Centennial celebrates renowned Chicago poet

Courtesy University of Michigan Press

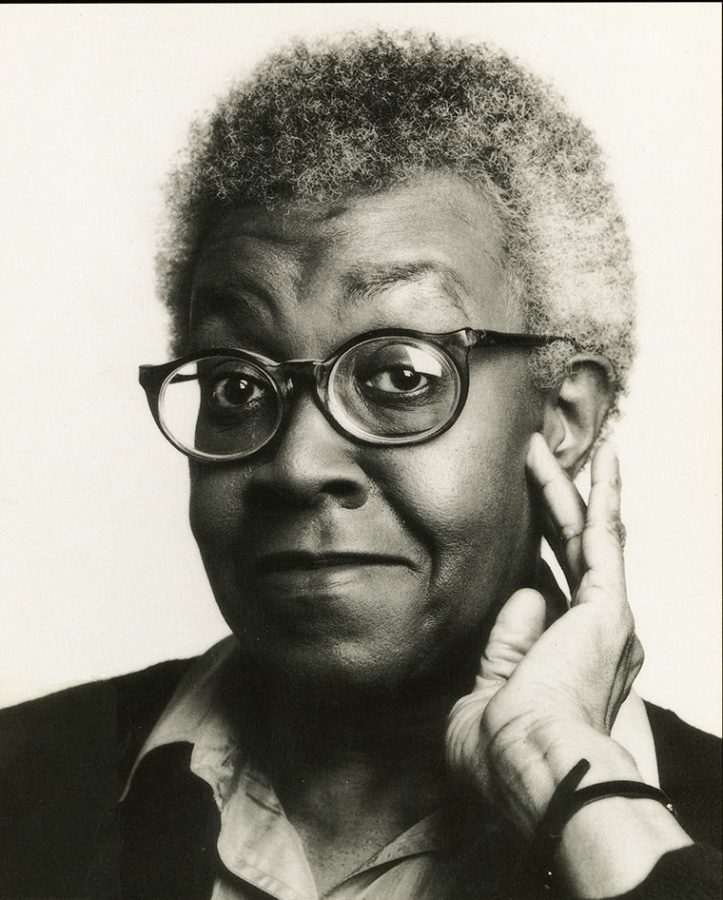

Gwendolyn Brooks

January 30, 2017

Archivist Meg Hixon has been immersed for two and a half years in poet Gwendolyn Brooks’ correspondence with fellow Illinois poet Langston Hughes, and others, in order to introduce audiences to the writer and her work.

Hixon is often struck by how gracious Brooks was with the public.

“One thing I appreciate the most is how much Gwendolyn Brooks appreciated her fans, particularly children,” Hixon said. “She was really great about fan responses and would write responses on a piece of notebook paper and staple it to the original letter.”

Hixon, the archival and literary manuscript specialist for the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has been living and breathing the archives—which Hixon estimates take up about 250 feet of shelf space—since she began her work at the university in 2014. Her goal is to have all of Brooks’ material archived by Summer 2017, which would have been the official centennial of Brooks, who was born June

7, 1917.

One hundred years after her birth and almost two decades after her death in 2000, Brooks’ flame still burns bright. The Gwendolyn Brooks Centennial begins Feb. 2 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Reading events and performances centered on Brooks will be part of the celebrations.

Poet Quraysh Ali Lansana, one of Brooks’ last mentees, conceived the reading event, Our Miss Brooks, sponsored in part by The Poetry Foundation and the Community Trust Foundation.

“Brooks, in my mind, has been understudied and undervalued in the literary canon,” Ali Lansana said.

Brooks, the first black person to receive a Pulitzer Prize in 1950 for her 1949 book “Annie Allen,” is celebrated throughout Chicago and the country for her work as a poet, author, feminist and mother who often wrote about racial issues, social justice and women’s rights. Brooks’ teaching career, which began in the early ‘60s, brought her to Columbia, Chicago State University, Northeastern Illinois University, Columbia University and the University of Wisconsin.

Born in Kansas but raised in Chicago, Brooks’ passion for reading and writing started at a young age, and she quickly entered the city’s literary community that would later celebrate her successes.

Ali Lansana, an award-winning poet, author and lecturer in SAIC’s Creative Writing Department, served as the director of the Gwendolyn Brooks Center for Black Literature at Chicago State University from 2002 to 2011. He is also co-editor of the anthology “Revise the Psalm: Work Celebrating the Writing of Gwendolyn Brooks,” alongside Sandra Jackson-Opoku, also an award-winning poet, writer and journalist who writes frequently on culture and travel in the African diaspora.

The book, published Jan. 17 on Curbside Splender, pays homage to Brooks’ writing and activism through essays and poems inspired by her work.

Ali Lansana, also the artistic director of the citywide initiative Our Miss Brooks 100, said Brooks’ race, gender and career decisions affected her portrayal by the larger community. He said publishing the anthologies in time for the centennial aims to change Brooks’ public perception and re-energize her value in the literary conversation.

“Brooks is one of the most important writers of the 20th century, but many people do not know who she is,” Ali Lansana said. “Many people only know her by ‘We Real Cool,’ which is an often-anthologized poem which she grew to loathe for

that reason.”

The Feb. 2 event, which will feature five black Pulitzer Prize-winning poets including Rita Dove, Yusef Komunyakaa and Natasha Trethewey, is just one of more than 30 events happening this year in Chicago to commemorate Brooks, Ali Lansana said.

Elizabeth Burke-Dain, director of marketing and media at the Poetry Foundation, said Our Miss Brooks 100 will occur throughout the year with dance performances from the Joffrey Ballet and a play by Manual Cinema based on Brooks’ life, as well as a June 7 display of Brooks’ archives at the Foundation that Hixon is working to complete.

Burke-Dain said the centennial clearly demonstrates that Brooks’ words live on, but her close Chicago ties lift her up on a high pedestal.

“[Brooks] is a Chicago daughter,” Burke-Dain said. “The uniqueness of her voice influenced both black and Caucasian poets. The ideas that she [covers] in her writing, we are still experiencing them now, so her poems seem fresh today. [She] still has so much to offer us and we thank her for that.”