‘Chicago History Cop’ making headway in Grimes sisters’ murder case

October 25, 2019

The Chicago Machine, false confessions and even the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll—Elvis Presley—all played major roles in the real-life Chicago drama of the ‘50s: the unsolved murder of the Grimes sisters.

When retired detective with the West Chicago Police Department Ray Johnson began researching the Grimes’ case for a chapter in his 2011 history book, “Chicago’s Haunt Detective,” he became infatuated. Johnson, known as the “Chicago History Cop,” began digging deeper and made several discoveries, all of which have advanced the investigation of this case after more than 60 years of stagnancy.

“The more I looked into it, the more stuff I found out,” Johnson said. “Then, of course, the cop in me took over.”

At a presentation in the West Lawn branch of the Chicago Public Library, 4020 W. 63rd St., Oct. 21, Johnson set the scene of the Grimes murders for a crowd of about 50 people.

On Dec. 28, 1956, Barbara, 15, and Patricia, 13, presumably took the bus from their McKinley Park home to Brighton Park to see the 1956 Elvis Presley movie “Love Me Tender” at the now-closed Brighton Theatre, 4223 S. Archer Ave. But after they left the house that night, their family never saw them alive again.

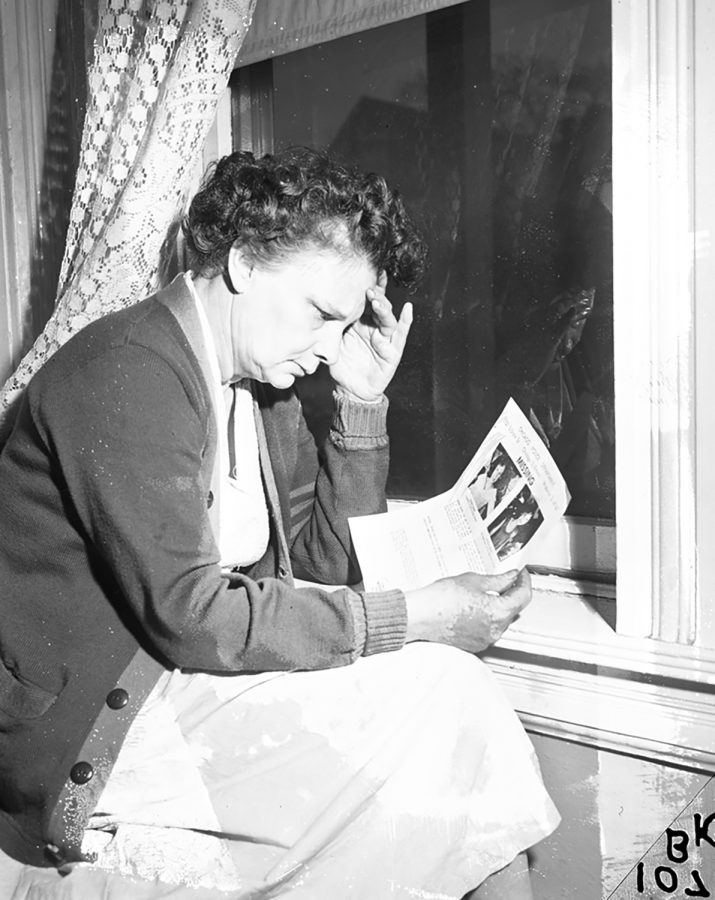

Initially, police thought the sisters had simply run away, perhaps to Memphis to be close to Elvis himself. However, the girls’ mother, Loretta Grimes, knew the girls too well for that to be true.

Nearly everyone in Chicago looked for the sisters. The search is still the largest manhunt in the city’s history in terms of hours spent. The case quickly began to garner national attention, especially when Elvis heard about the girls and how they turned up missing after seeing his movie. He subsequently pleaded for them to come home on national radio.

Finally, the search ended on Jan. 22, 1957. Leonard Prescott was driving east on German Church Road in Burr Ridge when he thought he saw two mannequins on the other side of the guard rail. He went back to his house to get his wife, then came back and discovered the mannequins were actually the bodies of Barbara and Patricia Grimes.

The police scrambled to confirm a suspect, and they landed on Bennie Bedwell, a part-time dishwasher. The cops rushed Bedwell to a motel, kept him there for three days and by the end of it had coerced him into signing a confession, Johnson said.

However, autopsy reports contradicted the falsified confession. The only cause of death that could be determined was “secondary shock due to exposure to cold temperatures.” Consequently, Bedwell was cleared, and the Grimes case went cold.

A former neighbor of the Grimes family, Melanie Forgala, brought pictures of the Grimes sisters’ brother—whom she briefly went to school with—to Johnson’s presentation.

As a former police officer, it is tough for Johnson to break from his stoic objectivity, but when a member of the audience asked him what he thinks happened to the Grimes sisters, he said he suspects it was “confessed child killer” Charles Melquist.

One reason Johnson suspects Melquist is due to a pair of suspicious phone calls Loretta Grimes received in 1957 and 1959.

In 1957, Grimes got a call, and the unknown caller said he was the one who undressed the girls, Johnson said. Then, nearly 18 months later, on the same night that a newspaper reported the discovery of Bonnie Leigh Scott’s body, she received another call from someone with a similar voice. This time, the caller said he “got away with another one.” He also said the police would not be able to pin this one on Bedwell or Barry Cook, two suspects in the case.

Melquist, who is deceased, was never charged with killing the Grimes sisters. He did, however, confess to killing Bonnie Leigh Scott in Addison, Illinois, in 1958. Melquist only served eight years of his 99-year sentence for murdering Scott. Johnson said Melquist had a connection to the lead investigator in the Grimes case, Sheldon Teller, and through Teller also had ties to the mob. His connections within the “Chicago Machine” could have been the reason for Melquist not being charged in the Grimes case, Johnson said.

He hopes a documentary he has in the works will boost public interest and eventually lead to more people contributing resources to solving the case.

“That’s the whole idea, is to keep it in the public eye so people keep looking at it,” Johnson said. “Somebody knows something and has heard something.”