Study finds problems with CPD officers in schools

Study finds problems with CPD officers in schools

February 20, 2017

Lack of training and accountability for Chicago police officers assigned to public schools has led to the spending of millions of taxpayer dollars to settle lawsuits and the continuation of the “school-to-prison pipeline,” according to a recent study on juveniles in the criminal justice system.

The study, “Handcuffs in Hallways: the State of Policing in Chicago Public Schools,” on Chicago Police Department’s role in schools as “school resource officers,” was released Feb. 8 by The Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, a Chicago-based advocacy and research group.

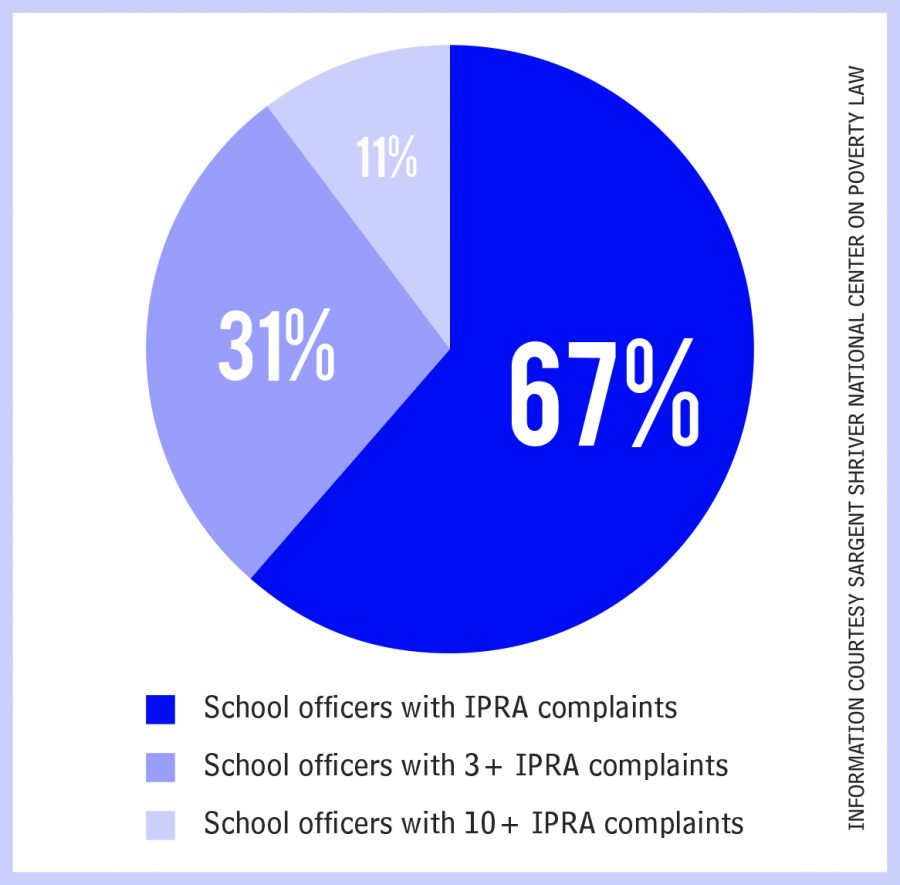

According to the report, 248 police officers are assigned to CPS schools as of April 2016, and their lack of training leads to misconduct. Sixty-seven percent of the officers have had complaints filed against them through the Independent Police Review Authority. Meanwhile, 31 percent had three or more complaints filed, and 11 percent had 10 or more complaints. More than $2 million has been paid to settle misconduct lawsuits between 2012 and 2016, the study states.

Damon Williams, the co-director of #LetUsBreathe Collective—an activist group seeking police accountability—said he was not surprised when he learned about the study’s findings.

“[CPD] does not spend many resources on restorative communal relationships,” she said. “To know these militarized agents are in these schools without any specific guidelines is sadly something I would expect.”

A Feb. 13 emailed statement from CPS spokesman Michael Passman said the district is currently decreasing the number of police and security officers in schools and is creating more social and emotional support avenues for students.

“We appreciate the recommendations brought forward by the Shriver Center,” Passman said. “We will seriously consider all potential opportunities to maintain our safe school environments while further strengthening school climates.”

According to the report, security officers are hired by CPS and required to go through a three-day training course consisting of de-escalation techniques and crisis prevention. However, the school resource officers who are the subject of this report are hired by CPD and only required to have a working knowledge of the CPS Student Code of Conduct.

According to the code of conduct, CPS students have the right to tell their side of the story before receiving discipline or consequences, and school staff has the responsibility to intervene and de-escalate inappropriate behavior.

Police officers in schools could play a valuable role as mentors as long as they receive proper training and education in adolescent psychology and their roles are properly defined, said Candice Hughes, an associate psychology professor at The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

Hughes said it is important for adults working with students to understand child and adolescent psychology because the students they are working with are in their developmental years, and a lack of training could damage students—especially those with mental health issues.

“There are many dimensions of an adolescent’s or child’s life that need to be taken into consideration,” Hughes said. “Some basic training for police officers could not hurt.”

The high numbers of complaints speak volumes to both the lack of accountability and training within CPD, according to Emilie Junge, a Chicago-based attorney who works on criminal record expungement—the legal process of sealing criminal records.

“[Police officers] should absolutely not be in the schools,” Junge said. “We have to start thinking about alternatives to the culture that we have, which is about arrests. It’s about punishment and not about addressing the trauma that children have been through and the need for other approaches.”

Junge said the study and the recent Department of Justice report, which accused Chicago police of civil rights violations of Chicagoans, as reported Jan. 13 by The Chronicle, should provoke an in-depth investigation into CPD practices.

“What is needed are social workers and people who are trained in conflict resolution,” Junge said. “I don’t think criminal justice is the approach that should be used to [solve] disciplinary problems within schools.”

According to the study, the lack of officer training disposes school police to react harshly to students, which “fast tracks” them toward the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

When juveniles are put into the criminal justice system, Junge said, they have a higher percentage of recidivism that could affect a student’s future ability to be employed or go to college.

According to the Cook County Board of Commissioners, the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center is one of the largest in the nation, and Williams said it is a “product” of how CPS and CPD are “failing young people.”

“The school-to-prison pipeline is as distinct and visible as possible here in Chicago,” Williams said. “Young people are used to seeing police officers more than nurses and mental health professionals.”

Williams said he would like to see the communities as well as city officials take a more critical look at accusations of police misconduct in order to understand how “unjust” and “oppressive” it is to place police officers in underfunded schools.

The CPD News Affairs Office did not respond for comment as of press time.

“If we want our children to be safe in schools, we need to invest in making sure there are people there that are serving the actual needs [of students],” Williams said. “[School resource officers] are not serving any needs, they’re just sucking up resources that can be used for someone who can be more helpfully involved in the community.”