Plant virus in humans makes brain function wilt

Plant virus in humans makes brain function wilt

November 10, 2014

Microorganisms the human body comes into contact with play a role in determining the health of the immune system and whether or not people become sick. However, these organisms invisible to the naked eye also actively influence how people feel and think.

In a study published Oct. 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers analyzed DNA taken via throat swab from individuals whose cognitive function was assessed using a variety of tests. Shotgun genetic sequencing was used to divide longer DNA strands into short ones, filtering out the human DNA from the samples and leaving behind infectious agents that may be related to impaired mental performance.

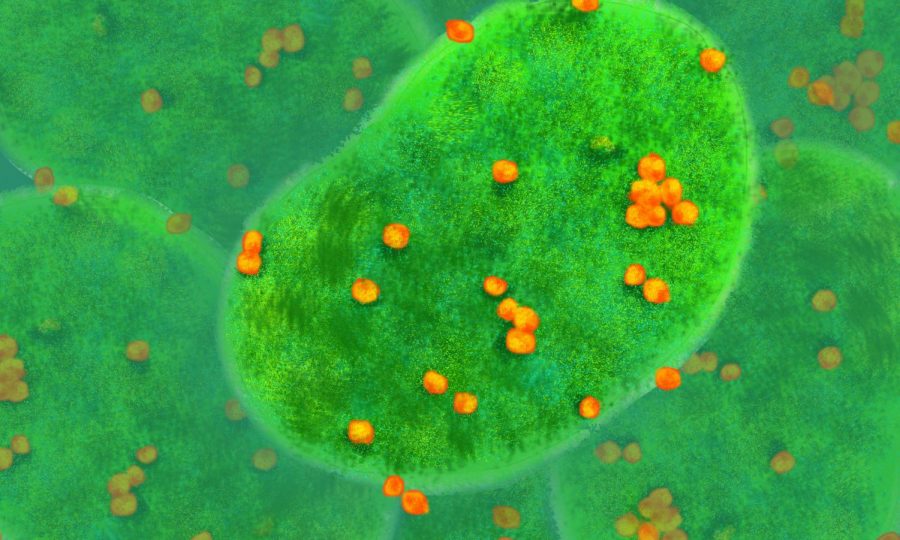

The DNA readings revealed a type of chlorovirus—ATCV-1—previously thought to only affect algae.Its presence was related to a statistically significant impairment of brain function in both the humans who unknowingly carried it and mice that were later fed chlorovirus-containing algae.

ATCV-1 will replicate itself in an algae cell about 1,000 times within a 6–8 hour period following infection, according to James Van Etten, co-author of the study and professor of plant pathology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Van Etten was involved in the discovery of chloroviruses.

“Within a few minutes of the chlorovirus attaching to it, an [algae] cell has effectively died,” Van Etten said. “But the virus keeps the cell alive long enough to complete its replication.”

Researchers are currently uncertain how the study participants initially contracted the plant virus, but Van Etten said an unknown microorganism host or simple contact with a water source are both possibilities for contraction.

“These [chloroviruses] are very common in nature,” Van Etten said. “An individual might once in a while have the viral DNA in their throat swab if they drink some water out of a pond, but the fact that it is this prevalent and seems to have an influence on cognitive function is a total surprise.”

Dr. Robert Yolken, co-author of the study, professor of pediatrics and director of the Stanley Neurovirology Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, said once the virus was found in humans, inoculating mice by feeding them infected algae helped determine whether ingestion of the algae would lead to of viral infection. It would also help determine whether cognitive impairment was consistent between mice and humans.

“[The tests] had to do with visual memory—how well the mice would remember where they were in a maze,” Yolken said. “It’s often associated with the hippocampus.”

More than 1,000 genes were adjusted when the mice were exposed to ATCV-1. These changes in gene expression resulted in impairment of navigation, spatial memory and recognition memory.

“On average, people with the virus had perhaps a 5–10 percent decrease in the domains [of brain function] we measured,” Yolken said. “That’s probably not noticeable in day-to-day conversation or activity, but is significant.”

According to Yolken, this instance of chlorovirus infection is the opposite end of the spectrum from the acute infectious agents that cause noticeable illness, such as influenza or Ebola.

“People probably have viruses like this for long periods of time, and the effects are very subtle, but it is another aspect of viral infection in humans and animals,” he said.

Microorganisms play a role in maintaining all aspects of human health, according to John Cryan, professor and chair of the Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience and principal investigator at the Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre at University College Cork in Ireland.

“Studies over the years show that bacteria in the gut can significantly influence brain function,” Cryan said. “Animals that lack any bacteria have major deficits in neurodevelopment, stress response and cognitive function.”

Although it has been established that impairment of memory, fear learning and anxiety can be affected by a presence or lack of certain strains of bacteria, Cryan said all circuits of the brain could be influenced by microorganisms in the body.

“We’re still working out the question of how the bacteria are signaling these changes in the brain,” he said. “We do know that manipulating bacteria can alter the gene expression of factors in the hippocampus related to cognitive processes.”