George Takei to speak on WWII internment camps

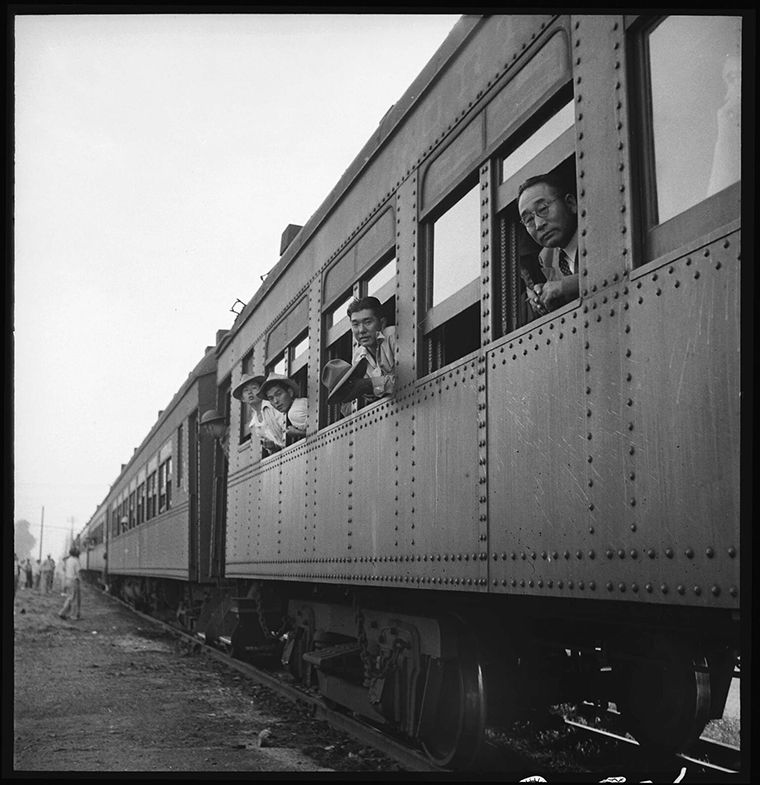

Alphawood Gallery curated photographs that preserve the history of the Japanese-American incarceration during World War II, which reminds the audience what has happened and what could happen.

September 5, 2017

“Then They Came For Me,” Alphawood Gallery’s current free exhibit, relates the story of Japanese-American incarceration during World War II. To add another perspective, actor George Takei is scheduled to share his family’s story at the exhibit.

The Sept. 7 discussion, An Evening with George Takei, will be at The Athenaeum Theatre, 2936 N. Southport Ave. Profits from its $15 admission fee will go to the Japanese-American Service Committee to help it continue its work preserving and remembering Japanese-American history. The exhibit has been running since June 29 and will end Nov. 19.

“It’s really easy to create national myths and pitch ourselves as a certain type of America and to remember ourselves perhaps too rosily,” said Claire Fey, Alphawood Gallery manager. “If we are confronted with the really hard realities and the really disturbing truths of our actual history, it doesn’t allow us to continue with these national myths.”

Under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, the government forcibly relocated more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent from the Pacific Coast to 10 concentration camps in the nation’s western interior; two-thirds were U.S. citizens. This mass incarceration lasted about four years.

Gale Ito attended the exhibit Aug. 27; her mother experienced the camps at 16 years old. She said the moment is seldom mentioned in American history classes and found just one line about it in her daughter’s history textbook.

Fey said the group collected photographs and artifacts to tell the story in multiple perspectives partnering with JASC’s archival resources. Fey said art allows people to see more clearly, adding that photographs look viewers directly in the face and do not allow them to forget what happened in the camps.

“[The stories] demonstrate the problem of when the government takes an action which is racially biased and puts [communities] into a camp under the pretext of national security,” said scientist Roy Wesley, who was born the day his family was scheduled to be moved to an assembly center, a temporary camp used while permanent camps were built.

History forgotten often repeats itself, and the gallery emphasizes on the importance of learning from mistakes, according to Fey.

“Trump is banning Muslims essentially,” Ito said. “There are many similarities brought to light by [the exhibit], and it’s important that people recognize this isn’t the first time it’s occurred.”

Michael Takada, CEO of JASC, said art is a tool to make information more accessible to the community.

“It’s important for society to express this information in all manners possible,” he said. “[Art] touches people intergenerationally, intersections across socioeconomics.”

Takei experienced the camps as a boy and has long been a vocal advocate for education. Fey said his story will help illustrate why remembering is important and impactful to the nation today.

Fey acknowledged the political climate’s overwhelming nature but said there are various ways an individual can strive for and affect change. Asking how to channel one’s energies toward a cause and personalize it, instead of trying to make a specific grand impact, is a sound approach, she added.

“A big personal responsibility of white people is to confront racism whenever they see it,” Fey said. “Rather than closing yourself off from those kind of conversations, which is a privilege that white people do have, try and talk to them on a human-to-human level.”