Illegal inking: Scratching the surface of illegal tattooing

Scratching the surface of illicit tattooing

January 27, 2014

“She told me to do whatever I felt like I wanted to do, which is a really awesome gift to your tattooist.”

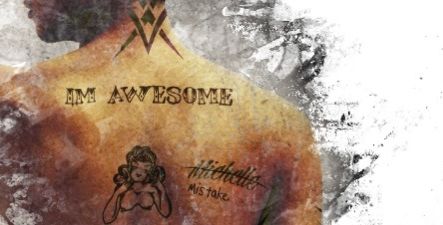

Leaning over a client with the tattoo gun buzzing in his hand, Madsen Minax prepared to freehand a piece of body art across the back of a girl he hardly knew. But instead of sitting among the bright lights and scoured tabletops of a tattoo parlor, the two sat in Minax’s ordinary Rogers Park apartment.

Minax was an unlicensed tattoo artist, which is illegal in Illinois and most states. He uses professional equipment that he purchased online through a tattoo supply company, but he never took the necessary courses in sanitation to obtain certification. Learning the craft was difficult for Minax—who relocated to Houston a year and a half ago—because there are few resources available for amateurs, he said. So to hone his skills, Minax practiced on his bandmate Simon and other friends who didn’t want to pay a premium for their body art.

“I bought a bunch of s–t online, really crappy stuff, and started practicing,” Minax said. “One of the things about [tattooing] is there’s really not a great way to learn besides just doing it.”

Minax said the practice of illegal tattooing is becoming increasingly appealing to consumers because tattoos done by non-certified artists are less expensive than professional body art. Illegal tattooists have been able to meet this demand as high-end equipment has become readily available through websites such as Ebay and Craigslist, he said.

Most of Minax’s clients had designs in mind, but occasionally he said he would sketch directly on their skin before tattooing. He never took a blood-borne pathogen course but said cleanliness was not a problem for him. He wasn’t worried about sanitation because most tools are single-use and disposable, and he always washed his hands and the area that would be tattooed. Most of the people he tattooed were friends who trusted him and sought his services to save cash, and Minax was happy to oblige.

Increasingly, people of all ages are flooding into tattoo parlors—nearly 40 percent of millennials are inked, according to a February 2010 Pew Research Center poll. However, high prices are a deterrent, leading some to turn to amateur tattoo artists, sometimes known as “scratchers,” to avoid paying anywhere from $60 for small tattoos to thousands of dollars for large ones, according to Mike Martin, president of the Alliance of Professional Tattooists. Some are even willing to poke themselves with needles and ink repetitively in a do-it-yourself method known as a “stick-and-poke.”

Many get illegal tattoos when they attend tattoo parties, said Ricardo Avila, an artist at Native Soul Tattoo, 1712 S. Ashland Ave. In Illinois it is illegal to tattoo someone anywhere except a state-licensed tattoo shop, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health’s administrative code for body art, even if the artist is properly licensed. But tattoo parties are becoming increasingly popular among licensed artists, who travel to customers’ homes to ink for considerably less than they would ask in licensed parlors, he said.

Bridget Traverso, a sophomore interactive arts & media major, got her first tattoo at age 17 in a family friend’s dining room from a licensed artist who was between studios.

Traverso said while she doesn’t regret saving money on what could have been a very expensive tattoo—she paid $70 for the custom design of a girl pulling the moon like a balloon—although it is beginning to fade and is not of the same caliber as a tattoo she got in a professional Chicago parlor.

“It’s been needing a touch-up for a year or so,” Traverso said. “I’d rather get one from a shop. It’s more professional and generally the tattooist takes it a little bit more seriously when they’re at their shop.”

While amateur tattoos may be more cost-effective, professional artists are quick to condemn them.

“We try to tell people here that good tattoos aren’t cheap and cheap tattoos aren’t good,” Avila said. “Most people that learn at home don’t really have an education on keeping things sterile.”

Avila, who has been a licensed artist at Native Soul since 2011, said his customers occasionally complain about the quality of their illegal tattoos. Although the artistic value and quality may be lacking, he said, the main concern surrounding illegal tattoos is sanitation. Before receiving their certifications, artists are required to apprentice in licensed shops and complete a series of sanitation courses, which includes instruction about blood-borne pathogens that can be transferred through needles and poorly sanitized tattoo equipment, according to the IDPH’s body art code.

Hepatitis C, a viral infection of the liver, is another common consequence of receiving tattoos in unlicensed settings such as homes. It was found to be nonexistent in licensed settings though, according to a 2012 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C is usually transmitted by sexual or blood contact and can lead to liver cancer, according to the National Institutes of Health. Sometimes infectious pathogens can even be found in improperly mixed tattoo ink. In 2012, infected tattoo ink from a single artist in a parlor led to nontuberculosis mycobacteria infections in 14 people in Monroe County, N.Y., according to a Food and Drug Administration report. NTM infections are typically not deadly but can cause painful skin rashes and scarring, according to the NIH.

Unless tattooists pass an exhaustive licensing exam, they will not be approved for practice. The Illinois codes for opening a tattoo parlor clearly outline rigorous sanitation standards along with the required expertise in anatomy, hygiene and infectious diseases. Tattoo artists must wear medical-grade gloves that touch only the equipment and the person, dispose of all single-use needles and inks immediately after the procedure, and decline to tattoo an area with any infection or irritation. Additionally, they are forbidden to work if they have any illness or infection that could compromise the sterility of the equipment or tattoo area.

Once the artist obtains certification, he or she must also go through the city’s licensing process to open a parlor. Mayor Rahm Emanuel has loosened the requirements for business license procedures in hopes of fostering more local businesses, according to David Staudacher, information coordinator for Business Affairs and Consumer Protection, the city’s licensing bureau. However, tattoo parlors must still comply with the state’s extensive hygiene requirements.

Mike Martin, president of the Alliance for Professional Tattooists, said it is important for individuals to research state sanitation requirements for tattoo parlors and properly care for tattoos after they leave the shop. A tattooist of more than 30 years, Martin said most ink-related infections that stem from tattoos done at a licensed shop are the result of poor aftercare rather than the business’s sanitary procedures.

“There is responsibility they have to take for their own safety and their own health,” Martin said. “Once they leave the shop, we don’t know what they’re doing. They could go mud wrestling for all we know.”

The education requirements and threats of consequences are not empty. After 18-year-old Michael Whitlock of Edwardsville, Ill. gave an illegal tattoo to an underage boy who later developed a staph infection, he was convicted of child endangerment, fined and sentenced to prison in 2010, according to the Madison County circuit court documents.

Chicago’s roots in illegal tattooing date back to Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins, a prolific tattoo artist in the mid-20th century, who started his career by tattooing drunks on State Street, according to “Hori Smoku Sailor Jerry: The Life of Norman K. Collins,” a 2008 documentary about his career. Regulations have since been imposed, but one item that falls into a grey area is tattooing anywhere other than a parlor. State regulations strictly forbid tattooing in an area other than a licensed business, but even licensed artists sometimes work away from their parlors for events and promotions.

Annual celebrations are held in honor of Sailor Jerry’s Jan. 14 birthday, and this year tattoo artist Nick Colella led a crew that tattooed 103 people inside Emporium Arcade Bar, 1366 N. Milwaukee Ave. Each year, they tattoo a small bluebird, the insignia of Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum—named in honor of the tattooist—on the number of people equal to Sailor Jerry’s age.

But this year, for the first time, Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum asked the artists to work in Emporium Arcade Bar instead of in a tattoo parlor, which, according to state law, is illegal. Non-parlor tattoos are illegal; the exception is tattoo conventions, which are granted a special use license from the state’s department of health, Martin said.

“It’s really something I’m not too thrilled about, doing stuff outside of the shop other than at conventions,” Colella said. “Everything at my station in a tattoo shop, I know where it is with my eyes closed. Anything outside the shop is more challenging because it’s not a familiar space. I like working in a shop because it’s set up to tattoo all the time.”

However, Colella said the tools he used during the event were single-use, which kept the area sanitary. He said home tattooists may use some sanitation precautions, but they do not have the knowledge or professionalism of certified tattoo artists, making the art poorer and increasing health risks.

Minax disagreed, saying professional tattoo artists treat tattoos like a product to be sold. Body art is an intimate exchange between the artist and the person receiving the tattoo, and tattooing in the comfort of his own home with free reign over art he wanted to create enhanced that experience, he said.

“I know very few tattooists that have a broad philosophical idea about what body modification means and does in the world,” Minax said. “I think that kind of leads back to the closed-mindedness about who’s entitled to do it and who’s not.”