Harnessing solar power through the looking glass

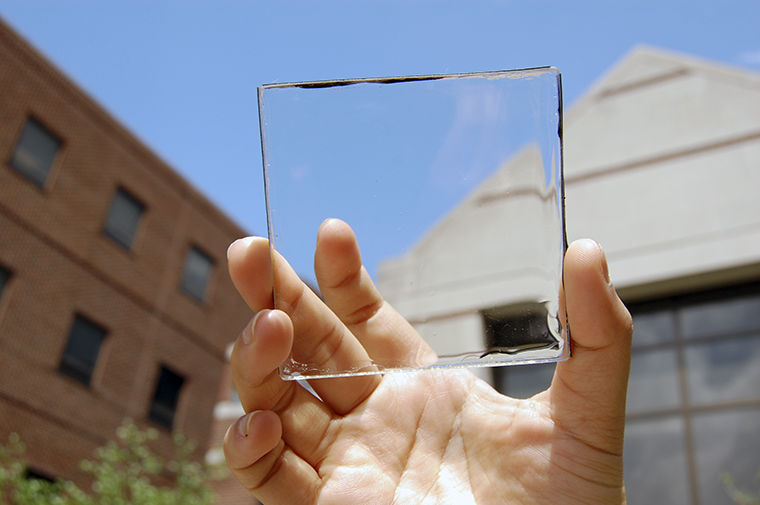

Transparent Solar Concentrator Prototype

September 2, 2014

Researchers from Michigan State University have developed a new solar energy concentrator that, unlike previously constructed luminescent solar panels, does not tint the color of the sunlight shining through it.

An advantage of transparent solar technology is that, while less efficient at its current stage of development, users will reduce the load of lighting in their current household or workplace, according to Richard Lunt, professor of chemical engineering and materials science at Michigan State University.

“If you’re sitting in front of a window, one of the things you might notice is that the level of transparency is very high,” Lunt said.

Lunt explained that while there is a lot of energy in the visible part of the light spectrum, the infrared component not visible to the human eye actually makes up more than two-thirds of sunlight. By constructing a transparent concentrator specifically designed to pick up only non-visible wavelengths of light, the potential amount of electricity generated is only reduced by one-third. This is because visible light is allowed to pass through the glass without being captured and converted into electricity.

“If you consider covering a window with [opaque] photovoltaic solar paneling, you’d be converting light to energy at a loss,” Lunt said. “You’d be using some of that power to then power the lighting inside of the home or office, whereas if you made it transparent and let all of the light shine through, you’d get 100 percent lighting efficiency.”

The trade-off between designing buildings that use solar cell panels instead of windows is that while the opaque solar cell panels generate more energy, no natural light passes through them, according to Amanda Smeigh, program manager at the Solar Fuels Institute and a Ph. D. in chemistry from Michigan State University.

“Putting panels on windows works, but then your window becomes a wall,” Smeigh said. “In one regard you’re getting the best of both worlds—still generating electricity, just not as much.”

Smeigh said this technology provides a good opportunity for offsetting electricity usage in practical settings. For example, architects might cover the roof of a skyscraper in solar cells, which are more efficient but are also limited to operating within a more confined space, and use the transparent panels for the windows.

“You have a larger area of windows [on a skyscraper], so I could see it making a bigger difference in generating electricity than if you were to use only roof-mounted solar panels,” Smeigh said.

According to Lunt, solar concentrators have been around for many years, the idea was first developed in the 1970s. Lunt said the motivation driving the technology was the high cost of solar cells, and finding a method to direct light onto fewer cells would be cost-effective. He explained that researchers embedded a luminescent dye into inexpensive sheeting in order to absorb the different colors of the solar spectrum.

The efficiency of his team’s transparent technology is close to one percent, but Lunt said they believe they can get it to at least five percent, and optimally to seven percent with some additional design work, making its efficiency competitive with that of the more unsightly colored luminescent concentrators. Currently, non-transparent solar panels can reach a maximum efficiency of 25.6 percent, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

“You wouldn’t want to operate in a house with that kind of hideous orange or green light coming through,” Smeigh said. “So the fact that it’s colorless to the human eye is a significant improvement.”

The U.S. has seen an exponential increase in solar technology over the last six years, according to Carly Rixham, executive director of the American Solar Energy Society.

“The categories of solar technology include thermal, passive, concentrators and electric, which solar cells fall into,” Rixham said.

She explained that while one percent efficiency is not an impressive number when compared to the 25.6 percent efficiency the National Renewable Energy Laboratory reports can be obtained with photovoltaic panels, the potential practical application makes the transparent ones very valuable.

“In terms of efficiency, we can’t keep moving the carrot,” Smeigh said. “We can’t keep striving to hit goals without implementing them.”