New Cornell study shows consumers may overly trust graphics

Graphic

October 27, 2014

An Oct. 16 study from the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab has found that consumers may be too trusting of graphics accompanying medical products.

The study reveals that graphs or formulas accompanying medical information can lead consumers to believe products are more effective.

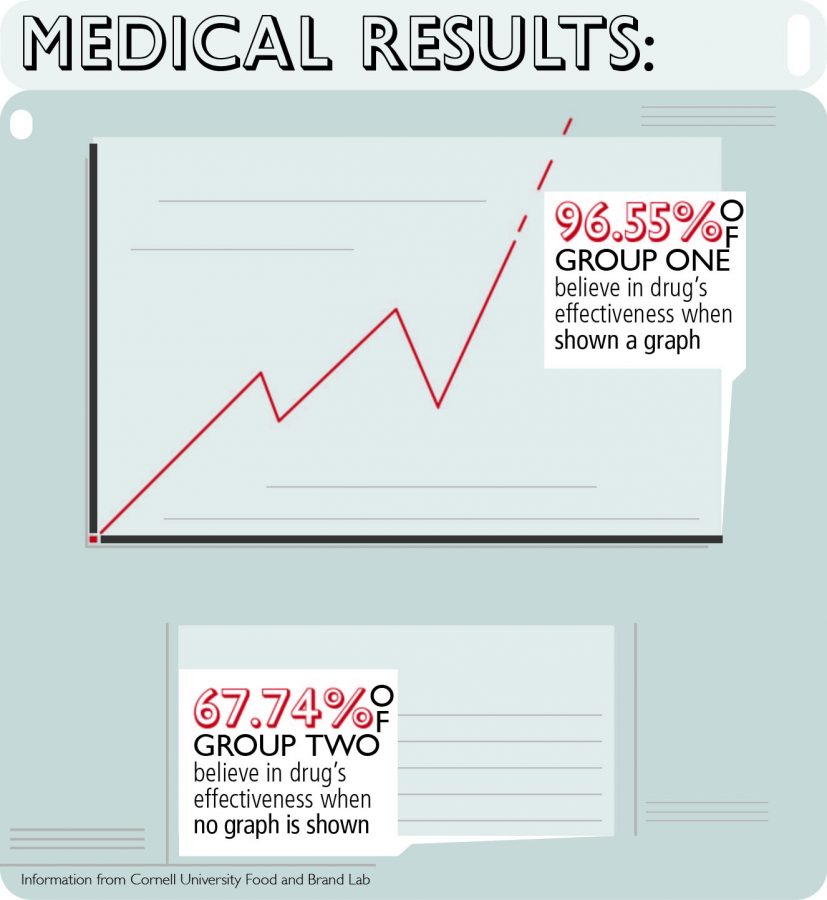

Participants were shown information about a new medication that is said to enhance immune function and reduce the occurrence of the common cold. Participants were randomly assigned to two groups, one of which was shown a graph with the information, while the other was not.

More than 96 percent of the participants in the group that was shown the graph believed the medication would effectively treat illness. In the group that did not see a graph, that number decreased to roughly 67 percent of the participants who thought the medication would reduce their illness .

Aner Tal, researcher for the Lab and co-author of the study, said numbers can make a product seem more official.

“When I was giving academic presentations in grad school, I was always encouraged to include graphs in them,” Tal said. “Part of the reason for that is because some people are more visual thinkers, and it’s easier for them to process information when you give it in a graph, versus verbally or in numbers. But I had intuition that part of that might [be] because you somehow look more serious when you have figures and graphs and tables with numbers in them and so on.”

The graph that participants were shown contained no new information about the medication but simply gave a figure and showed separate columns for drug and control groups, with a 40 percent reduction in incidence of illness between the two groups.

Tal said the results show that numbers are just one of several factors that can affect a consumer’s trust in a product.

“Numbers, pictures that look scientific [and] scientific-sounding language can all have an effect because they signal to people that the source of the information is credible, basically,” Tal said. “They tell someone that this information comes from science, in a way. So [the graph numbers] makes it more real or trustworthy.”

Tal also said although the numbers on labels does often translate into increased product trust from consumers, it is not the biggest component.

“If you’re looking at brain images, then it makes sense that that information wouldn’t be acceptable to everyone because you need to have some background,” Tal said. “When it comes to a graph that’s easily readable, it’s not necessarily a question of education. It’s just, ‘What does the presence of that element say to you?”

It is not just visual information on medication that is making consumers feel more comfortable, though. An Aug. 17 Motley Fool article stated that labels like “gluten-free” or “all-natural” make shopping difficult for consumers because the standards are not as exacting as most consumers believe them to be.

Kate Merkle, a registered dietitian, said reading ingredients can help combat faulty labels.

“I [oftentimes] guide my clients to review the ingredients list,” Merkle said. “That can be a nice indicator. When the ingredients list is as long as their arm and they can’t identify a lot of the ingredients, that’s a really easy indicator that [something] isn’t a whole food [and] probably isn’t the healthiest choice to be eating daily.”

Merkle also said it is important to teach people how to shop because most grocery stores are set up the same and knowing which sections to avoid can help consumers.

“In every grocery store you go into in the whole U.S., the perimeter is where you’re going to find the whole foods—your meats, your proteins, your fruits and vegtables—” Merkle said. “The insides of the aisles are going to be more of your packaged, boxed foods. Just getting people to open up their eyes of how the grocery store is laid out is a really helpful piece to getting their behaviors to change.”

Judy E. Manisco, a licensed dietitian and nutritionist, said she does not feel that faulty labels are the biggest problem facing food consumers but rather the portion sizes.

“The problem is that portions in restaurants and fast food are too big,” Manisco said. “Even the soda portions. I think when you go into restaurants, [the portions] are double what they should be eating.”

Manisco also said it is important that parents teach their kids early on how to properly eat healthy and which foods to consume.

“I think that children—as soon as they are able to comprehend and absorb and really think of it as something fun—should all be taught in grade school about nutrition,” Manisco said. “But the biggest thing is about the parent. If the parent is not doing [it], it’s really going to be difficult for any child at home to stick [to eating health] and have success with it.”