North Side cultural center unites Rohingya refugees together

November 28, 2017

Nasir Zakaria is one of hundreds of Rohingya, a stateless Indo-Aryan people from the Rakhine State, Myanmar, who found refuge in Chicago’s North Side. After immigrating to the U.S. from Myanmar in 2013 and settling in Rogers Park, Zakaria said he could not sit idly while his people suffered from horrendous persecution.

Zakaria founded the Rohingya Cultural Center, 2740 W. Devon Ave., in April 2016 with assistance from the Zakat Foundation, a Muslim organization that provides an annual grant to pay rent, utilities and Zakaria’s salary.

“The Rohingya [had] no place to learn English, no place to sit down together, so we made a place for everyone to meet here,” Zakaria said.

The Rohingya Cultural Center has a three-fold mission: to provide Rohingya refugees support and education, create a haven where the Rohingya can celebrate and preserve their language and culture, and voice opposition to the genocide against Rohingya by the Myanmar government.

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority in Myanmar whom the United Nations calls the most persecuted minority in the world. In 1982, the Myanmar government stripped the Rohingya of their citizenship, which led to Rohingya homes and lands being seized, schools and businesses closed and people beaten, imprisoned and killed.

Zakaria said he grew up in a world where it was like “living in a dark area.”

There are only about 2 million Rohingya in the world, and most are refugees in neighboring countries, such as Bangladesh, Thailand and Malaysia, according to Zakaria.

“We love peace in our country, ” Zakaria said. “The government try to say [we are] bad people [because we are] Muslim. They [discriminate] not only Muslim but any [non-Buddhist] religion. They want to keep [Myanmar] a Buddhist country.”

The Rohingya Cultural Center is the perfect place for Rohingya to settle because Rogers Park has become a Chicago hub for other Asian groups, said Laura Toffenetti, a volunteer and board member for the center.

Rohingya have an unwritten language, and most are illiterate and have never attended school, Toffenetti said. The Rohingya are given permanent status in the U.S. and are allowed to apply for citizenship after five years, but they have to write and speak English, Toffenetti added.

By order from the Trump administration, the U.S. government will only accept 50,000 international refugees into the country in 2017, which is not enough, Toffenetti said.

“The challenges [the Rohingya] community faces are that they only started arriving [in Chicago] in 2012, so there’s not that established group to get them jobs and housing,” Toffenetti said. “The languages they speak are rare, and there aren’t a lot of translators available.”

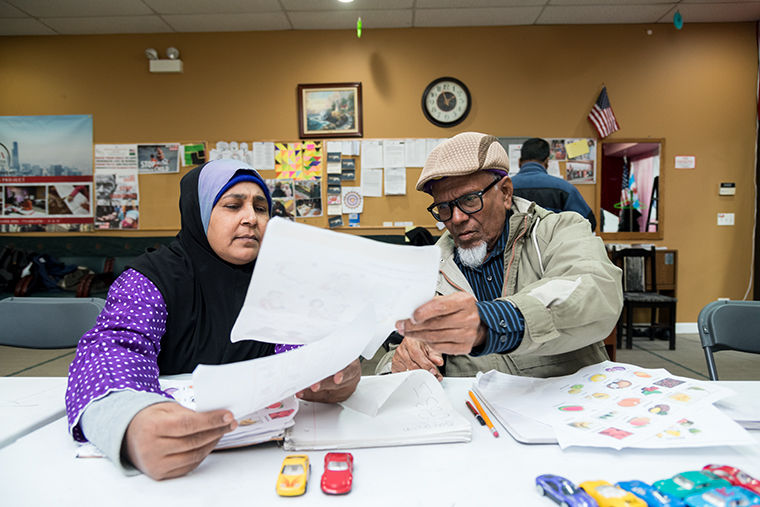

As a volunteer, Toffenetti helps with casework and English as Second Language classes for the center, but she is not a translator. A majority of Rohingya receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits and Medicare in the U.S., Toffenetti said, but because they cannot read the letters and notices that come in the mail, many of them lose their benefits.

Sana Sultan, a Rohingya who was born and raised in Dubai and came to the U.S. in 2016, is the center’s translator and caseworker. She said she assists fellow Rohingya make doctor appointments, enroll in school and fill out forms for food vouchers. The cultural center feels like home, Sultan said, because she gets to speak her language.

“[The center] is doing good now,” Sultan said. “People are happy to come here. They have a place nearby they can find help.”

Despite finding a home in Chicago, Toffenetti said the Rohingya are still burdened by the overbearing stress about their family members who are still in Myanmar.

“My parents and family are in [Myanmar], I am worried because I will call tonight, and they are OK, but how about tomorrow? Are they alive?” Zakaria said. “This is always a cry from my heart.”

Update 11/28/17 at 2:30 p.m.: A previous version of this story incorrectly said the U.S. government accepts 54,000 Rohingya refugees. According to the Pew Research Center, the U.S. government will accept 50,000 total international refugees in 2017, a change made by the Trump administration. The Chronicle regrets these errors.