Gap between rich and poor widens

Information from Brookings Institution

March 3, 2014

In Chicago and other cities nationwide, the gap between the rich and poor is expanding as the economy slowly recovers from the Great Recession, according to a Feb. 20 Brookings Institution study.

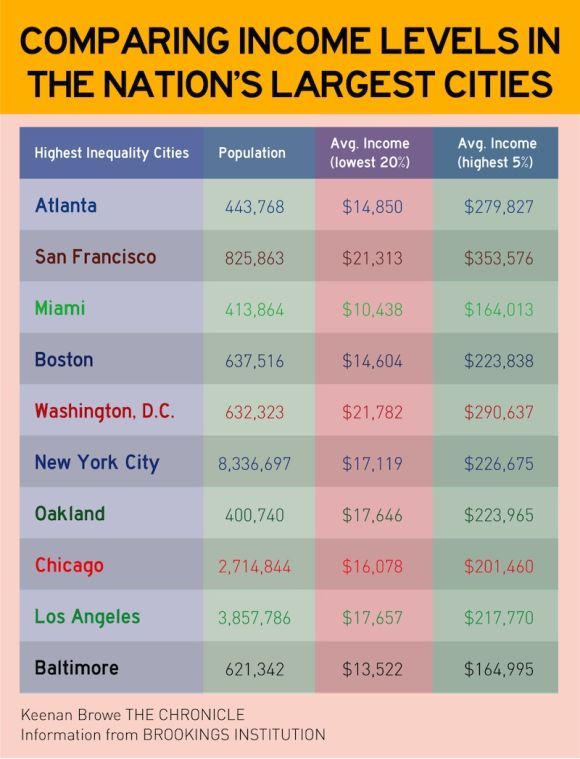

The study, titled “All Cities Are Not Created Unequal,” compared the highest and lowest household incomes in 50 of the nation’s largest cities, as determined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Chicago ranked as the city with the 8th highest income inequality, while Atlanta ranked first on the list, with its highest earners making more than $279,000 annually and the lowest earners making $14,000. Income inequality in major cities outpaces the national average, according to the study.

Edwin Mills, a Northwestern University professor who specializes in urban economic development, said the Great Recession, which began in 2007, impacted the poor more than the rich and contributed to the disparity.

“This long, drawn-out recession has certainly favored income inequality,” Mills said. “Low-income people tend to get laid off and find it harder to find jobs.”

Income inequality results in poor performing schools, lower city tax revenue and reduced employment and housing options for middle- and low-income households, forcing them to leave the city, according to the study.

It is becoming more common for city residents to migrate to the suburbs when faced with minimal job opportunities and unavailable homes, Mills said. In recent decades, suburbs have expanded, making room for more low-income residents than in the past, he said.

“Traditionally, zoning has mitigated low-income people to leave cities because they got zoned out of high-income suburbs,” Mills said. “That seems to be breaking down as suburbs begin to extend farther and farther out, and area suburbs are not so discriminatory against low-income people. Low-income people leave the cities but they don’t usually go out very far.”

Howard Wial, executive director of the Center for Urban Economic Development at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said income inequality can also lead to gentrification.

Wial said factors such as tax rate reductions for the rich and the $7.25 federal minimum wage facilitate inequality. Wial said local minimum wages and the scarcity of sustainable jobs for people without a college degree lead to inequality because there are fewer opportunities for low-income residents.

“Policies that help create … good jobs for people who don’t have bachelor’s degrees are helpful,” Wial said. “The efforts that are just getting started around here … could be helpful, but we haven’t had much of that in the past decade or earlier.”

Wial said it was recently announced that the Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute will be established in Chicago, providing more job opportunities for people without bachelor’s degrees by making digital literacy training available to workers looking for employment.

Although Chicago appears unequal, Wial said high inequality is to be expected because it characterizes the nature of a city. Cities offer both high-income jobs and minimum-wage jobs, which attracts a diverse demographic.

“Even in the best possible world, where inequality was as low as you could ever imagine it could be, places like Chicago would still have more inequality than places like Peoria, Ill.,” Wial said. “The fact that Chicago looks relatively bad in terms of inequality is not necessarily Chicago’s fault and not necessarily a flaw in the functioning of the economy.”

Aileen Kelleher, communications director for Action Now, a local social justice organization advocating to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour, said Illinois’ current minimum wage, $8.25 an hour, encourages income inequality because it is not a living wage, causing most minimum-wage earners to live in poverty.

Kelleher said other Chicago initiatives, such as downtown development, exclude low-wage workers and force them to relocate to low-income neighborhoods on the South and West sides.

“If the minimum wage was raised, there would be more jobs that paid closer to what people and contribute to closing the income inequality gap,” Kelleher said.