French World War I illustrations march into public eye at University of Chicago

En Guerre

October 27, 2014

The University of Chicago will be commemorating the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I with an exhibit titled “En Guerre: French Illustrators and World War I” at the Special Collections Research Center Exhibition Gallery, 1100 E. 57th St., through Jan. 2.

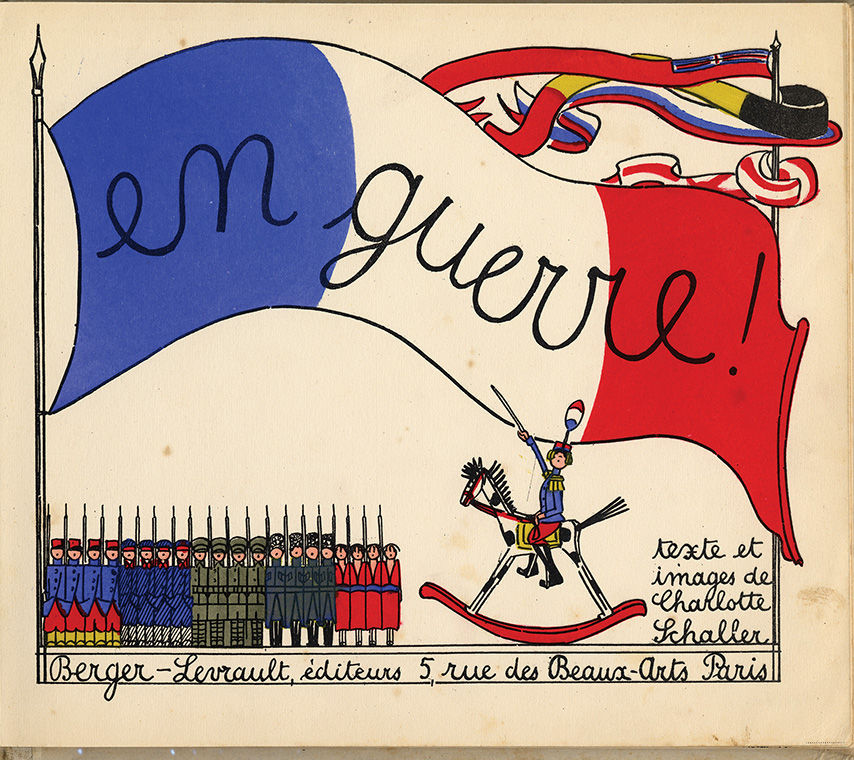

“En Guerre,” which derives its name from a book on display in the exhibit by French illustrator Charlotte Schaller, is curated by Teri J. Edelstein, an art historian, and Neil Harris, professor emeritus in the History and Art History departments at U of C. The exhibit features work produced entirely by French illustrators from shortly before to just after World War I, which was fought from 1914–1918. The collection is made up of pieces from both Edelstein’s and Harris’ personal collections, as well as a few pieces from collections at Brown University and the University of Pennsylvania as well as

another private collector.

Edelstein said the exhibit has been in the works for nearly four years and despite its coincidence with the 100th anniversary of the war, Edelstein and Harris had no special interest in the event when collecting the illustrations.

“This year is the centenary of the start of World War I,” Edelstein said. “Neil Harris and I have collected for many years, [and] although World War I was not anything of particular emphasis of ours, we noted that there were a great many important works that were published about [the war] by important illustrators.”

Most of the illustrations in “En Guerre” were a byproduct of French patriotism during the war rather than official commissions, Edelstein said.

“None of this is official,” Edelstein said. “None of this was done for the [French] government. None of it is officially propaganda. It’s all propagandistic. It’s all about the war—not all of it is positive. Some of it is critiquing the war, but absolutely none of the pieces in the exhibition were commissioned by the government.”

Shannon Fogg, associate professor in the History Department at the Missouri University of Science & Technology, said the nations of Europe were so patriotic and willing to go to war because there had not been a war in Europe since the Napoleonic wars, which was about 100 years earlier.

“[Going to war] was actually not that surprising for most European nations in 1914,” Fogg said. “They knew that war was coming and a lot of young men went to war very enthusiastically and were sent off with the support of their families. It was seen as a great adventure.”

Ara Merjian, associate professor of Italian Studies and an affiliate of the Institute of Fine Arts and Department of Art History at New York University, said France had a “coalescence of illustrated magazines” during the war, and the magazines became an outlet for both illustrators and artists of the avant-garde movement.

“A number of these [French] journals were on the same position of the spectrum politically,” Merjian said. “Whether in terms of French nationalism or a more pacifist internationalism, as there was with poster design … there was a certain permeability and mutual influence between a number of the cartoonists and satirist and the members of the French avant-garde.”

Edelstein said despite some of the illustrators creating great pieces following the war, many of these artists remain unknown.

“Very few people know about these artists,” Edelstein said. “Even my colleagues at the Art Institute who are experts in the field of early 20th century French art have never heard of these artists.”

Along with giving exposure to the illustrators and their work, Edelstein said she and Harris wanted to educate people about World War I.

“We wanted people to know more about the war,” Edelstein said. “We wanted people to know more about these illustrators, so both of [those] were very much a desire on our part.”