Advocate organizations carry torch in disability awareness

Advocate organizations carry torch in disability awareness

March 12, 2018

For half a century, the Special Olympics has been raising awareness of the intellectually disabled, but there is still more work needed, according to experts.

To commemorate the Special Olympics’ 50-year anniversary, Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the Chicago Park District broke ground on the Eternal Flame of Hope March 2 on Soldier Field’s north lawn, 1410 Museum Campus Drive. Chicago will also host the anniversary celebration and Special Olympic Games July 17–21, according to a March 2 mayoral press release.

“The Special Olympics Flame of Hope has always been a beacon lighting the way for inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities,” Special Olympics International CEO Mary Davis said in the press release. “The Eternal Flame of Hope monument will be a constant reminder that when in doubt, choose to include.”

Intellectual disabilities are organized into five classifications, said Chad Rollins, assistant executive director for William DeBell ARC, a Wood River, Illinois-based group that works with intellectually disabled people. These categories are borderline, mild, moderate, severe and profound.

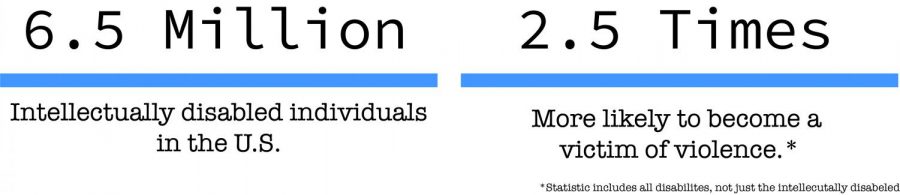

Even with awareness raised by the Special Olympics and the March 4 Polar Plunge, the estimated 6.5 million intellectually disabled individuals in the country are more likely to be victim of hate crimes, according to Rollins.

A July 2017 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics concluded that individuals with disabilities were up to 2.5 times as likely to be a victim of violence in their lifetimes. However, this study includes all disabilities and is not specific to intellectual disabilities.

Because some intellectually disabled people have a difficult time communicating when someone is treating them improperly, Rollins noted the true number of hate crimes against the group may never be accurately known.

“If anybody is discriminated [against], it’s [more likely] out of ignorance,” said Chris Winston, chief marketing officer for Special Olympics Illinois.

Along with the Special Olympics, programs such as the NORA Project—which brings children with intellectual disabilities into the classroom—have made progress in increasing awareness, said Lauren Schrero Levy, executive director of the NORA Project.

Students with intellectual disabilities are normally separated from other students in different classrooms, which can lead to misconceptions about the group, Schrero Levy said.

Both the NORA Project and the Special Olympics have programs and events for children with and without disabilities to interact and help tackle misconceptions early in a child’s life, according to Schrero Levy and Winston.

“A lot of the myths are dispelled [when you interact with more people],” Schrero Levy said. “It’s the same as when you meet any person who may seem different from you. The more we get to know one another, the more we realize we are all fundamentally the same.”

Approximately 60 to 70 percent of Americans are unaware of what intellectually disabled people can do, according to Winston.

As a parent of someone with an intellectual disability, Schrero Levy said she has had more conversations with “more kindness, reaching out and empathetic questions instead of unkind words” in the past few years.

But there is still work to be done, Schrero Levy added, and Winston agreed.

“People are becoming more and more knowledgeable,” Winston said. “Are we there yet? No. But who is there [when it comes to] discrimination? But we are leaps and bounds ahead of where we were.”