For Iba Varga, learning American Sign Language felt like home.

Growing up hard of hearing with autism and delayed speech, Varga, who is autistic, did not start communicating with spoken works until she was seven. Then, during the COVID-19 pandemic, she stopped speaking again.

That is when she started to learn ASL through an app called Preply. Soon after, she got involved with Deaf Planet Soul, a Chicago-based organization to empower and provide services to Deaf and hard of hearing people.

Varga said joining the community during lockdown was the first time she felt she belonged somewhere.

“I felt home. I felt seen,” Varga said.

Her passion for the language brought Varga to Columbia, where she is now a first-year ASL major.

Established 30 years ago, Columbia’s American Sign Language Department has grown since its inception, although its enrollment dipped since the pandemic.

Peter Cook, ASL Department chair and associate professor, said there were very few programs at the time that offered a four-year focus on interpreter training at the time.

The course “American Sign Language I” was the first sign language class at Columbia and now has six sections. The department’s growth is partly due to the growth of ASL learning in the mainstream, Cook said.

“There are so many more high schools that are offering it now than in the past,” Cook said. “Now they’ve had two or three years of experience in high school, and it’s recognized as a world language. So, they come to me, and we have placement exams.”

While the ASL Department was expanding over the years, the number of ASL majors has dropped since 2020, due to the difficulties of learning sign language virtually.

“COVID occurred just as the college was experiencing an uptick in enrollment and with COVID there was a decrease in college enrollment nationwide,” said Liberal Arts and Sciences Dean Steven Corey.

The pandemic hit ASL majors hard due to the course being a three-dimensional language, Corey said.

Senior ASL-English interpretation major Arriana Lyles’ first time being immersed in Deaf culture was at Columbia.

“It was hard for me when finding a program dealing with ASL-English interpretation since there are not a lot of schools offering near me,” Lyles said.

Lyles was an ASL major during the 2020 lockdown and said it was “hard to adjust.”

“I am a hands-on, in-person learner [and] ASL is a 3D language, you want to make sure you are doing the signs right because if not you might cause confusion when signing with a Deaf person,” Lyles said.

ASL enrollment data shows a total of 123 Deaf Studies and ASL English-Interpretation undergraduate majors in 2018 and 82 in 2022.

“We’re slowly expanding and we’re very hopeful that we can get back to the size we were before COVID,” Cook said. “We’re seeing changes there and we’re evolving.”

Corey suggests that a solution to the drop in ASL majors could be the “strong nation-wide demand for ASL interpreters.”

Lyles hopes that the department will become more diverse in the future. Data from the institutional effectiveness database shows that 94% of ASL English-Interpretation majors in 2018 were white and 88.4% in 2022.

“My hope is that more students from different ethnic backgrounds join in these programs to make this field more diverse. Because it makes me feel good if we, people of color, can impact other students who may feel like the odd ones out from this major,” Lyles said.

Cook said having such a strong media college is a great opportunity to expand with people who are into art with Deaf art history or theater productions.

“I aim to do projects that are related to sign language to a Deaf theater production instead of actors who are speaking, we can have some Deaf actors come work with them,” Cook said.

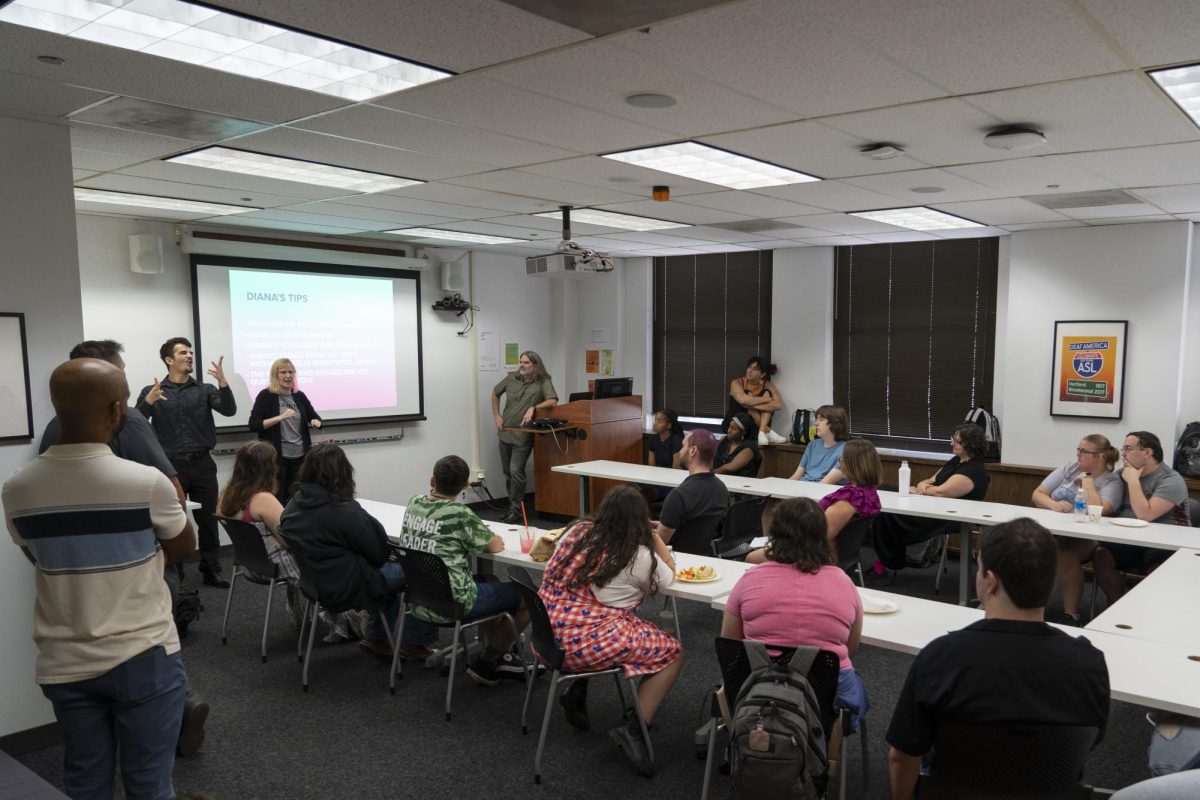

The ASL club is open to hearing students who do not know sign language and members encourage involvement from all students. Cook said he hopes to see more partnerships with other departments.

“I think ‘why don’t we work with the fashion department to come up with something that looks really cool.’ They have special vests that you can wear that give vibrations that are becoming more popular so that Deaf people can feel the vibrations,” Cook said.

Lyles said she is excited to be a part of the department.

“We need to be more open to changing our mindset on what we first thought about ASL, its language and culture, and all the things it endured to become a language as we know it today,” Lyles said.