Autocorrect a lazy man’s technology?

Reliance on autocorrect may affect spelling abilities

March 31, 2014

As cellphone users become increasingly reliant on autocorrect, engineers are working to make the service more efficient without erasing users’ literacy skills.

Computer scientists view autocorrect as a functionally sophisticated software, according to Piotr Gmytrasiewicz, associate professor in the computer science department at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He said it uses probability distribution and the language model—the probabilities of words being followed by other words—to offer the most appropriate corrections. The software maintains words it interprets as plausible substitutions for writers’ entries, Gmytrasiewicz said.

“Those types of software have access to … whole dictionaries that consist of thousands of words,” Gmytrasiewicz said.

Companies such as Microsoft and Apple are currently working to develop more efficient autocorrect software despite the tediousness of the undertaking, according to Joe Braidwood, chief marketing officer for Swiftkey, a spellcheck software company that works with businesses such as Microsoft and Apple to improve their autocorrect databases.

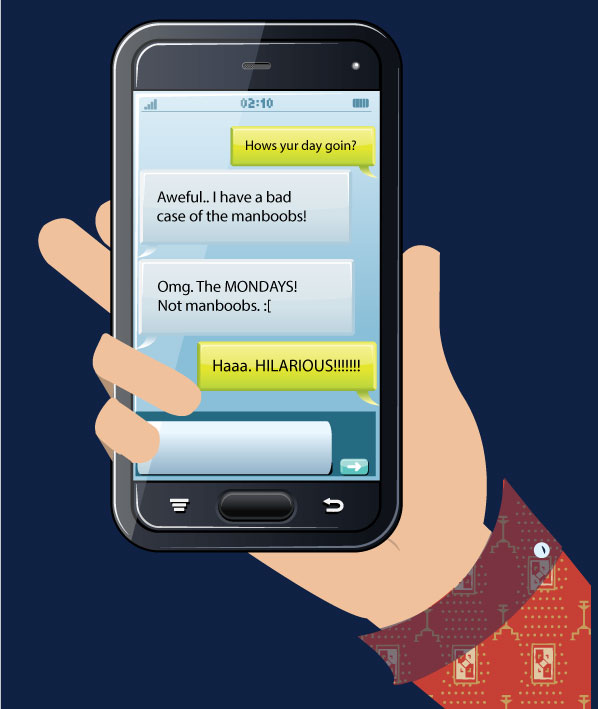

Texting generations are becoming hooked on the technology, which may negatively affect their ability to spell. Reliance on autocorrect begins as soon as the first word is typed, said Dennis Galletta, professor of business administration and director of the doctoral program at the University of Pittsburgh’s Katz Graduate School of Business.

In July 2005, Galletta and a team of researchers measured how over-confidence in spellcheck technology affects a person’s judgment in correcting grammar and spelling mistakes, finding that participants had more errors after editing a document when spellcheck was active than when the software was not used.

Participants were separated into two groups: high verbals, those who scored well on an English language exam, and low verbals, who tested above average on the exam but lower than the other group. Participants were then asked to edit a business letter once using spellcheck and again without it. When the software was active, some correct words and phrases were purposely flagged as errors while actual errors were not flagged. Low verbals performed poorly on both tests. High verbals left few errors when the software was not used, but they performed worse than the low verbals when it was active, Galletta said.

“I think the only thing that we can really say is that they just ignored [the errors],” Galletta said. “If they had looked at them, they would have corrected them. We believe it’s the laziness or the overconfidence in the software.”

Though both groups left errors in the document even when using autocorrect, Galletta said he does not think the technology is necessarily making people less intelligent, but it may have a minor effect on spelling and grammar capabilities. He said typing “LOL,” for example, could cause future generations to forget how to spell “laugh.” He added that younger generations may begin to value understandable communication of language over proper form.

Developing better software using a larger database is still a complex task for engineers, Braidwood said, because language is constantly evolving as people create new slang words and phrases. Understanding and predicting language is one of the hardest problems in improving artificial intelligence, he said.

“That area of research and science is the area we struggle with when building our technology,” Braidwood said. “It’s really complicated, but it’s a significant part of our business.”

Despite the complexity of autocorrect, Swiftkey’s computer scientists developed a technology that better understands the context of working language to improve word prediction and correction by analyzing human interactions and building models of human behavior and linguistics, Braidwood said. The data is integrated into Swiftkey’s software and installed in computers and phones, he said.

Though autocorrect may often receive criticism, Braidwood said he thinks it is becoming less of an issue. He said companies are working to improve their typing technology and overall user experience.

“Companies invest a lot of programmer effort into [the technology] because the best program will be used the most and it translates into the company’s profits,” Gmytrasiewicz said. “These are important products for those companies because they are used so frequently.”