Featured Artist: ‘Loving Vincent’ painter Dena Peterson

October 20, 2017

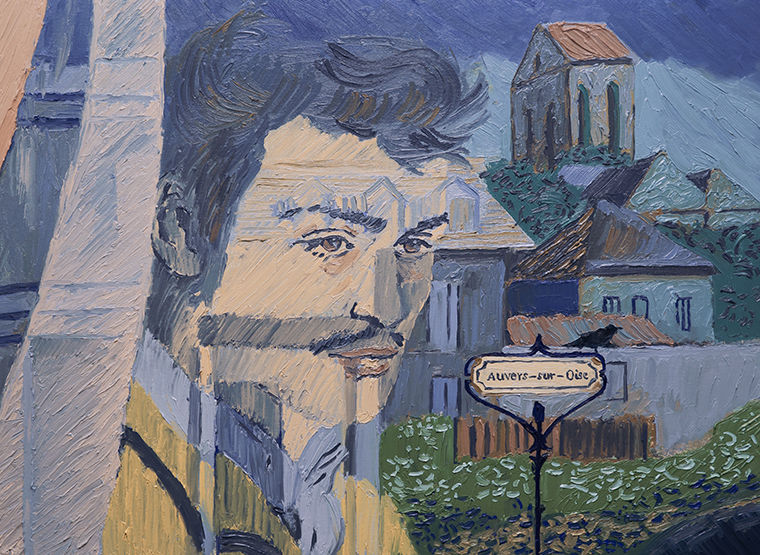

Painter Dena Peterson was one of 125 selected artists out of 5,000 applicants to animate “Loving Vincent,” the world’s first oil-painted feature film, which explores the life and death of Vincent Van Gogh. Peterson, of Colorado Springs, Colorado, worked at the film studio in Poland for six months and painted five scenes.

The Chronicle spoke with Peterson about her contributions to the film.

THE CHRONICLE: What was the most challenging part of creating the film?

DENA PETERSON: I’ve been a painter for at least 20 years, but I [had] never animated before. I got the idea of painting in the style of Van Gogh quickly, but learning how to animate. Everything was all hand-painted, but we had to learn how to put photographs of our work into a software called Dragonframe, and that took me a while as well.

Did you have a favorite scene that you worked on?

[Armand, the main character is] in the wheat field pondering Vincent’s death. He’s by himself, he picks up a stick [and] throws it into the field and it makes the crows start coming out of the wheat field and flying into the sky. It’s based on Van Gogh’s iconic “Wheatfield with Crows.” That particular scene was the director’s favorite scene, [so] it was cool she trusted me to do that.

How was this different from other projects you’ve done before in terms of painting?

My personal style lent itself pretty well to learning to paint in the style of Van Gogh. I like the impasto brushwork; I don’t like painting things in [an] extremely high detail, realistic way. The difference was trying to study his brush work and get into his head to paint more like him, to pay tribute to his work and trying to keep myself out of it.

Was there any special research you did to get into Van Gogh’s head?

On my way over to Poland, I got the audiobook “Letters to Theo” [Van Gogh’s brother], and listened to that all the way over there. I think that in addition to studying his work—especially looking at the high-resolution images, we could zoom in on the brush work and that helped me understand them. I appreciate him more, even after the film, than I did before.

What do you appreciate even more about him now?

His originality, That’s the first thing that comes to my mind. He studied the basics of drawing, and then painting. He learned how to copy what he saw but then took it to a completely new level. He didn’t believe in copying what he saw. He believed in painting what he felt.

How do you evoke emotion as opposed to copying reality?

I [first] learned to paint more realistically. Those are important tools to have in your toolbox as an artist—to know how to study and to copy what we see—but I feel it’s important to learn those things and be willing to let them go. Not completely, but to create paintings rather than photographs. Pushing color a little bit more, emphasizing abstract shapes a little bit more.

Are your paintings of your own emotions or are you trying to bring something out of your audience?

You probably can’t help but have it be your own emotions. We don’t really know what the viewer is thinking or feeling. All we have to work with is our own interpretation of what we’re painting.

Is there something you relate to in terms of Van Gogh’s struggles?

This idea of people expecting us to paint an exact copy of what we’re seeing, the struggle of art as: Do we paint to sell or do we paint what we want to paint? He was struggling with those notions. And the second thing is he’s a sensitive soul. He describes himself as suffering from melancholia and what we might call depression. I’ve struggled with that to a mild degree myself, and I relate to those struggles and the intensity of feelings he sometimes had.

“Loving Vincent” is described as a labor of love. Do you agree with that?

Absolutely. It was hard work. We were expected to paint like Van Gogh, which is a little more emotional and spontaneous. At the same time, the animation part was very meticulous, and you had to be very focused for that, and that was intense work. Studying the movement of the actors and making sure we did it right it was quite a lot of concentration. We spent eight to 10 hours everyday in these little cubicles working on [the animation]. It was definitely something that was hard work and exhausting, but it was for a project that I really believed in. Now having seen the film, it couldn’t have turned out better.

Would you do something like this again?

I don’t know if this particular kind of animation can ever be done again. The [painting of the film] took probably two to three years just because it’s so slow. The director said at one point, this is the slowest form of filmmaking ever, and I don’t think the director, [who] came up with the idea, realized how long it was going to take. If I could do it in a way that didn’t take me away from home for so long, I might be able to do it again. I don’t know how you could do another one because it’s more about the process because it’s so new and so visually unique, and I think Van Gogh’s work lends itself to this because he already had a lot of movement in his work.