Immigration policy shift affects more than DACA

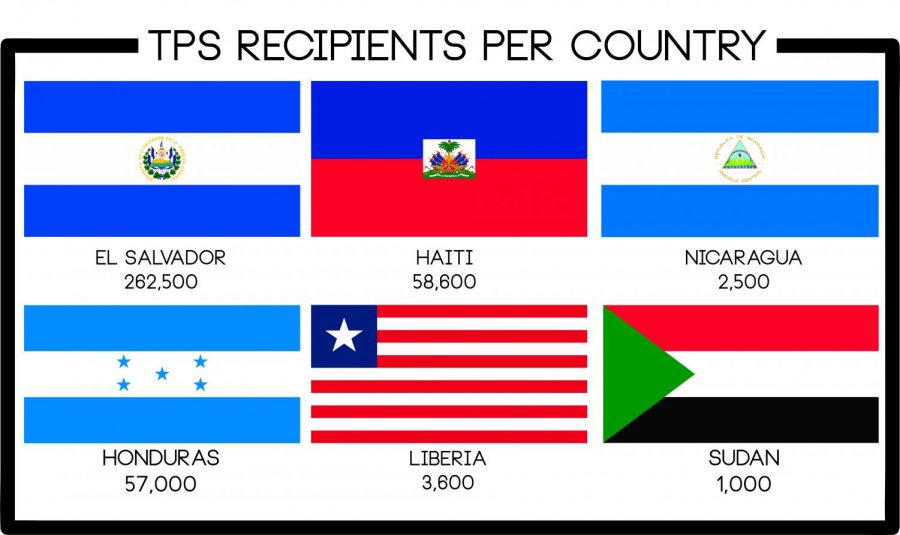

Info courtesy U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

April 16, 2018

With the fate of Dreamers still in question, the temporary-status immigration programs for Liberians, El Salvadorans, Haitians, Hondurans and Sudanese have been canceled—potentially uprooting more than 300,000 people nationwide.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security announced an end to the Deferred Enforcement Departure for Liberia March 27, giving beneficiaries of the program a 12-month grace period before the program officially ends, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. The decision could affect 3,600 Liberians, who were granted Temporary Protected Status during the Liberian civil war more than 20 years ago.

The Trump administration is attempting to fulfill its more restrictive immigration policy promises made during the campaign, said Alexandra Filindra, a professor of political science at the University of Illinois at Chicago and expert in immigration policy. While some campaign promises, such as the U.S.-Mexican border wall, require funding from Congress, cancelling programs are within the White House’s authority, she added.

“[Trump] is changing these programs that are meant to protect populations that escaped civil wars or natural disasters,” she said. “Their return [to their home countries] would be a huge problem. Especially for Liberia because these people have lived in the United States for decades.”

Jennifer Brumskine, a chairman for the immigration committee at the National Association for Liberians in the Americas, called the decision “inhumane.” The DED beneficiaries contribute to American communities, education and government, she said.

Brumskine said she is worried the motivation for the administration’s policies might be “deeply rooted in white supremacy.”

“Many of these people came from Liberia with nothing, and they have nothing to go back to,” she said. “They left their homes with nothing on their back and ran for their life.”

El Salvador is the largest group of TPS holders with about 260,000 people who have until Sept. 9, 2019, to change their immigration status, leave the U.S. or face deportation, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Yanira Arias is a TPS holder from El Salvador who works as a campaign manager for Alianza Americas, a network of Latino and Caribbean immigration organizations.

After leaving El Salvador in 2001 after two deadly earthquakes and a civil war, Arias received TPS status in 2001 but was unaware that it does not allow her to become a citizen or permanent resident, she said.

A work permit allowed Arias to pay bills and support her family in El Salvador. Despite TPS recipients paying taxes in the U.S., they are not allowed to file tax returns or receive benefits from the local and state programs they fund, Arias said.

Because Arias is not married and has no U.S.-citizen children, she has few options to keep her in the country after the program expires.

El Salvador is the country with the highest rate of violence in the Western hemisphere, Arias said, adding that the TPS community does not think one year is enough time to consider their options before possible deportation.

“There is a lot of uncertainty and fear [in the community],” Arias said. “People don’t want to leave because, if they have U.S. citizen children, they know it is their right to be here in this country, and that education and opportunities are here for them. [They don’t want to] take these children to countries they’ve never been to, where the education is not good and know that [they] will not even be able to walk freely in the streets.”

There are approximately 58,600 Haitians with protected status who will lose their benefits on July 22, 2019, and status for 5,300 Nicaraguan beneficiaries is set to terminate on Jan. 5, 2019. Just more than 1,000 Sudanese TPS holders will no longer be eligible as of Nov. 2, 2018.

“These programs are meant to be temporary,” Filindra said. “Therefore, if the government judges the conditions of these countries of origin have changed, then it is justified in saying it’s OK [for them] to go back.”

However, those who have been away from their native country for years will find it difficult to re-integrate, Filindra said. In some of these countries, such as Liberia, Sudan and El Salvador, the conflict and danger is ongoing.

Removing TPS and DED from communities will have a lasting economic effect, Arias said.

“When you tear down a tree from the roots, the entire ecosystem is connected to that tree. If you’re tearing 250,000 trees [out of the country], that is a serious impact,” she said.

Arias added that because Congress is not taking action to defend these programs, it is the responsibility of the communities to get informed, seek legal counsel, call legislators and make the issue visible.