Chicago looks to education to battle opioid addiction

Chicago looks to education to battle opioid addiction

November 27, 2017

With the help of additional funding, Chicago will focus on education to counter the city’s growing opioid addiction problem.

As part of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s 2018 budget proposal, the city will invest an additional $500,000—bringing the total to $2.95 million—in opioid prevention and education. The proposed funding will support another 500 participants in recovery homes and Medication Assisted Treatment—a combination of medicine and counseling to treat and prevent addiction.

Chicago also launched the website OvercomeOpioids.com in the last week of October, as a resource that provides information on how to prevent, recover and understand opioid addictions.

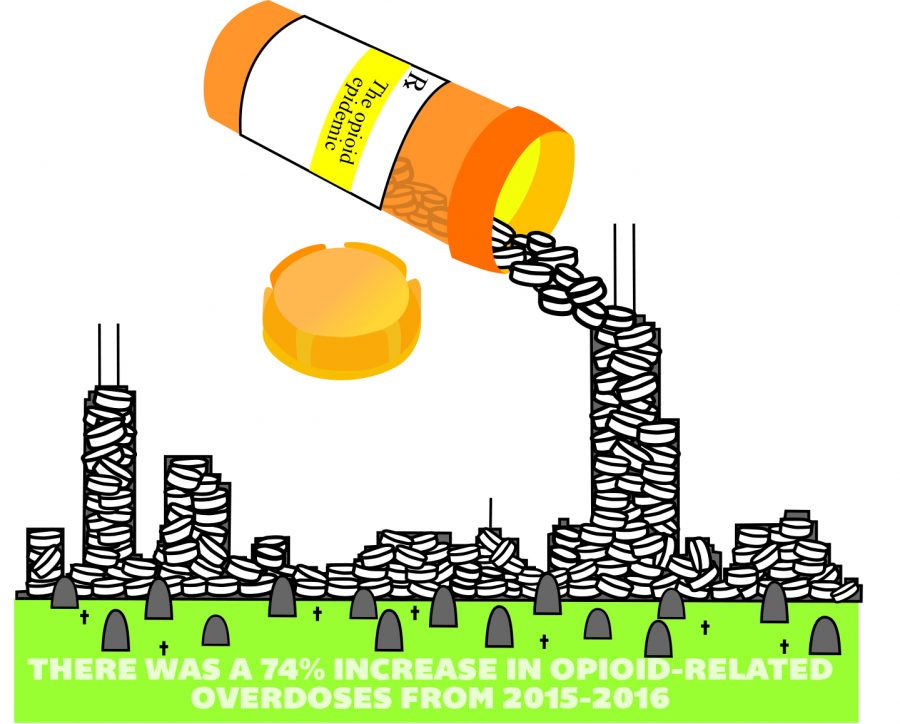

Chicago’s fatal opioid-related overdoses rose to 741 in 2016, which is 315 more than 2015, according to an October Chicago Department of Public Health Epidemiology report.

“Opioid addiction is a disease. It’s not a matter of moral failing, strength of character or willpower,” said John Benedetto, doctor at Brightside Clinic, a treatment center in Northbrook, Illinois. “Overuse of opioids creates chemical brain damage that needs to be [treated] by a medicine until the brain can heal.”

Opioids are commonly used as painkillers. People can become addicted to opioids when they are over-prescribed, which creates more receptors in the brain and can cause people to make impulsive decisions, such as abusing the drug, according to Benedetto.

A September 2017 report by the Center for Disease Control discovered that doctors in the U.S. are over-prescribing opioids, contributing to the causes of addiction.

Patients will eventually run out of their prescriptions, Benedetto said, which can lead to complications such as withdrawal. This sensation can cause an addict to turn to other drugs like heroin, a cheaper drug that may produce a similar high.

At Brightside Clinic, doctors will make sure to develop relationships with patients in order to prevent further problems. Sometimes doctors spend hours with patients, he added.

“Addiction is not [a] crime. [This is] a healthcare issue rather than a criminal justice issue,” said Patty McCarthy Metcalf, executive director at Faces and Voices of Recovery, an addiction recovery organizing based out of Washington, D.C.

From 2002–2015, opioid-related deaths nationwide have been steadily increasing, and heroin-related deaths have almost tripled in four years, from 2011–2015, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The best way to fight opioid addiction is education and understanding rather than the criminal justice system, according to experts. By removing the stigma surrounding addiction, people will be more willing to talk about their experiences and seek help, according to experts.

“Public awareness is a huge step to eliminating the stigma of addiction in communities,” McCarthy Metcalf said. “Addiction to opioids is preventable [and] treatable, and there are millions of Americans in long-term recovery.”

The new, navigable website is a progressive step with its hot line, education on what opioids are and prevention information, which can help reduce addiction, according to Leonard Jason, a psychology professor at DePaul University.

“We have a major catastrophe occurring,” Jason said. “We have to be a proponent of best practices.”