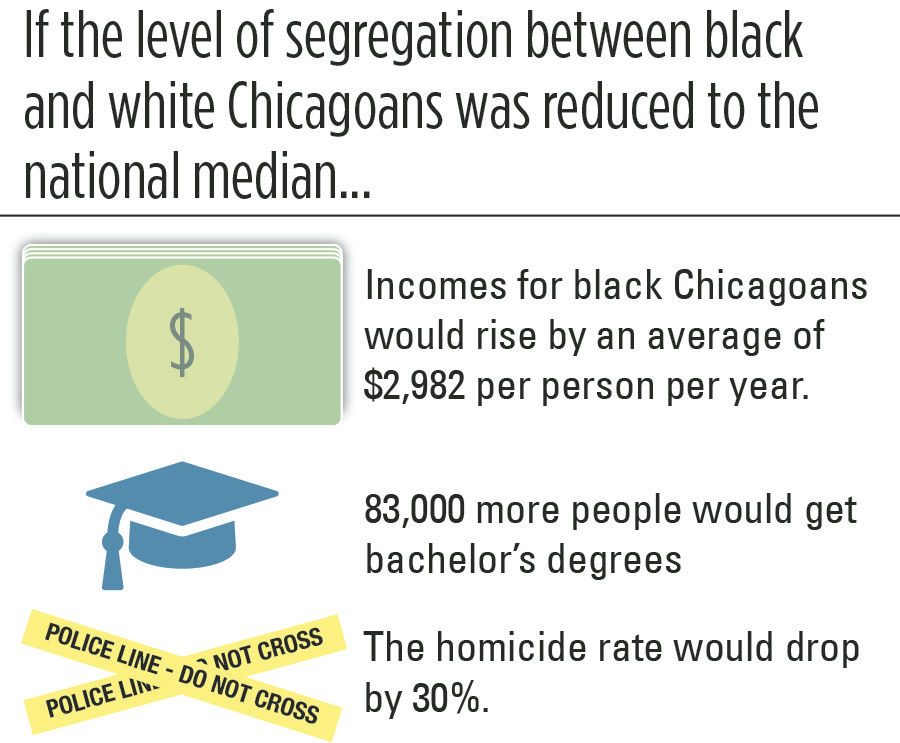

According to the study, if levels of economic segregation between African-American and white Chicago residents were lowered to match the national median, the city’s gross domestic product would rise by approximately $8 billion—250 percent more than the region’s average annual growth. Because of an educational gap in Chicago—a researched correlation found between lower levels of segregation and a higher percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree—the region is losing out on approximately $90 billion in total lifetime earnings of residents.

“When you have a segregated city, you really have two cities, so you have two of everything,” said Stephanie Schmitz Bechteler, vice president and executive director of the Research and Policy Center at the Chicago Urban League, an advocacy group for African-American progression.“[The] history of segregation that we’ve experienced in the city has just continued to lead to dual worlds.”

Schmitz Bechteler said people living in segregated communities tend to be less invested in the community because of the adversity they face, such as job loss because of the withered industrial base on the South and West sides of the city.

Money and opportunities are also lost, causing schools and families to have less money available to offset school funding gaps or pay for better housing, she added.

“It’s hard for the communities to get ahead when you lose a big swathe of your industry and the way people make money and are able to live and work [without] pour[ing] money, resources and efforts back into building up that infrastructure,” she said.

Chicago’s segregation dates back centuries to the city’s origin, said Dick Simpson, a political science professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and former 44th Ward alderman. Segregation was cemented during the Civil War period as the African-American community grew on the South Side, and it has been present ever since, Simpson added.

Chicago’s struggle with integration is related to the city’s political machine, particularly from the era of former Mayor Richard J. Daley, he said. During this time, African-Americans tended to have the authority to have their own aldermen, congressmen and some representation in levels of government. Daley, however, made the African-American community “more second class” because he typically sided with the whites, Simpson said.

According to Freeman, the MPC plans to release a report in early 2018 partnering with neighborhood and community-level leaders, advisers and academic partners to use the data to lessen the level of economic and racial segregation. The report will look into different policy areas such as housing, economic development, public health, safety and education to focus on solutions, she said.

Simpson said Mayor Rahm Emanuel seems to be willing to help with some aspects of Chicago’s segregation but is not willing to confront it “head-on.”

The mayor’s press office was not available for comment as of press time.

“There are different policies that need to be followed, and it’s a matter of having the political will to do them,” Simpson said.

Schmitz Bechteler emphasized persistence is needed for a solution.

“Unless we purposefully work to undo the legacy of segregation, we’re going to have these same stories over and over again,” she said.