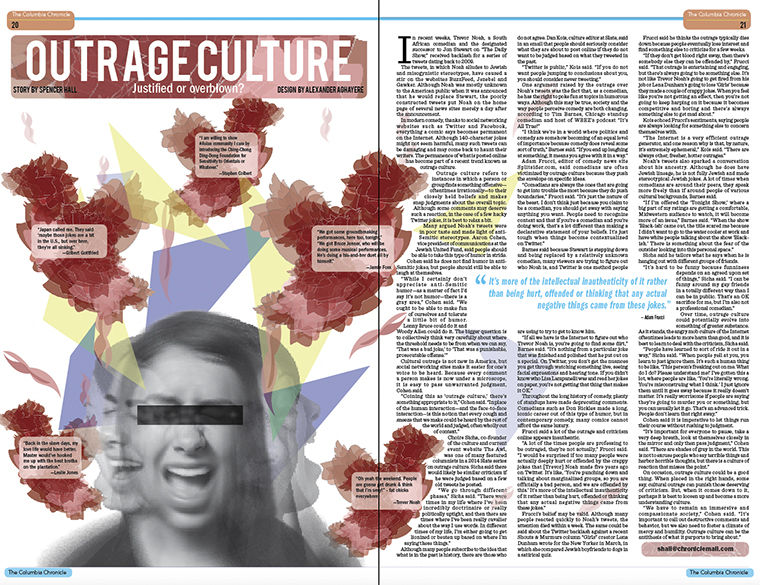

Outrage Culture: Justified or overblown?

Outrage Culture: Justified or overblown?

April 27, 2015

In recent weeks, Trevor Noah, a South African comedian and the designated successor to Jon Stewart on “The Daily Show,” received backlash for a series of tweets dating back to 2009.

The tweets, in which Noah alludes to Jewish and misogynistic stereotypes, have caused a stir on the websites BuzzFeed, Jezebel and Gawker. Although Noah was mostly unknown to the American public when it was announced that he would replace Stewart, the poorly constructed tweets put Noah on the home page of several news sites merely a day after the announcement.

In modern comedy, thanks to social networking websites such as Twitter and Facebook, everything a comic says becomes permanent on the Internet. Although 140-character jokes might not seem harmful, many such tweets can be damaging and may come back to haunt their writers. The permanence of what is posted online has become part of a recent trend known as outrage culture.

Outrage culture refers to instances in which a person or group finds something offensive—oftentimes irrationally—to their closely held beliefs and makes snap judgments about the overall topic. Although some comments may deserve such a reaction, in the case of a few hacky Twitter jokes, it is best to relax a bit.

Many argued Noah’s tweets were in poor taste and made light of anti-Semitic stereotypes. Aaron Cohen, vice president of communications at the Jewish United Fund, said people should be able to take this type of humor in stride. Cohen said he does not find humor in anti-Semitic jokes, but people should still be able to laugh at themselves.

“While I certainly don’t appreciate anti-Semitic humor—as a matter of fact I’d say it’s not humor—there is a gray area,” Cohen said. “We ought to be able to make fun of ourselves and tolerate a little bit of humor. Lenny Bruce could do it and Woody Allen could do it. The bigger question is to collectively think very carefully about where the threshold needs to be from when we can say, ‘That was a bad joke,’ to ‘That was a punishable, prosecutable offense.’”

Cultural outrage is not new in America, but social networking sites make it easier for one’s voice to be heard. Because every comment a person makes is now under a microscope, it is easy to pass unwarranted judgment, Cohen said.

“Coining this as ‘outrage culture,’ there’s something appropriate to it,” Cohen said. “In place of the human interaction—and the face-to-face interaction—is this notion that every cough and sneeze that we make could be heard by the rest of the world and judged, often wholly out of context.”

Choire Sicha, co-founder of the culture and current event website The Awl, was one of many featured columnists in a 2014 Slate series on outrage culture. Sicha said there would likely be similar criticism if he were judged based on a few old tweets he posted.

“We go through different phases,” Sicha said. “There were times in my life where I’ve been incredibly doctrinaire or really politically uptight, and then there are times where I’ve been really cavalier about the way I use words. In different times of my life, I’m either going to get lionized or beaten up based on where I’m saying these things.”

Although many people subscribe to the idea that what is in the past is history, there are those who do not agree. Dan Kois, culture editor at Slate, said in an email that people should seriously consider what they are about to post online if they do not want to be judged based on what they tweeted in the past.

“Twitter is public,” Kois said. “If you do not want people jumping to conclusions about you, you should consider never tweeting.”

One argument raised by the outrage over Noah’s tweets was the fact that, as a comedian, he has the right to poke fun at topics in humorous ways. Although this may be true, society and the way people perceive comedy are both changing, according to Tim Barnes, Chicago standup comedian and host of WBEZ’s podcast “It’s All True!”

“I think we’re in a world where politics and comedy are somehow becoming of an equal level of importance because comedy does reveal some sort of truth,” Barnes said. “If you end up laughing at something, it means you agree with it in a way.”

Adam Frucci, editor of comedy news site Splitsider.com, said comedians are often victimized by outrage culture because they push the envelope on specific ideas.

“Comedians are always the ones that are going to get into trouble the most because they do push boundaries,” Frucci said. “It’s just the nature of the beast. I don’t think just because you claim to be a comedian, you should get away with saying anything you want. People need to recognize context and that if you’re a comedian and you’re doing work, that’s a lot different than making a declarative statement of your beliefs. It’s just tough when things become contextualized on Twitter.”

Barnes said because Stewart is stepping down and being replaced by a relatively unknown comedian, many viewers are trying to figure out who Noah is, and Twitter is one method people are using to try to get to know him.

“If all we have is the Internet to figure out who Trevor Noah is, you’re going to find some dirt,” Barnes said. “It’s nothing from a particular joke that was finished and polished that he put out on a special. On Twitter, you don’t get the nuances you get through watching something live, seeing facial expressions and hearing tone. If you didn’t know who Lisa Lampanelli was and read her jokes on paper, you’re not getting that thing that makes it OK.”

Throughout the long history of comedy, plenty of standups have made deprecating comments. Comedians such as Don Rickles made a long, iconic career out of this type of humor, but in contemporary comedy, many comics cannot afford the same luxury.

Frucci said a lot of the outrage and criticism online appears inauthentic.

“A lot of the times people are professing to be outraged, they’re not actually,” Frucci said. “I would be surprised if too many people were actually deeply hurt or offended by the crappy jokes that [Trevor] Noah made five years ago on Twitter. It’s like, ‘You’re punching down and talking about marginalized groups, so you are officially a bad person, and we are offended by this.’ It’s more of the intellectual inauthenticity of it rather than being hurt, offended or thinking that any actual negative things came from these jokes.”

Frucci’s belief may be valid. Although many people reacted quickly to Noah’s tweets, the attention died within a week. The same could be said about the Twitter backlash against a recent Shouts & Murmurs column “Girls” creator Lena Dunham wrote for the New Yorker in March, in which she compared Jewish boyfriends to dogs in a satirical quiz.

Frucci said he thinks the outrage typically dies down because people eventually lose interest and find something else to criticize for a few weeks.

“If they don’t get blood right away, then there’s somebody else they can be offended by,” Frucci said. “That outrage is entertaining and engaging, but there’s always going to be something else. It’s not like Trevor Noah’s going to get fired from his job or Lena Dunham’s going to lose ‘Girls’ because they made a couple of crappy jokes. When you feel like you’re not getting an effect, then you’re not going to keep harping on it because it becomes competitive and boring and there’s always something else to get mad about.”

Kois echoed Frucci’s sentiments, saying people are always looking for something else to concern themselves with.

“The Internet is a very efficient outrage generator, and one reason why is that, by nature, it’s extremely ephemeral,” Kois said. “There are always other, fresher, hotter outrages.”

Noah’s tweets also sparked a conversation about his ancestry. Although he does have Jewish lineage, he is not fully Jewish and made stereotypical Jewish jokes. A lot of times when comedians are around their peers, they speak more freely than if around people of various cultural backgrounds, Barnes said.

“If I’m offered the ‘Tonight Show,’ where a big part of my ratings are getting a comfortable, Midwestern audience to watch, it will become more of an issue,” Barnes said. “When the show ‘Black-ish’ came out, the title scared me because I didn’t want to go to the water cooler at work and have white people talking about the show ‘Black-ish.’ There is something about the fear of the outsider looking into this personal space.”

Sicha said he tailors what he says when he is hanging out with different groups of friends.

“It’s hard to be funny because funniness depends on an agreed upon set of things,” Sicha said. “I can be funny around my gay friends in a totally different way than I can be in public. That’s an OK sacrifice for me, but I’m also not a professional comedian.”

Over time, outrage culture could potentially evolve into something of greater substance. As it stands, the angry mob culture of the Internet oftentimes leads to more harm than good, and it is best to learn to deal with the criticism, Sicha said.

“People have learned to sort of ride it out in a way,” Sicha said. “When people yell at you, you learn to just ignore them. It’s such a human thing to be like, ‘This person’s freaking out on me. What do I do? Please understand me!’ I’ve gotten this a lot, where people are like, ‘You’re literally wrong. You’re misconstruing what I think.’ I just ignore them until it goes away because it really doesn’t matter. It’s really worrisome if people are saying they’re going to murder you or something, but you can usually let it go. That’s an advanced trick. People don’t learn that right away.”

Cohen said it is imperative to let things run their course without rushing to judgment.

“It’s important for everyone to pause, take a very deep breath, look at themselves closely in the mirror and only then pass judgment,” Cohen said. “There are shades of gray in the world. This is not to excuse people who say terrible things and harbor horrible thoughts, but there is a culture of reaction that misses the point.”

On occasion, outrage culture could be a good thing. When placed in the right hands, some say, cultural outrage can punish those deserving of criticism. But, when it comes down to it, perhaps it is best to loosen up and become a more understanding culture.

“We have to remain an immersive and compassionate society,” Cohen said. “It’s important to call out destructive comments and behavior, but we also need to foster a climate of mercy and humility. Outrage culture can be the antithesis of what it purports to bring about.”