CBMR founder, provost remembered for work, kindness, legacy

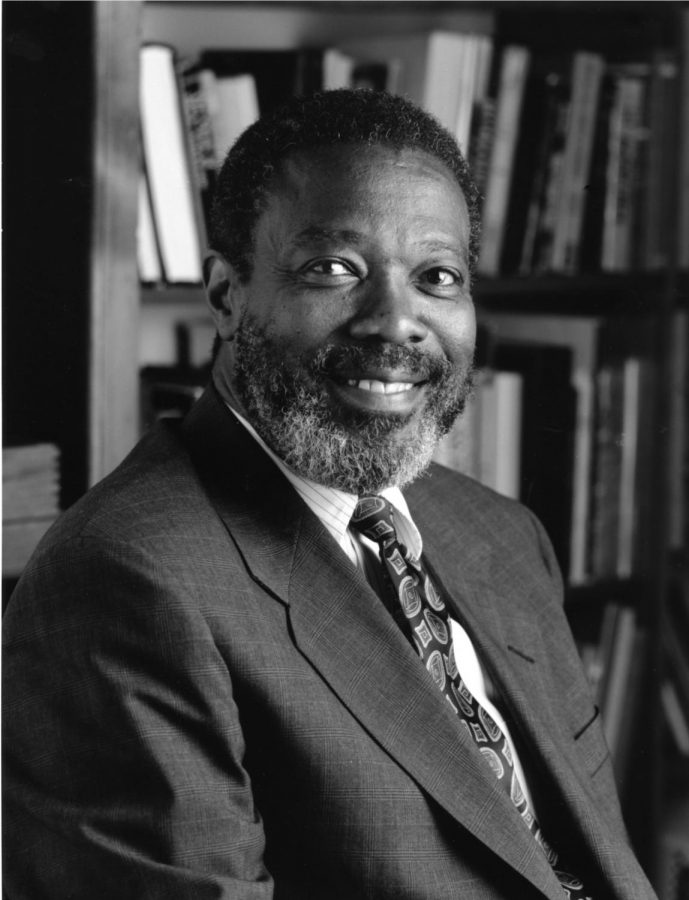

Courtesy CENTER FOR BLACK MUSIC RESEARCH

Samuel A. Floyd Jr., former interim vice president of Student Affairs and provost, academic dean, and founder and director of the Center for Black Music Research, died July 11.

July 21, 2016

Samuel A. Floyd Jr., former interim vice president of Student Affairs and provost, academic dean and most notable for founding the Center for Black Music Research, died July 11 after suffering from second-stage aphasia for more than a decade.

Floyd is survived by his wife, Barbara Floyd, and three children—Cecilia Floyd-Carruthers, Wanda Floyd and Samuel Floyd III—four grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Floyd-Carruthers, 55, said that as busy as he always was, her father always made time for his family and, along with her mom, was her best friend. She added that although her father kept to himself a lot, he was very generous and willing to help anyone who needed it.

“He joked around a lot with us,” Floyd-Carruthers said. “He was like the fourth child in the family.”

While Floyd always made time for his family, he also worked hard to create the legacy of the CBMR and all of its related programming.

During his time with the CBMR, Floyd created four professional ensembles to enhance the center’s programming, brought with him the “Black Music Research Journal,” which he founded in 1980, and raised funding to open the CBMR Library and Archives in the 623 S. Wabash Ave. Building in 1990—before it moved to its present location at 618 S. Michigan in 2009, according to Heidi Marshall, head of Archives and Special Collections.

Floyd also served as director emeritus of the CBMR in 2002 when he retired.

Rosita Sands, interim chair of the Music Department and interim director of the CBMR, worked with Floyd when she joined the college as associate director of the center in 2000 and said Floyd’s establishment of the center was a “bold move” because of its uniqueness.

“[The center] was unprecedented because there was no other institution, and there still is none, that really documents the entire spectrum of black music across time, different regions of the world, various cultures and all the styles and genres of music,” Sands said.

Floyd-Carruthers said her family spent a lot of time around music as a result of her father’s work, and her and her siblings would put on performances based on music he shared with them. She said when Floyd finished his dissertation, he paid his children a quarter each to set up an assembly line and help him put it together.

Floyd’s granddaughter, Kendra Carruthers, 26, said her grandfather was always working on his books or research whenever she would visit, and it was his background in music research that “sparked” her interest in writing about music and entertainment.

“I’m really thankful I got that from him,” Carruthers said. “I would ask him to look over papers I was working on and get his insight, and it was always interesting to hear his input because there’s a huge generational gap [between us].”

In a July 19 collegewide emailed statement, Senior Vice President and Provost Stan Wearden praised Floyd’s contributions to the college and their importance to the greater music community. He said Floyd will be missed.

“The spirit of his work transcends genre and time, and continues to allow us to trace our histories and musical lineages across geographies and generations,” Wearden said in the statement. “In this, we as a college community view his legacy as an inseparable part of us. He made remarkable contributions to Columbia, to music, and scholarship, and we are grateful Columbia was his home for so long.”