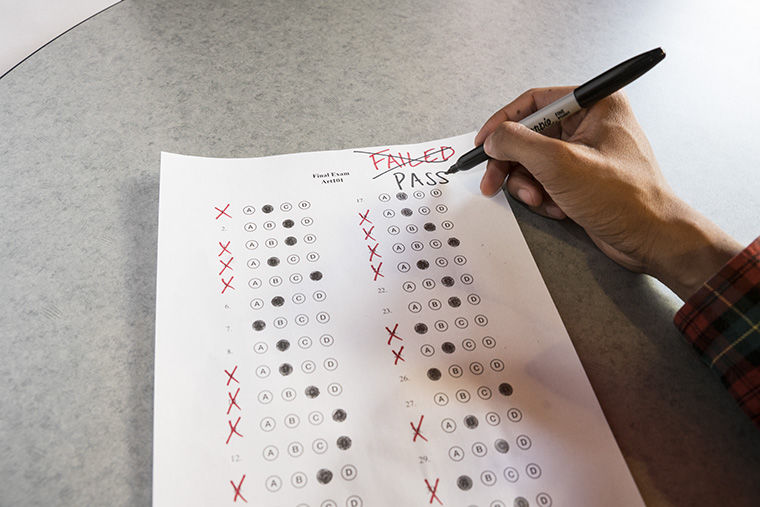

Tipping the scale: Adjuncts accuse administration of demanding ‘unethical’ grade changes

April 10, 2017

Tipping the scale: Adjuncts accuse administration of demanding ‘unethical’ grade changes

After a student missed 10 of the 15 class sessions for a course, adjunct professor in the Creative Writing Department Marcia Brenner gave the student a failing grade. Soon after, she said college administrators asked her to change the grade to a pass.

The college’s faculty manual states that Columbia does not have a collegewide attendance policy, but most departments include in syllabuses that students cannot miss more than three classes before failing or facing an automatic grade decrease.

Brenner’s syllabus stated that students could not miss more than three classes without automatically failing, she said. Apart from nonattendance, she said there were also coursework requirements assigned in the syllabus that the student did not fulfill to receive a passing grade.

She said Creative Writing Department Interim Chair Tony Trigilio told her via email that the student had gone to speak with Senior Vice President and Provost Stan Wearden, who wanted to speak with Trigilio about the grade. Brenner said Trigilio then sent her another email stating Senior Associate Provost Suzanne Blum Malley had presented an alternative method to resolving the grade grievance.

Because of privacy laws protecting student information, Brenner was not able to share copies of the emails with The Chronicle. Trigilio could not be reached for comment as of press time. Brenner said she was then asked to give the student a new grade based solely on the five weeks of work the student turned in, which she refused.

“To do anything else would be a violation of the syllabus and also, I felt, unethical,” Brenner said. “[Trigilio] assured me he completely understood my decision, but he had been told they will find another instructor to read the work and give the student a new, I assume, passing grade.”

According to a March 14 email sent to members of Columbia’s part-time faculty union, Brenner’s situation is just one example of a concerning pattern of faculty members being asked to change failing grades.

In the March 14 email, P-Fac advised faculty to not accept demands for grade changes, citing four separate occasions in which the college demanded grade changes, including one involving the Office of the Provost.

P-Fac president and adjunct professor in the Photography Department Diana Vallera said the union has been investigating for several semesters four situations in which grade changes were made without faculty input or approval—an act she said violates both the college’s policies and faculty’s academic freedom.

The Chronicle requested Vallera ask other adjuncts with grade change complaints if they would be interviewed, but she did not respond as of press time.

“In the cases that we are most alarmed about, we’re seeing a grade that’s just changed by someone higher up and the faculty member may not even be aware of the grade change,” Vallera said.

According to the college’s academic policy, only a course instructor can change a student’s grade. A student must file a grade change request by the end of the semester in which the grade was given, and the department chair and school dean must then approve the changed grade.

The policy also states that every attempt should be made to resolve the grievance through discussions between the student and instructor or among the student, instructor and the department chair before a grade change is made. Grading and evaluation policies outlined in the course syllabus form the basis for grade resolutions, the policy also stated.

Vallera pointed out the college’s policies are vague, with nothing established for situations in which the college administration does not follow the policy.

“I am concerned that if this continues, it’s just going to affect the quality of education, the morale and the value of the Columbia degree,” Vallera said. “The faculty member will always feel the college is just going to override it and allow students to pass, and I don’t think that serves anyone’s best interest.”

Faculty members were advised in the email to not accept demands for grade changes, but to instead inform P-Fac immediately, which will then file a complaint with the college. They were also advised to attend any meetings over grade changes with a P-Fac representative, according the email.

After refusing to change the student’s grade, Brenner said she wrote a letter outlining her concerns to Wearden and Blum Malley, and also sent it to Vallera and other faculty members. According to

Brenner, she did not get a response from any of them. Because of privacy concerns, Brenner was unable to provide a copy of the letter to The Chronicle.

In an April 7 email to the Chronicle, college spokeswoman Cara Birch said she could not confirm or deny whether the provost received the letter because of the The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, which protects the privacy of education records.

College spokeswoman Anjali Julka declined interviews on behalf of Wearden and Steven Corey, the dean overseeing the Creative Writing Department, but sent The Chronicle a statement April 6 outlining Columbia’s support for academic freedom, which, according to the statement, is not affected by asking for grade changes.

“Columbia also has a policy in place to protect a student’s right to appeal a grade,” the statement said. “Grade changes—resulting from review processes required under the college’s grade grievance policies—do not constitute a violation of academic freedom.

If P-Fac’s leadership is accusing the provost or the college of violating academic freedom because a student’s grade was changed, then that complaint should be discussed directly with the college. It is irresponsible for anyone to publicly discuss a student’s grade grievance, as that issue falls strictly under the [FERPA].”

Cary Nelson, a jubilee professor of liberal arts and sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who served as the national president of the American Association of University Professors from 2006–2012 and has written books on academic freedom, said it is unacceptable for an administrator to change a student’s grade, and the responsibility should be left to the instructor of the course.

“If we don’t assume faculty are responsible [for] student grading, the entire system of higher education breaks and we don’t have any faculty autonomy,” Nelson said.

Vallera said she has filed several information requests through the college during the union’s investigation of all instances involving grade changes, including Brenner’s, but has also not received a response.

However, in a separate April 7 email, Birch said she can confirm the college always receives and responds to all information requests.

Brenner said she could not speculate why the Provost’s Office got involved with her student’s grade grievance. One possibility could be an attempt to save student retention rates, Vallera said.

“What’s the interest in the college to pass a student that the faculty feels strongly has not fulfilled the requirements of the course?” Vallera said. “It comes to mind that it’s trying to get those retention rates up and that just can’t happen. We have to always be committing to making sure they fulfill the requirement of the course.”

Nelson added that these issues with grade grievance typically occur with adjunct professors.

“It’s assumed they can’t defend themselves and certainly as individuals, [adjuncts] have a problem defending themselves because they’re not so much subject to being fired, they’re subject to being nonrenewed, which is a very quiet, under-the- table way of getting rid of someone because it’s sort of a nonevent,” Nelson said.

The March 14 P-Fac email also said the union can report the grade change request to the AAUP, which will then conduct an investigation and contact college administration about the report.

If the AAUP determines that faculty’s academic freedom was violated, it can place the college on a censure list, according to the email.

The AAUP could not be reached for comment as of press time. Brenner said it is important students get the most out of their tuition money and to set high standards for both students and instructors, something she experienced also while attending Columbia as a graduate student from 2001–2005.

“Part of having a syllabus is so that we treat all students fairly,” she said. “I want to make sure students are getting their money’s worth, and that means that we do hold them to standards,” Brenner said.