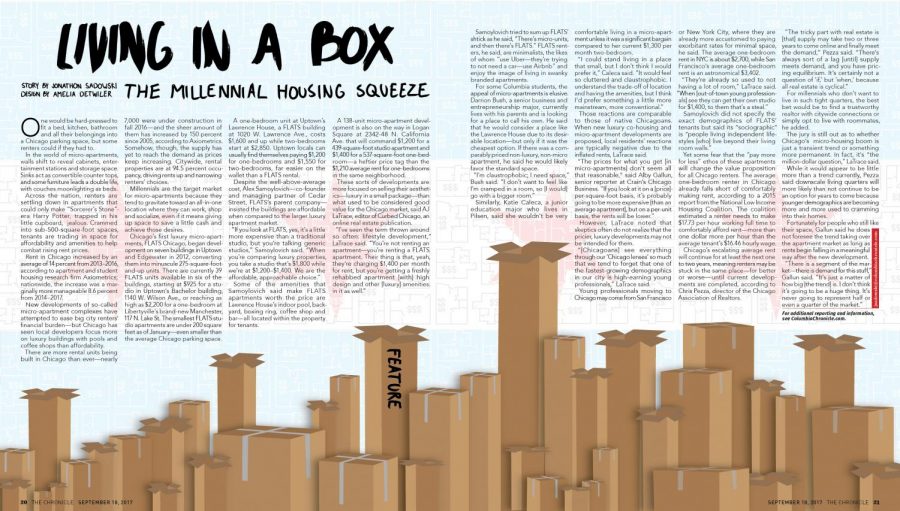

Living in a box: the millennial housing squeeze

September 18, 2017

One would be hard-pressed to fit a bed, kitchen, bathroom and all their belongings into a Chicago parking space, but some renters could if they had to.

In the world of micro-apartments, walls shift to reveal cabinets, entertainment stations and storage space. Sinks act as convertible counter tops, and some furniture leads a double life, with couches moonlighting as beds.

Across the nation, renters are settling down in apartments that could only make “Sorcerer’s Stone”-era Harry Potter, trapped in his little cupboard, jealous. Crammed into sub-500-square-foot spaces, tenants are trading in space for affordability and amenities to help combat rising rent prices.

Rent in Chicago increased by an average of 14 percent from 2013–2016, according to apartment and student housing research firm Axiometrics; nationwide, the increase was a marginally more manageable 8.6 percent from 2014–2017.

New developments of so-called micro-apartment complexes have attempted to ease big city renters’ financial burden—but Chicago has seen local developers focus more on luxury buildings with pools and coffee shops than affordability.

There are more rental units being built in Chicago than ever—nearly 7,000 were under construction in fall 2016—and the sheer amount of them has increased by 150 percent since 2005, according to Axiometrics. Somehow, though, the supply has yet to reach the demand as prices keep increasing. Citywide, rental properties are at 94.5 percent occupancy, driving rents up and narrowing renters’ choices.

Millennials are the target market for micro-apartments because they tend to gravitate toward an all-in-one location where they can work, shop and socialize, even if it means giving up space to save a little cash and achieve those desires.

Chicago’s first luxury micro-apartments, FLATS Chicago, began development on seven buildings in Uptown and Edgewater in 2012, converting them into minuscule 275-square-foot-and-up units. There are currently 39 FLATS units available in six of the buildings, starting at $925 for a studio in Uptown’s Bachelor building, 1140 W. Wilson Ave., or reaching as high as $2,200 for a one-bedroom at Libertyville’s brand-new Manchester, 117 N. Lake St. The smallest FLATS studio apartments are under 200 square feet as of January—even smaller than the average Chicago parking space.

A one-bedroom unit at Uptown’s Lawrence House, a FLATS building at 1020 W. Lawrence Ave., costs $1,600 and up while two-bedrooms start at $2,850. Uptown locals can usually find themselves paying $1,200 for one-bedrooms and $1,550 for two-bedrooms, far easier on the wallet than a FLATS rental.

Despite the well-above-average cost, Alex Samoylovich—co-founder and managing partner of Cedar Street, FLATS’s parent company—insisted the buildings are affordable when compared to the larger luxury apartment market.

“If you look at FLATS, yes, it’s a little more expensive than a traditional studio, but you’re talking generic studios,” Samoylovich said. “When you’re comparing luxury properties, you take a studio that’s $1,800 while we’re at $1,200–$1,400. We are the affordable, approachable choice.”

Some of the amenities that Samoylovich said make FLATS apartments worth the price are Lawrence House’s indoor pool, backyard, boxing ring, coffee shop and bar—all located within the property for tenants.

A 138-unit micro-apartment development is also on the way in Logan Square at 2342-48 N. California Ave. that will command $1,200 for a 439-square-foot studio apartment and $1,400 for a 537-square-foot one-bedroom—a heftier price tag than the $1,210 average rent for one-bedrooms in the same neighborhood.

These sorts of developments are more focused on selling their aesthetics—luxury in a small package—than what used to be considered good value for the Chicago market, said AJ LaTrace, editor of Curbed Chicago, an online real estate publication.

“I’ve seen the term thrown around so often: lifestyle development,” LaTrace said. “You’re not renting an apartment—you’re renting a FLATS apartment. Their thing is that, yeah, they’re charging $1,400 per month for rent, but you’re getting a freshly rehabbed apartment [with] high design and other [luxury] amenities. in it as well.”

Samoylovich tried to sum up FLATS’ shtick as he said, “There’s micro-units, and then there’s FLATS.” FLATS renters, he said, are minimalists, the likes of whom “use Uber—they’re trying to not need a car—use Airbnb” and enjoy the image of living in swanky branded apartments.

For some Columbia students, the appeal of micro-apartments is elusive. Darrion Bush, a senior business and entrepreneurship major, currently lives with his parents and is looking for a place to call his own. He said that he would consider a place like the Lawrence House due to its desirable location—but only if it was the cheapest option. If there was a comparably priced non-luxury, non-micro apartment, he said he would likely favor the standard space.

“I’m claustrophobic; I need space,” Bush said. “I don’t want to feel like I’m cramped in a room, so [I would] go with a bigger room.”

Similarly, Katie Caleca, a junior education major who lives in Pilsen, said she wouldn’t be very comfortable living in a micro-apartment unless it was a significant bargain compared to her current $1,300 per month two-bedroom.

“I could stand living in a place that small, but I don’t think I would prefer it,” Caleca said. “It would feel so cluttered and claustrophobic. I understand the trade-off of location and having the amenities, but I think I’d prefer something a little more mainstream, more conventional.”

Those reactions are comparable to those of native Chicagoans. When new luxury co-housing and micro-apartment developments are proposed, local residents’ reactions are typically negative due to the inflated rents, LaTrace said.

“The prices for what you get [in micro-apartments] don’t seem all that reasonable,” said Alby Gallun, senior reporter at Crain’s Chicago Business. “If you look at it on a [price]-per-square-foot basis, it’s probably going to be more expensive [than an average apartment], but on a per-unit basis, the rents will be lower.”

However, LaTrace noted that skeptics often do not realize that the pricier, luxury developments may not be intended for them.

“[Chicagoans] see everything through our ‘Chicago lenses’ so much that we tend to forget that one of the fastest-growing demographics in our city is high-earning young professionals,” LaTrace said.

Young professionals moving to Chicago may come from San Francisco or New York City, where they are already more accustomed to paying exorbitant rates for minimal space, he said. The average one-bedroom rent in NYC is about $2,700, while San Francisco’s average one-bedroom rent is an astronomical $3,402.

“They’re already so used to not having a lot of room,” LaTrace said. “When [out-of-town young professionals] see they can get their own studio for $1,400, to them that’s a steal.”

Samoylovich did not specify the exact demographics of FLATS’ tenants but said its “sociographic” is “people living independent lifestyles [who] live beyond their living room walls.”

Yet some fear that the “pay more for less” ethos of these apartments will change the value proposition for all Chicago renters. The average one-bedroom renter in Chicago already falls short of comfortably making rent, according to a 2015 report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition. The coalition estimated a renter needs to make $17.73 per hour working full time to comfortably afford rent—more than one dollar more per hour than the average tenant’s $16.46 hourly wage.

Chicago’s escalating average rent will continue for at least the next one to two years, meaning renters may be stuck in the same place—for better or worse—until current developments are completed, according to Chris Pezza, director of the Chicago Association of Realtors.

“The tricky part with real estate is [that] supply may take two or three years to come online and finally meet the demand,” Pezza said. “There’s always sort of a lag [until] supply meets demand, and you have pricing equilibrium. It’s certainly not a question of ‘if,’ but ‘when,’ because all real estate is cyclical.”

For millennials who don’t want to live in such tight quarters, the best bet would be to find a trustworthy realtor with citywide connections or simply opt to live with roommates, he added.

The jury is still out as to whether Chicago’s micro-housing boom is just a transient trend or something more permanent. In fact, it’s “the million-dollar question,” LaTrace said.

While it would appear to be little more than a trend currently, Pezza said downscale living quarters will more likely than not continue to be an option for years to come because younger demographics are becoming more and more used to cramming into their homes.

Fortunately for people who still like their space, Gallun said he does not foresee the trend taking over the apartment market as long as rents begin falling in a meaningful way after the new development.

“There is a segment of the market—there is demand for this stuff,” Gallun said. “It’s just a matter of how big [the trend] is. I don’t think it’s going to be a huge thing. It’s never going to represent half or even a quarter of the market.”