House bill aims to gouge the gougers

House bill aims to gouge the gougers

March 4, 2018

To crack down on price gouging and provide millions of Illinoisans better access to life-saving medical prescriptions, a proposed Illinois House bill would impose punishments on companies that unjustly raise their prices.

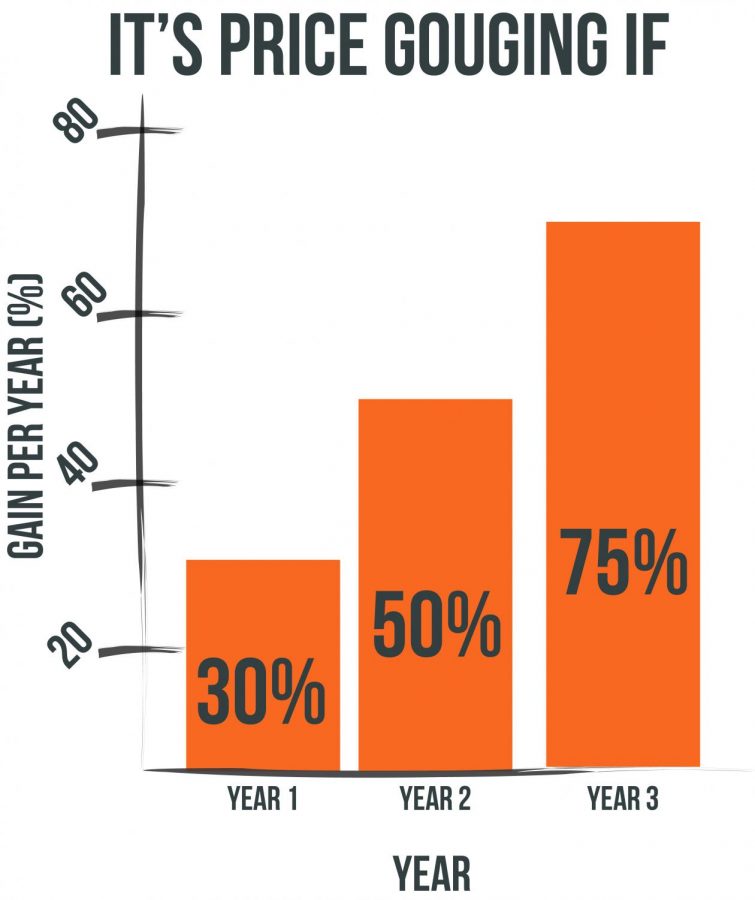

The Illinois Generic Drug Pricing Fairness Act defines price gouging as a 30 percent or more price increase within one year, 50 percent or more within three years or 75 percent or more within five years. However, not every increase in price would be considered price gouging.

Companies have a limited time to prove the increase in cost was justified before being taken to court, said state Rep. Will Guzzardi, D-Chicago, who introduced House Bill 4900 Feb. 14.

“There is not always a lot of competition out there,” Guzzardi said. “If one company raises prices, it’s not always the case where you can get it somewhere else, even with generic drugs.”

The bill would also grant Illinois’ attorney general authority to punish pharmaceutical companies who price gouge.

The penalties include fines up to $10,000 per violation, restitution to patients who paid the increased prices and the ability to make them sell the medication at the pre-hike price, according to Guzzardi.

The bill covers three categories: generic, off-patent drugs, which have expired patents leading to approval of a generic drug, and delivery devices such as EpiPens or inhalers, according to Guzzardi.

The bill passed the Human Services Committee, 7–5, Feb. 28 and is waiting to be called for a full House vote, according to state legislative records.

For some families, unexpected and unwarranted increases to medication prices could cause a variety of serious problems, said Ally Dering-Anderson, clinical associate professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practices at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

If a drug costs 9 cents one day, then $200 the next, there is no way families can adapt or budget for that. That can force families to make difficult decisions on whether they fill their prescription or pay their bills, she said.

“Can price gouging [actually] kill people? Not directly,” Dering-Anderson said. “But you don’t have to go far to find the connection.”

The bill would provide benefits to more than just patients who use prescribed medication, Guzzardi said. It could help the state balance the budget because companies who unjustly raise prices on patients increase the state’s contribution to Medicare.

Price gouging is not a new problem, and the U.S. has seen some pretty extreme cases over the years, said Ana Santos Rutschman, Jaharis faculty fellow in Health Law and Intellectual Property at DePaul University. Bills like this are overdue and showcase even less egregious price gouging cases, she added.

Both Rutschman and Dering-Anderson applaud the bill’s ability to shine a spotlight on companies who are unethically raising prices. But they are afraid the bill lacks the teeth to deter and punish large pharmaceutical companies and prevent future instances of price gouging.

However, Guzzardi is confident the bill has the power to deter companies from price gouging.

“We are not going to cater to the objections of [the pharmaceutical] industry that wants to continue gouging consumers without any regulations at all,” Guzzardi said. “We believe the Illinoisans who rely on these prescription medications are more important than drug companies who are trying to pad their pockets.”